Whiskey & Kansas City: The Story of J. Rieger & Co. Distillery

Sherry-cut whiskey, craft cocktails, distillery tours, tastings

Co-written by Heather Scanlon & Karla Deel

Whiskey in Antiquity Everyone loves whiskey. Whiskey Sours, whiskey ginger, whiskey mixed with muddled fruit. Rye whiskey, Scotch whisky, whiskey made from barley, corn and wheat. Everyone from Mark Twain to Humphrey Bogart to medieval Monks to one of our founding fathers, George Washington, loved whiskey; he kept a successful distillery business in Mount Vernon, Va. Distillation practices date back to ancient Mesopotamia, which eventually evolved into the distillation of whiskey as early as 1405 in Ireland. The word ‘whiskey’ derives from the Gaelic phrase uisce beatha, meaning the water of life. What’s not to love? This water of life has been used to “cure” everything from smallpox to colic, depression, insomnia, and even to the common cold and cough.

War Years and Pre-Prohibition During the Civil War, soldiers took to whiskey not only as a means of solace from the depravity of war, but also as an easily derived anesthetic. This war not only ravaged our soldiers, but also our lands, and harmed civilians and their businesses, including many distillers and distilleries. With legitimate distilleries out of business, black market prices increased from 25 cents a gallon in 1860 to $35 a gallon in 1863. After the war, and into the late 1800s and early 1900s, the United States drank up to 140 million gallons of liquor a year. No surprise, then, that a city on the rise after the war like Kansas City gained the nickname of “Modern Sodom.” According to Kansas City: An American Story, 80 saloons were listed in the city directory for the year 1878 — triple the number of churches and four times the number of schools, colleges, libraries and hospitals combined. To keep up with demand, distillers migrated in from all over the map, to settle in the middle of this country and churn out some libations.

1877 Jacob Rieger established his J. Rieger & Co. distillery at 1512 Genessee in the Livestock Exchange district, present-day West Bottoms—a raucous and rowdy area known then for boozin’ and gamblin’ and dirty dancin’. Densely populated, this high-traffic neighborhood was home to the Union Depot, the innovative and only rail station in Kansas City. The authors of Pendergast! captured the ribald scene:

“The West Bottoms… contained large and prosperous vice interests. Cowboys, travelers, transients, and townspeople provided ready customers for numerous bawdy houses and gambling dens. Well-known madams with glamorous images achieved celebrity status. ‘Hell dances,’ which featured half and totally naked women who mingled through male audiences, took place openly night and day in dance halls. Almost anything was available for a price…Almost every evening, a carnival atmosphere prevailed along the crowded streets.”

Census reports from this time period noted many gunshot wounds occurred in the West Bottoms.

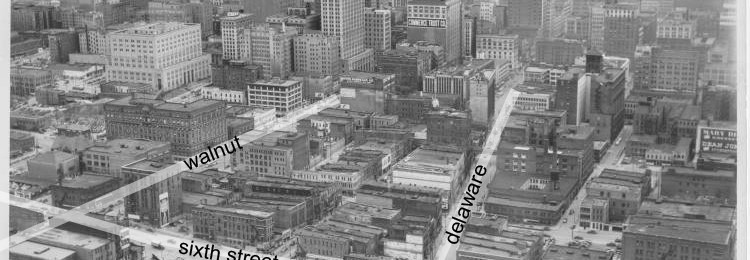

In the late 1880s, Kansas City was home to 200 saloons. That’s about one saloon per every 250 people. Twenty-five of the 200 saloons resided on the Ninth Street block between Genessee Street and State Line — the aptly dubbed “Wettest Block in the World.”

This is where the infamous Pendergast legacy began. James (aka Jim) Pendergast made a big bet at a horse track. His horse raced victoriously, and the winnings allowed him to open his own saloon on St. Louis Avenue in the West Bottoms—calling it Climax, after the winning racehorse. In the late 1890s, a young Thomas Pendergast (aka the Boss Tom, our Prohibition-era city boss) journeyed from the family hometown of St. Louis to work at his brother’s bar.

Tom lived at 1717 W. 9th Street — in the heart of the Wettest Block. It is semi-safe to think that Jacob Rieger and the Pendergast brothers were well acquainted; both families dealt in the liquor business in West Bottoms at the same time.

Rieger & Co. produced gins, wines, rums, cordials, bitters, brandies—and the whiskey! White whiskies, corn whiskies (similar to good ol’ moonshine), malt whiskies. In total, he produced more than 100 varieties of alcoholic beverages. Their most-popular “Rieger’s Monogram” whiskey even boasted a counterpart in Rieger’s Monogram cigar line.

