Mary Colter: Madame Architect Extraordinaire

Mary Elizabeth Jane Colter was an architect ahead of her time. One of her masterpieces included portions of the interior layout of Kansas City’s own Union Station. Her work can also be found in several parts of the United States, especially in the Southwest and along the rims of the Grand Canyon. Colter had a prolific career, in part because of her rare approach to design and in part due to her hardy demeanor. She excelled while working in a field with almost exclusively male counterparts.

Born in 1869 in gritty Pittsburgh, Penn., Colter lived there with her parents until she was seven. After that, the family moved to St. Paul, Minn. When her father died, Colter began to help with the family finances. She begged her mother for permission to attend California School of Design in San Francisco and study architecture. Colter graduated the school in 1890, joining only 22 other female architects in the country at the time.

Colter began with a job outside of her ideal role as a lead architect and taught high school for nearly fifteen years. Her fate changed in 1901 during a visit to a friend in San Francisco. The friend worked in a gift shop owned by the Fred Harvey Company, a hotel chain with 83 different businesses along the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe railway. The railway stretched from Kansas City to California. Fred Harvey House restaurants were said to bring “clean living, chastity and clean tablecloths to the rough-tough towns of the pioneer Southwest.” Colter’s connection to the Harvey company led to an opportunity to work on a small interior design project that Harvey’s daughter, Mary Harvey Huckel, handled for his business.

Colter didn’t disappoint Harvey with her unique flair and abilities. Already a champion of women in the workplace, Harvey made his mark as the first known American business owner to hire women to serve food in restaurants. These women became known as “The Harvey Girls,” said to have helped transform the rough-cut Southwest. Harvey also gave Colter a job, not as a Harvey Girl, but as one of the first female architects in the country.

Described as a somewhat cult-like figure with a reputation for being rough around the edges, Colter would smoke packs of cigarettes in a single day, curse and drink without restraint, and work meticulously to bring her vision to life. She became a major asset to Harvey’s business. Though technically an employee of the Kansas City office, she traveled frequently to work on assignments around the country.

A series of structures for Harvey around the rim of the Grand Canyon became Colter’s most well-known project. She used Native American art and architecture for her inspiration. She commissioned a group of Native Americans to help with the project in hopes that it would look and feel authentic. She spent a great deal of time and money making the interiors of the hotels feel much older than they were. She even created imaginary histories for some of the buildings she designed, giving visitors the feeling that they were stepping back in time into history in all aspects of their experience.

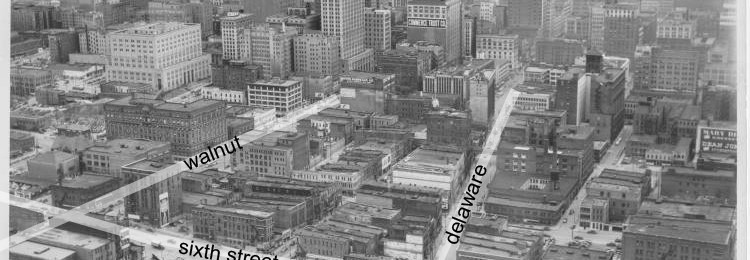

Although Colter’s work for Fred Harvey’s enterprise took her far from her base in Kansas City, she did leave her mark here. The booming Fred Harvey Co. was an essential cog in the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad machine. Many of the railroad stations’ (or towns to which they belonged) only existing restaurant was a Harvey House. As the original location for the Harvey operation, Kansas City’s Union Station housed the full array of Fred Harvey’s businesses: coffee shop, restaurant, commissary, gift shops and newsstands. Colter designed the interior of Harvey’s Restaurant and Westport Room.

The restaurant was reputed as a bright space, with sparkling glass windows, white linens, and fine china. Men were required to wear a coat. Former employee Gloria Kaufman reminisced that her experience there as a Harvey Girl during the 40’s was exciting, even if it was the hardest work she would ever do.“It was important to be chosen to help serve the meal because important Kansas City business men ate there,” she said, “and the tips were always good.” She also said that celebrities and troops were a common occurrence, and the chance to visit with the soldiers was one of the best perks of the job.

Like so many of her projects, Colter’s work in Union Station can no longer be seen. But recent efforts are being made to preserve Colter’s remaining designs. Some of the Grand Canyon buildings are still standing today and are currently in use. Kansas City’s Union Station has joined the effort, and now has a display outside the former Harvey House Restaurant featuring the original china and a painting of the restaurant during its heyday.