The Fall of the Epperson House

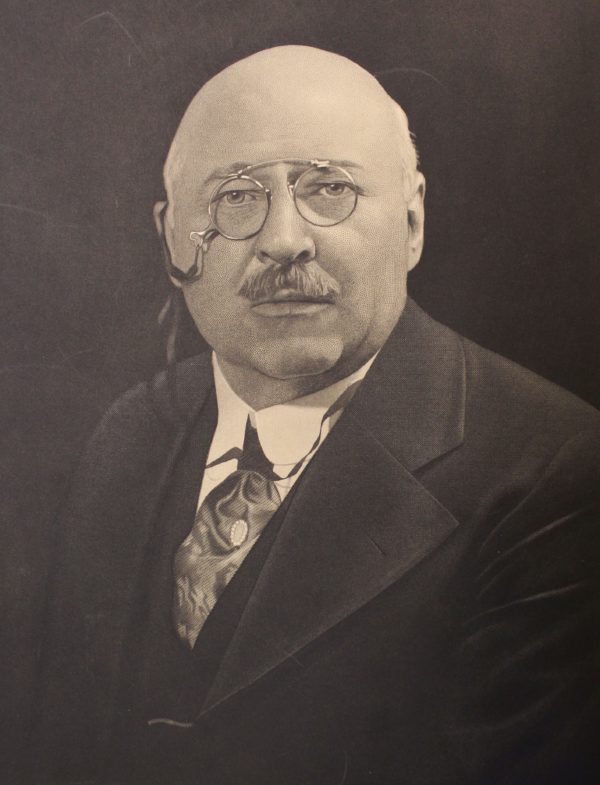

Uriah Spray Epperson died in 1925, leaving his baronial Tudor-Gothic mansion at 52nd and Cherry Streets in Kansas City, Mo., to his wife, Mary Elizabeth. After all, he had built the place with her in mind. It was then known to them, and Kansas City society, as Hawthorn Hall. Only much later in time would it come to be called Epperson House. When U. S. Epperson first began to envision the scope of the home that his newfound wealth could create, he devised an imaginative version of the finest English country home, encompassing a range of architectural styles.

The house’s construction would last from 1919 to 1923, during which the most skilled craftsmen available carved intricate designs into the massive oak fireplaces, balustrades and wall panels. Plasterers created rococo crown moldings and ceiling décor. Masons, marble cutters, stained-glass artisans and laborers of every measure assembled an edifice on the four and a half acres of a wooded hill worthy of any old-world monarch. Part status symbol, part testament to Midwestern resoluteness and stubbornness, the Epperson House was meant to stand in lasting remembrance of a man that grew from poverty to wealth in Kansas City and always considered it to be his hometown.

Mr. Epperson became a prosperous businessman and philanthropist who was an underwriter of fire insurance for grain elevators and lumberyards. But he had come to Kansas City from Indiana as a boy in an aging covered wagon, filled with his family and all their earthly goods. His father was risking what money he had left to become a partner in a meat-packing plant in the growing stockyards of Kansas City. His Quaker roots instilled in him the value of hard work at a young age. He quickly worked his way from the filth and gore of his father’s packinghouse to the gleaming halls of commerce and finance. So, when the time came for him to construct a mansion that would reflect his wealth and status, he hired the renowned French architect Horace LaPierre to help plan and oversee the construction. After nearly five years of work, the project had cost over $450,000 in 1923, or $6,300,000 by today’s standards.

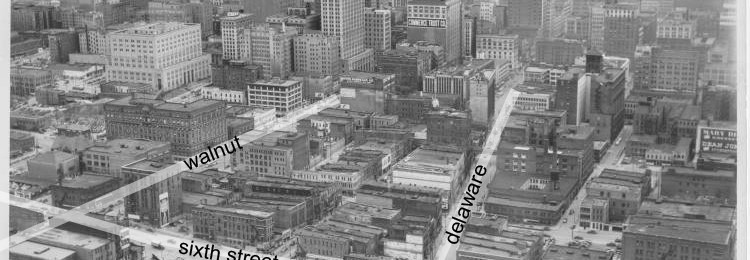

Mr. Epperson had been the director of the Commercial Club in 1897, the forerunner of the city’s Chamber of Commerce, serving as vice president and president for several years. He became a director in the Commerce Trust Company, which later became what is still operating as Commerce Bank. He was a director of the Convention Hall Association for about ten years, and, as its president, helped materially in pushing to successful completion the rebuilding in 90 days of the first hall, burned after Kansas City had been awarded the National Democratic Convention of 1900. He was long associated with the Priests of Pallas, the fall festivities association inaugurated by the businessmen of Kansas City. But throughout the city he was best known for creating the Epperson Megaphone Minstrels. It was a group of the city’s finest musicians who assembled for annual concerts to raise money for many civic improvements, including the creation of free public baths.