With slogans like “O! So good!” and “Best on Earth,” J. Rieger & Co. backed up the bold claims with a quarter of a million new customers per year. That’s right. 250,000. This was largely achieved in thanks to their ingenious mail-order delivery service, where you might receive four quarts of Monogram whiskey for $3 or eight quarts for $5…right to your door. How convenient!

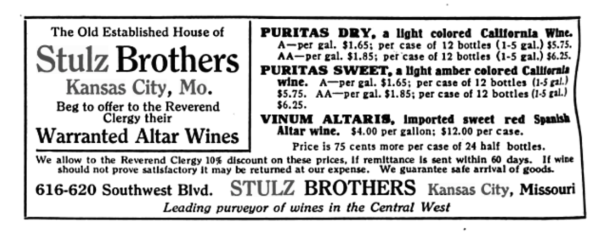

When Jacob Rieger began production of his beloved “Rieger’s Monogram” whiskey it joined at least two other Kansas City distilleries to produce whiskeys with the word Monogram as part of the title. The Stulz Bros. Co., owned by German-born brothers C.S. and E.A. Stulz, produced “S. B. Monogram” whiskey, and claimed that their storage casks could hold up to 375,000 gallons of liquor or wine at a time. They even advertised a discount to clergymen for “warranted altar wines.” The John Spengler Co., who opened in 1869 out of 400 Main St. and then 418 Delaware St. in the present-day River Market, produced the “J. S. Monogram” whiskey, and claimed the title “Oldest Liquor House in Kansas City.” Above all others, though, J. Rieger and his whiskeys rose to become the nation’s largest wholesale mail-order whiskey house.

1881 The “Wettest Block in the World” gained more sizeable patronage as Kansas, whose border was less than a mile from the Rieger operation, outlawed the sale and distribution of liquor statewide. Kansas City, Kansans hopped right over that state border and had their heyday in the Bottoms. The profits earned by the saloons and distilleries on the Missouri side of the West Bottoms in the late 19th century were undoubtedly impressive. Distilleries profited further with the pre-Prohibition tendency of distillers to blend the liquor with some sort of flavoring–anything from sherry to prune juice. This practice of “cutting” the whiskey stretched out the supply at least four times over, and made the hooch flow like the Missouri River.

1899 J Rieger & Co expanded to include 1512-1529 Genessee St. Advertised in the Kansas City Journal: “Whiskey for the grip!” The grip, or grippe, is the flu.

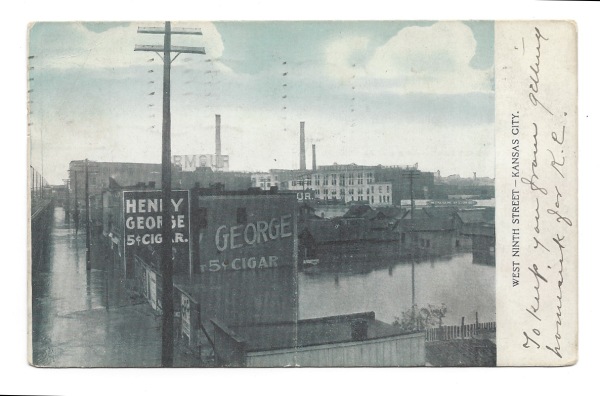

1903 Heavy rains filled the Kansas River, and spilled catastrophically into the bottom lands spanning state lines from Missouri to Kansas. The water devastated the Union Depot, nearly sweeping away the chandeliers from the ceiling. Twenty people died, many found themselves homeless, and businesses in the area sustained severe damage. Just five years later, another flood drenched the bottomland, again threatening the wealth and well being of the businesses, residents and travelers in the West Bottoms.

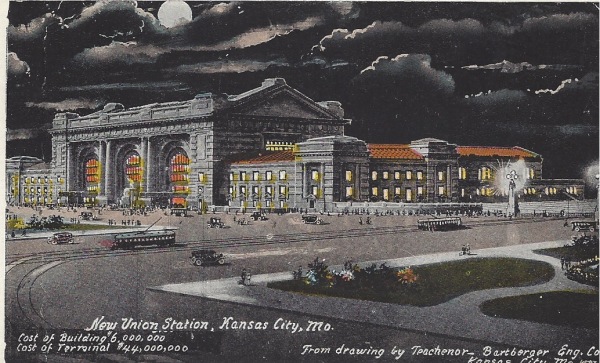

1915 More than staying afloat, Alexander Rieger, son to Jacob Rieger, expanded out of the West Bottoms and opened the Rieger Hotel at 1924 Main St. intentionally near the new Union Station depot (completed in 1914 at Pershing Road and Main Street) in a brilliant branding move for the family name. Anyone passing through the Kansas City heartland might glimpse the enormous bottle of whiskey painted on the side of the brick hotel at 20th and Main Streets.

