Stitching the North Loop Back Together

urban renewal, north loop, failed interstate development, restoring urban density, River Market, Columbus Park, downtown, Interstate 70, downtown loop

As Kansas City dusts off decades of disuse and slowly reinvigorates various corners of its 320 square miles, it may be wise to remember how we utilized the city in the past. We can easily recall the beauty of certain boulevards, the sublime decay of old tax ID photos and the majesty of grand civic monuments. But what makes a city truly great is its usefulness. As our city leaders continue to refashion and modernize this fountain-soaked burg, we can look to our extant framework for inspiration as we remake what it will be in the future. I’d like to demonstrate how lost density from (failed) interstate developments is entirely possible to reclaim today. What better place to start than the beginning; Kansas City’s own angular intersection of social and economic transience, worn as a deep laceration known presently as the North Loop.

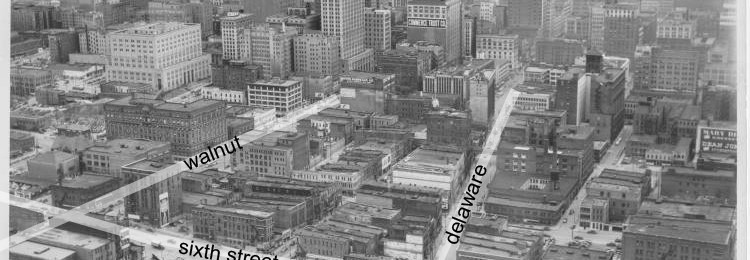

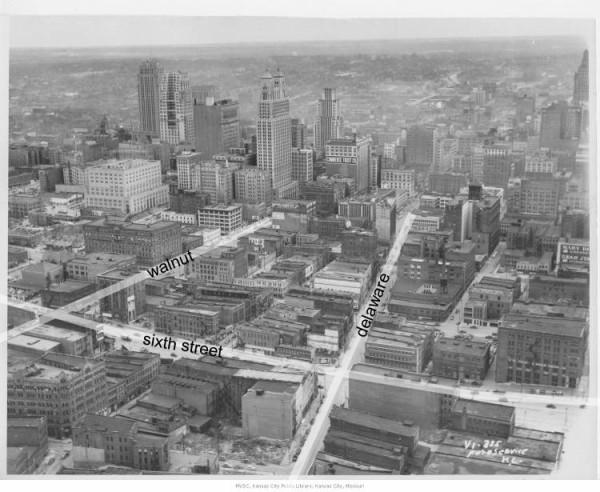

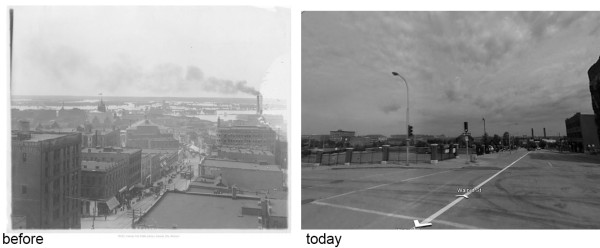

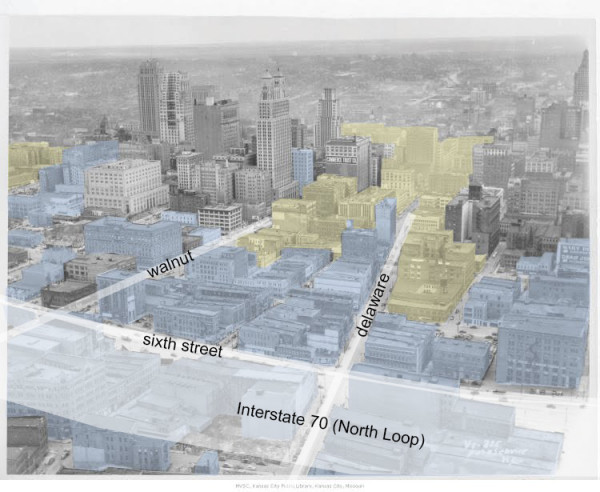

The North Loop is the none-too-sexy moniker of Interstate 70 as it traverses the north side of downtown Kansas City, paralleling what is nominally known as Sixth Street. At one time this land unified the disparate, angular grid of two distinct areas and tied together the diverging economic interests of an original river town and its burgeoning business districts to the south. Now referred to as the River Market, the area south of the Missouri River and north of Interstate 70 was originally platted as ‘Kansas’, and then incorporated as the Town of Kansas, after the Kansa tribe who the early French settlers met upon settling the area. In later maps of the 19th century this area is referred to as the North End, Old Town, and Little Italy, before the interstate highway system separated and isolated Columbus Park to the east in the 1950s, effectively cutting off most of the residential population from the business center and separating the ubiquitous river-oriented street grid into two disconnected neighborhoods.