Epperson was a member of most of the city’s prominent country clubs as well as the Chicago Yacht Club, and South Shore Country Club, the Atlantic City Yacht Club as well as the Lambs’ Club, of New York City. Mr. Epperson enjoyed many activities, but his favorite was his fascination with “motoring.” He formed the K.C. Automobile Club, since he owned the first automobile in Kansas City.

But as his wealth and influence grew, so did his health begin to decline. His absences from board meetings and social events became more and more frequent. As construction of his monumental residence wore on he continued to oversee every detail and refused to allow anything short of perfection. Only four years after the house’s completion, Uriah died in his home of a cerebral hemorrhage. At the time, according to the newspaper headlines, much of the city mourned, and it was said that he died much beloved and without a hint of scandal.

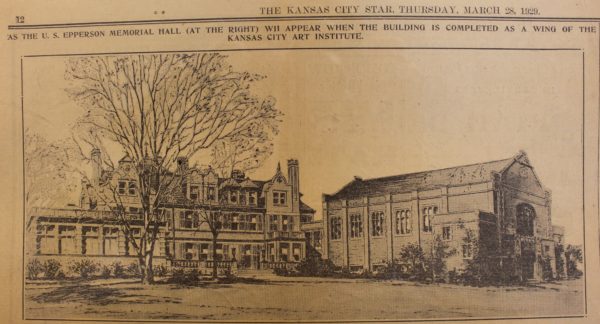

Although Mary Elizabeth was not born in Kansas City, having also come there as a child, she had always known wealth and comfort. She was a Weaver—of the prominent New York Weavers, whose roots extended far back into Welsh and European aristocracy. But she had a passion for civic duties and partnered with her husband in contributing to their adopted city and its public good. For a time, she was the greatest contributor to the Kansas City Philharmonic. She loved painting and painters and was fondly acquainted with El Grecco, Filippo Lippi, Le Brun and Van Rijn. It was said that she gave because she loved, and she loved unto the end – and beyond. She made a substantial bequest to the Kansas City Art Institute, funding an auditorium and display space, named the U. S. Epperson Hall and Memorial Arch.

Mrs. Epperson lived in Hawthorn Hall until her death in 1939. Having no children or other close relatives, Uriah’s closest business associate, James Jesse Lynn had been bequeathed ownership of the house and the Epperson estate. Lynn intended to use the house’s many rooms as offices for the Epperson Underwriting Company, but other wealthy neighbors objected such a use. In September 1942, he instead donated it to the University of Kansas City.

Before the university could agree on a suitable use for the extensive mansion, the wartime needs of the country offered a temporary and patriotic solution. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941, many Missouri and Kansas facilities were needed for United States Army Air Force (USAAF) training posts. In September 1942, the university renamed it the Epperson House Resident Hall for Men and opened its doors to house forty-four aviation cadets. To accommodate the cadets, steel cots were arranged in rooms that once held imported baroque furniture. Instead of musical concerts and theatrical readings, the Great Hall became a place of instruction in aeronautical knowledge, navigational routines, and flight procedures.

After the war, the university reclaimed the mansion in earnest and began what would become nearly continual modifications to its interior to accommodate classrooms, offices and storage needs. Over the years, the house was used as by the School of Education, Conservatory of Music and lastly, ironically, to house the Department of Architecture, Urban Planning and Design.

Despite being one of the finest examples of Tudor-Gothic architecture in the region, the house has remained unprotected by any regulatory historical registers. Although the Historic Kansas City Foundation has kept the structure among its list of Endangered Places for many years, the group has no actual restrictive powers over the house’s continued neglect.

Little did anyone at the time know that by donating the house to a public university it would be dooming the magnificent mansion to an untimely, slow but certain demise. Although several large mansions built by Kansas City’s elite were also donated to the young, struggling university around the same time, they were more adaptable to the needs of the students and faculty, albeit at considerable cost. Converting large family homes into classrooms, offices and other public spaces certainly required extensive modifications. But the very features that made Epperson House first stand out as a local architectural wonder have prevented it from being easily adapted into modern pedestrian uses and needs.

In order to support a large classroom, wooden planking covered the beautiful Grecian-tiled swimming pool in the basement. The two elevators had their cables severed and their shafts covered over and converted into storage closets. Still more “improvements” were made that removed many of the unique and opulent features that once made up so much of the house’s character. The grand open-air West Porch, which once overlooked a pastoral landscape, was walled in to create an administrative office suite. The thick, studded oak front doors that once welcomed William Rockhill Nelson, J. C. Nichols, Robert Long and other luminaries were replaced by gray, utilitarian slabs. Imported brass lighting fixtures were replaced by track lights and modern efficient lighting systems. But the most damning of all the modifications was what was inflicted to the massive, distinctive tower that once loomed high above the structure. The crenellations were unceremoniously torn way, essentially beheading the once grand mansion. It was claimed that the crenellations were “falling down,” although it’s unclear just why such an egregious measure in the name of safety was undertaken, especially since the plans were already in the works to shut the entire building down. While the mansion is over ninety years old, it is a common enough age among other more renowned, but well-maintained residences and buildings in the area.