“[The modern day hotel]”, writes Herbert Weisskamp regarding the Rieger Hotel in his book Hotels: an International Survey, “dates from the early days of railroad travel, when the modest hostelry, prepared to entertain small groups of occasional guests, was forced to become a more commodious and efficient institution to accommodate the great number of traveling salespeople.” Alexander Rieger was a savvy businessman, foreseeing the opportunity the Union Station offered.

And indeed, though mostly patronized by traveling salesmen of the era, the notorious Al Capone often roomed at the Rieger whilst in Kansas City – we imagine Union Station’s proximity made the Rieger a prime spot if the need to flee arose.

The Rieger was sold in 1926, existing as the Travelers Hotel, and rented space to the E. E. Porter Soft Drink Co. During the 1940s, the once-bustling hotel was deserted for a stint until the deed changed hands to Mary Jacobs (circa 1950s). The Milton Hotel and the Acme Decal Co. occupied the space briefly, but the building found a long-time resident in Anderson Photography. Owner Orville Anderson acquired 1924 Main St. in 1962 and rented the upper floors as the Elm Hotel.

1918 J. Rieger & Co. listed as Alexander Rieger Mercantile Co. & Wholesale Liquors. Jacob’s son Alexander oversaw the distillery from the early 1900s on.

Kansas City & Prohibition, 1919 Self-proclaimed “bulldog running along at the feet of Jesus,” hatchet-weilding Carrie Nation, and her comrades who preached the woes of alcohol finally got wishes granted in 1920, when the Volstead Act dried us all out. We went from drinking 140 million gallons of alcohol a year to 14 a year during Prohibition; and we’d be fooling ourselves if we didn’t think Kansas City helped to reach that number.

www.jimmygrist.net

The Rieger’s closed up shop for good in the West Bottoms– by this time, the company had expanded to 1512-1529 Genessee Street. Prohibition was looming, and the Volstead Act that preceded it shut down the distillery.

One can almost perceive the Volstead Act and Prohibition as interchangeable; the ratification of the Volstead “paved the way,” if you will, for the National Prohibition Act and the federal embargo on the production, sale and transport of alcoholic beverages. J Rieger & Co. shut down in December of 1919, just one month before the federal law banning these nationwide went into effect.

Ken Burns, famed filmmaker responsible for Jazz, a History of America’s Music, claims that prohibition never happened in Kansas City thanks to Boss Tom Pendergast. During Prohibition, Pendergast was rumored to have trucks full of frozen chickens delivered to the Savoy Grill downtown, their cavities stuffed with bottles of gin, whisky and rum. The Sugarhouse Syndicate, a mob-run organization that supplied alky cookers with corn syrup during prohibition, helped washtub masters stay in business.

Contrary to belief, whiskey was legitimately available during Prohibition, with a doctor’s note not dissimilar to medical marijuana prescriptions today. The U.S. Government supplied six producers with valid licenses to produce, bottle, and sell medicinal liquors, including whiskeys.

The National Prohibition Act (the 18th amendment to the United States constitution) began as of January 1st, 1920. Fun fact? It banned anything and everything regarding liquor…except for its consumption. The federal government kept a large supply for medicinal needs and religious institutions – for example, Catholic churches use wine as the “blood of Christ” during Communion. Couldn’t step on those religious toes, even though many calling for Prohibition did so from a biblical and immoral argument, most notably, Ms. Nation.

Another proponent for Prohibition was the organization known as the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. From the late 1800s this growing group of women believed liquor to be Satan-derived, and the group acted as a protector for wives whose husbands spent their entire check on booze and would, in turn, often become violent when drunk. This was a time of America’s severe patriarchal tendencies. This was the first time in United States history that women truly had a voice (and used it!) and overcame the stereotype of the female as a weak, inferior creature. Their slogan? “Lips that touch liquor shall never touch ours.”