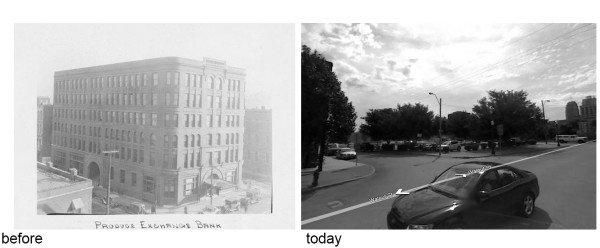

While many remaining warehouses and late 19th-century buildings have recently been converted into apartments, restaurants, and businesses, the southern edge of the River Market has remained a void of reoriented streets and parking lots. Tragically, some of the demolition in this area occurred well after the completion of the North Loop in the late 1950s, with the demolition of the Produce Exchange in the 1980s as a prime example. Nominated for the National Register of Historic Places in 1984, this six-story building is now the site of a small surface parking lot at the southeast corner of Missouri Avenue and Walnut. Originally built in 1892 as the Temple Block Building, both the Traders Bank and the Produce Exchange Bank were located here in the early 20th century. By 1957 the Produce Exchange Bank merged with and became known as Merchants Bank, and remained at this location until 1977.

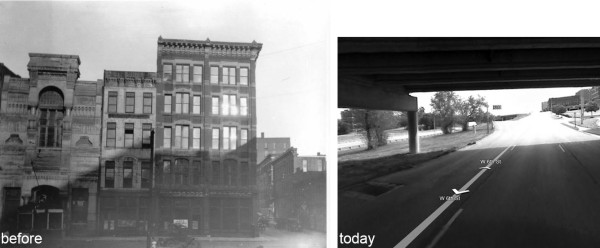

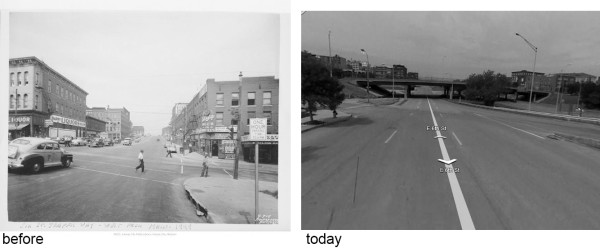

Beyond the lively bounds of the River Market, south of the scruffy undefined edge, lies the massive two-block wide stretch of the North Loop (Interstate 70). Much of the singular identity of this area, and the organic way it tied into the larger downtown area, was removed in large swaths during the 1950s. What remains is a vast, empty expanse of highways, onramps, and unkempt medians. Directly to the south of this begins the stretch of surface parking lots that girdle the Central Business District. Most of this area, pre-1950, was home to very large buildings and a dense street grid, but by World War II the area was considered destitute and undesirable. Many of the city’s social services were located here at the time, including the City Union Mission and various shelters and homes, alongside some of the morally questionable uses that excite Kansas Citians to this day. Shiny glass buildings and autobahn-like limited-access highways were seen as the future of development, and conveniently, a way to socially reconstruct the city. Many residents were displaced from these buildings, and many businesses were relocated. This extensive social upheaval had far reaching effects. Our city was once intact. The vast amount of infrastructure and space that was removed in such a short amount of time facilitates what we can recognize today as a failed social experiment.

These mostly empty spaces and a handful of buildings remain south of Sixth Street and north of Eighth, and serve as a reminder of the limited vision of past leaders who did not see past a contemporary urge to reorganize depressed social areas. The site of buildings such as the large New Nelson Building, at the southeast corner of Main and Missouri, is now an off-ramp and grassy median. The collection of buildings around the Junction, including the Westgate Hotel, the American Bank Building, the Alamo Building, and the Manhattan Building, among others, is now a widened and elevated stretch of Main Street from Seventh to Ninth. The collateral damage after the North Loop construction affected the Midland Hotel (formerly the Railway Exchange Building) at Seventh and Walnut, the Walsix Building at Sixth and Walnut, and the previously mentioned Produce Exchange Bank, which all were demolished for surface parking after the completion of the highway. I don’t have room here to show you photos of every building mentioned, and the ones mentioned are a fraction of the total removed.

I look at these multiple, flat blocks of land and see not only the dense structures that used to proliferate, but also the countless jobs and homes that were held within their confines. How many lives were so quickly altered to accommodate this massive project? It is true, in the 1950s most planners thought that Urban Renewal, or the removal of pre-war neighborhoods with mixed ethnicities, underperforming tax revenues, and non-modern buildings, was essential to not only accommodate the automobile but to also encourage modern developments. What we are mostly left with is a poorly performing highway segment and many acres of undevelopable land.

The only useful thing that came from this is the highway, and that is debatable. The North Loop fails as an interstate highway and is redundant when coupled with I-670 to the south. The area would be better served by a parkway solution that restores private land, provides for local access to downtown from the rest of the interstate system, and allows for some restored density. Just recently this essential idea has been openly discussed by local leaders, and it deserves the full attention of our community. We should be aware of the massive scale of removal suffered in Kansas City in the name of progress, and the social repercussions these failed experiments have had.

However, I’m not here to argue about the highway system, or to look over my shoulder and complain about past mistakes (well, maybe a little). Once you place yourself in these empty spaces and imagine the densities of the past, it isn’t too difficult to realize an alternative to the current North Loop. The area is large enough to sustain a thoughtful stitching together of the broken fabric between downtown and the River Market, while still accommodating a parkway to shift vehicles from the remaining limited-access highway to the local streets in the area. Remaking the transportation connections in this area would free up many acres for development and parks; reinstating just half of the lost density would accommodate thousands of residents and workers. Too often we approach Kansas City’s awakening in a piecemeal fashion; here is an opportunity for a thoughtful, dynamic solution. As the public discourse continues on this topic, I hope to explore many other lost corners of the city and to illuminate their past, and ultimately their endless potential.