While the many modifications and attempts at modernization that have changed so much of the mansion’s original charm and character, some have also caused extensive damage and loss. During the installation of central air unit, a worker soldering pipes in the attic set fire to the insulation causing the sprinkler system to erupt. The water did tremendous damage to the library and woodwork.

The continual affronts to the house’s appearance have only perpetuated long-held rumors of the place being haunted. Its Gothic appearance, vast size, warren of hallways, stairways and suites, has inspired many ghostly tales of tragedy and even murder. It was featured on the television series “Unsolved Mysteries” as one of the top five haunted houses in the United States. And in the 1980s the house’s dark facade and a long tracking shot of the front concrete stairway were used in the opening of television Channel 41’s Creature Feature, as the home of the show’s host, “Crematia Mortem.”

A spectral “lady in white” is said to roam the halls. The smell of cigar smoke has often been detected in the Great Hall. And the sounds of screams and organ music occasional waft through empty halls. Since the house’s closure in 2014, it has certainly become a ghostly shell of its former grandeur and position within Kansas City society and culture. It is a place where history and progress have collided, and for the moment, progressiveness is winning a Pyrrhic victory.

Exactly why such a historical and unique edifice as Epperson House now sits empty and neglected is a frustratingly simply mix of economics and an unrestrained attempt to legislate what is in many respects a matter of civil rights. The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 is a federal civil rights law, established during the George H.W. Bush Administration, which entitles people with disabilities access to public buildings. It requires public buildings to have wheelchair ramps, elevators and bathrooms equipped with special handrails for the disabled. The winding stairways recessed floors and other level changes throughout Epperson House violate most of the law’s conditions for ADC compliance. One estimate to renovate Epperson House merely to comply with current ADA standards was a minimum of $1 million.

Another much more banal reason that the house has been sentenced to a bleak and uncertain future is because of “weatherproofing.” Epperson House still retains most of its original leaded and stained-glass windows. Heating and cooling to maintain a uniform comfort level throughout seems no longer to be manageable. The fireplaces that were originally planned to help with heating the many rooms have been long sealed. It is estimated that the university spends about $60,000 each year heating and cooling the aging structure, as well as repairing leaks and fixing broken windows. Estimates to completely restore and ensure full public accessibility to the house range from $8 to $10 million. It’s a cost that the public university is simply unwilling and unable to justify. Without finding a benefactor to spend upwards of $10 million toward the necessary renovations, the mansion will continue to deteriorate, mostly forgotten by the city that once, symbolically, built it.

In the 1920s, as construction wore on, Mary Epperson took to referring to the massive and costly undertaking as Epperson’s Folly. Still, she was enchanted by the sheer spectacle of it all. She had a passion for the trees and foliage on the land and fought to keep as many trees as possible undisturbed. She was especially fond of the Hawthorn trees. The hawthorn is a small, prolific tree that produces an attractive and fragrant white bloom.

In a profound acknowledgment of the Epperson’s amassed wealth and influence in the region at the time, and perhaps just as a concession for Elizabeth’s patience, in 1923, the state’s legislature designated the white hawthorn blossom to be the official state flower of Missouri.

On October 26, 1939, over 600 people crowded into Hawthorne Hall, along with the entire Kansas City Philharmonic, for Mary Elizabeth Weaver Epperson’s funeral. Family, friends and dignitaries gathered together—hushed and reverent. Her casket rested on the Great Hall stage, surrounded with floral wreaths and sprays. An account of her funeral read, “On her hillside were the trees she loved, and they seemed to bow their heads in melancholy expectancy. Within her great Tudor house was a mountain of articulate bloom.” Many of which were bouquets of white hawthorn blooms.

The director of the Philharmonic, Hans Holzer, raised his baton and led the somber playing of the Largo from Handel’s opera Serse (Xerxes), a favorite piece of both Mr. and Mrs. Epperson. Then Bishop Robert Nelson Spencer read the benediction. A written account of the ceremony concluded with, “The last song had been sung; the last prayer had been said; the last tribute had been paid; the ceremony was ended. The friends, still silent and reverent, filtered out of the great house and merged into the busy world, and the gentle benefactress merged into history.”

Mr. and Mrs. Epperson have long passed away into history and, for now, it seems that their once glorious home is doomed to follow them there. In the end, Epperson’s Folly was to have entrusted his creation to an uncertain future within the city he once helped build. UMKC is simply unwilling and unable to restore Epperson House for any possible use. And, the school refuses to sell the property—not that there is a willing buyer able to take on its current disrepair. It is unlikely that the City of Kansas City or the State of Missouri will provide the funds needed to save the structure. So, it must be up to those of us who care about the past and future of Hawthorn Hall to find an amenable solution before another piece of our city’s history falls to a wrecking ball.