Though the Prohibition Act, at first, seemed to be a positive institution, in the end, it failed. Miserably. Over time, bootlegging, crime –organized and individual — and death rates from bathtub gin and “jakefoot”—paralysis derived from contaminated Jamaica ginger extract or “Jake”, frequently consumed during Prohibition—ran rampant, and the United States found itself in a much worse predicament than the pre-prohibited era. Prohibition fueled gangsters and mafia families across the country. Al Capone is a famous one – his success in bootlegging liquor and notorious reputation made him a renowned figure and one that desperate people sought to emulate. He also frequented our fine city.

Kansas City was not left out of the scene – in fact, Prohibition didn’t really mean much to the city. Boss Tom kept the liquor a-flowin’ and Kansas City was the hot spot to visit, with plenty of liquor, speakeasies…and police staying out of people’s business. A free-for-all, in those days — earning us our well-merited “Paris of the Plains” nickname.

www.jimmygrist.com

Post-Prohibition, 1933 The 21st Constitutional amendment repealed Prohibition, which had proved utterly disastrous for the state of the country. J. Rieger & Co. unfortunately did not recommence its distillery operations. Rest assured, though. When Missouri hopped on board with the repeal, Kansas City got right back on the horse. Kansans still patronized the Missouri side, as the state of Kansas did not repeal Prohibition until 1948.

1950 The old J. Rieger distillery on Genesee was razed. Today, in its place, stands the newly constructed residential community, the Stockyards Place.

2010 Thanks to local restaurateur and one of Kansas City’s most beloved mixologists, Ryan Maybee, the Rieger Hotel Grill & Exchange opened, renewing the life of the Prohibition-era hotel ran by J. Rieger’s son, Alexander. In the basement of the Rieger, you’ll find Manifesto, a dimly lit, self-proclaimed neighborhood bar and cocktail-liberator, a further vision of Maybee. Here, you’ll find drinks that tip a hat to our bad-boy days: everything from the rye-based cocktail, “Jackson Co. Democratic Club,”to the Ward & Precinct” and even, “The Pendergast.”

2014 Harnessing the ingenuity and hard work of whiskey distiller Jacob Rieger, Ryan Maybee and Andy Rieger—direct descendent—embody the spirit of Kansas City’s past with the (re)launch of J. Rieger & Co. Whiskey. Ingredients include corn, malt and straight rye whiskey, “cut” with the 15-year-old Spanish sherry, Olaroso. The inclusion of the popular pre-Prohibition practice of “cutting” flavors into whiskey ensures the legacy of this new take on an old style of Kansas City whiskey.

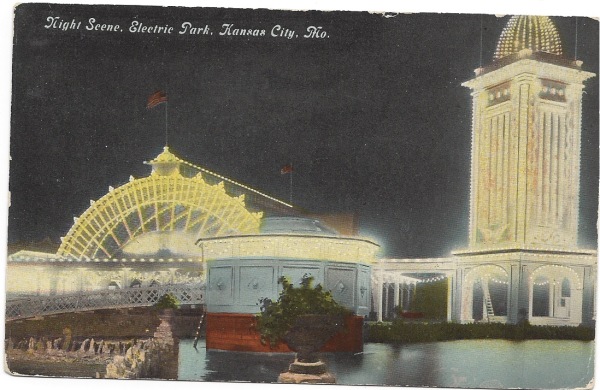

You can find the present-day J. Rieger & Co. distillery in the East Bottoms, in the old bottling house of Heim Brothers Brewery. The Heim Brothers Brewery (also known as Ferd Heim Brewery) was founded in 1887 by Heim brothers Ferdinand Jr., Michael and Joseph. By the early 1900s, these boys claimed the title of the largest brewery in the world, and also opened the first (and second) electric amusement park in Kansas City, forerunner of our modern theme and amusement parks, like Worlds of Fun. It is said that a young Walt Disney found some real inspiration in these parks. As a national prohibition was stewing, the Heim brothers (like J. Rieger & Co and so many others) promoted their product as a beneficial health tonic–“derived from perfect hops, imparts vigor to the system, aiding the tired brain and strengthening the nerves.”

But like so many others, the Volstead Act and the 18th amendment claimed the Heim’s brewery–and Electric Park. With no capital, the brothers were unable to rehab the second Electric Park after a fire rendered much of it unusable and dangerous. Unfortunately, the East Bottoms brewery was razed in the 1890s, making way for a horse carriage manufacturer. The bottling house remains, repurposed now by J. Rieger Whiskey Co., continuing the long history of booze in Kansas City.

Thirsty days hath September,

April, June and November;

All the rest are thirsty, too;

And what’s a thirsty (wo)man to do?

Drink J. Rieger’s Whiskey! Salut!

To purchase J. Rieger & Co.’s Kansas City Whiskey, shop here: