The Kansas City Feminist Who Made June Cleaver

Kansas City Garment District, Women in the Workplace, Nell Donnelly, Fashion, Feminism, June Cleaver, 1950s Pop Culture, B-25 Bomber Factory

Google “June Cleaver.” Instead of images of the timeless character from the Leave It To Beaver television series portrayed by actress Barabara Billingsley, you’ll find pictures of brightly colored dresses. The show is an archive of an era of polished domesticity, with June Cleaver’s clothing characterizing the feminine archetype associated with the traditional gender roles and family values of midcentury America.

Advertisements in newspapers during this time confirm this with overwhelming evidence. Be beautiful. Be charming. And don’t burn dinner! Nearly every household product in some way bears the mark of a meticulously groomed domestic woman with a tiny waist as its proprietor.

The presumption of woman’s singular role as housewife during the era of June Cleaver was later called into question by feminists of the next generation. Now the images of her waiting at the door for her husband in a lovely, feminine dress symbolize a time of restricted roles for women. But society’s former picture of the American woman –the one before the radiant, slight-waisted wife in heels and gingham—is lesser known. If it were, perhaps it would be said that, when it comes to June Cleaver, we’ve got it all wrong.

American homes prior to the late 1800’s lacked nearly all of today’s amenities. Washing clothing, fetching water, and keeping the filth minimal made notions of beauty while performing these tasks laughable. But the turn of the century saw a series of improvements: cars instead of horses, streets paved instead of dirt, and electric appliances instead of elbow grease. Yet even as household conveniences increased, fashion in the day-to-day life of a housewife remained stagnant. If a woman wanted a more flattering item of clothing, she’d go to a tailor for a custom-made dress. That was expensive. A 1914 ad for a tailor in The Pantagraph, an Illinois newspaper, suggests that $15 dollars was a pretty good deal. Conversely, the accepted daily look could be purchased at a dry goods store for about 65 cents—shapeless, cheap frocks made with only the most practical of considerations.

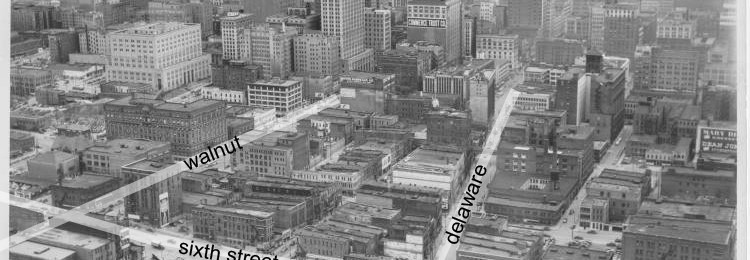

In 1916, a young Kansas City wife named Ellen “Nell” Donnelly Reed rejected the tradition of the lackluster housedress, and elected to make her own in protest. In a clever act of enterprise, she also set out to sell copies of her first frock at the newly built George Peck Dry Goods Store at 1044 Main Street in downtown Kansas City, Mo. Her dresses were fashionable, figure-flattering and could be purchased for the competitive price of one dollar. Not surprisingly, Donnelly’s creations quickly disappeared from the racks at Peck Dry Goods. By the time her husband, Paul, returned three years later from fighting in World War I, Donnelly had a legitimate business with 18 people on her payroll and $250,000 in revenue.

Even as the Great Depression was at its height, Donnelly gained iconic status internationally as the persona “Nelly Don.” She employed 1,000 Kansas City people to produce affordable dresses that lent dignity to women in their roles as housewives, promoting them to a higher status in society. Women all over the country began to clothe themselves in a way that accentuated their natural beauty even during the workweek. An estimated one in seven women wore Nelly Don dresses. A style revolution ensued, and the face of the American housewife was transformed. Incidentally, Donnelly herself had become a millionaire.

Donnelly’s enterprise was not just unusual because of her passion to celebrate the American woman through fashion. She was also an example of fierce female independence and business savvy. As her business continued to thrive, reaching millions in revenue each year, Americans continued to face hardships with the onset of World War II. Many women entered the workforce for the first time in their lives, taking on jobs that no American woman had taken on before—welding and sheet metal work, for example. Much of this work took place in factories built to make fighter planes and other war accessories.

The United States National Defense Advisory Committee determined that one of these factories would be constructed in Kansas City, at the Fairfax Airport. The new B-25 bomber plant was established just under five miles from the Donnelly Garment Company. Donelley’s factories offered support for women in the workplace by continuing to provide women with comfortable and flattering clothing made for their bodies. The Donnelly Garment Company produced factory garb for the “Rosies,” and became the largest manufacturer for women’s work clothing as well as uniforms for women who served overseas.

In the decades that followed after the war, the Donnelly Garment Company became the largest dress manufacturer in the world. Even with such growth, the Kansas City business continued to profit both the customers and the women working for the company. Employee benefits comprised many unusual perks, including tuition for women interested in continuing their education. Donnelly even helped provide college funds for children of her employees, ensuring another generation of self-sufficient women could enter the workplace prepared to succeed alongside their male counterparts.

Donnelly’s dresses may have donned a generation of domesticated women, but her enterprise championed a woman’s right to shape her own identity, beginning with clothing— but certainly not ending there. June Cleaver’s dresses were a direct product of a movement that made a significant stride in equality for women.