Tour Through Hell’s Half-Acre

West Bottoms, Hannibal Bridge, immigration, Wettest Block in the World, exodusters, Arthur Stillwell

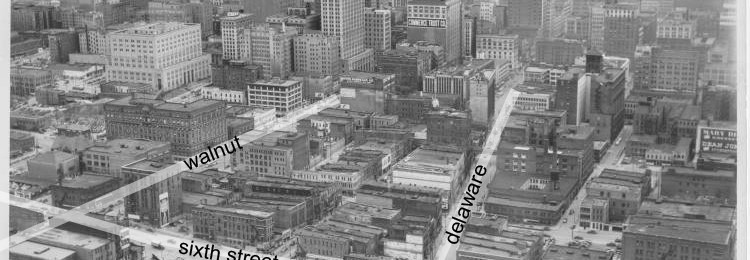

Oh, the good ol’ West Bottoms. Kansas City, Mo.’s original downtown housed the Union Depot, meat-packing plants, warehouses, one helluva rowdy crowd in its numerous saloons and brothels, and the infamous Hell’s Half-Acre. Originally settled in the late 1860s by black workers busy building the Hannibal Bridge, Hell’s Half-Acre would, by the 1880s, span the entire area north from Ninth Street to the very banks of the Missouri River (or, essentially, the bluffs to the river).

Image courtesy of Miller Nichols Library, UMKC University Libraries

An area such as this is known as an enclave, which by definition means: “a portion of territory within or surrounded by a larger territory whose inhabitants are culturally or ethnically distinct.” And in Hell‘s Half-Acre, it began with the African-American migration northward – newly freed slaves moved in masses to Kansas, the Free-State.

Many arrived via steamboat into Kansas City with the intention of heading further north. Out of money or ill and unable to continue northward, some of these Exodusters became so by accident. These new Kansas Citians needed shelter, which they found in shacks and shanties.

Rather quickly, however, Hell’s Half-Acre filled with white immigrants, mostly German, Italian and Irish. The housing was cheap. It also attracted the ne’er-do-wells already working and residing in Kansas City, though here and there one might find an “upstanding” citizen with a white collar job sprinkling the ethnic melting pot of the enclave. By the 1900s, whites outnumbered blacks in Hell’s Half-Acre two to one.

These changes prompted black families – and the Irish, German and Italian — to move out of the neighborhood as quickly as they were able. Hooligans and criminals and prostitutes (the West Bottoms was quite notorious for bad behavior) drove out good people trying to earn a living. The 1900 census reports 535 black residents occupying 108 “homes.” Interestingly, it reports 1,094 white residents occupying just 136 households, averaging eight people to a shanty. And that’s an average – many housed more than eight, to be sure.

Another reason for families to attempt escape from Hell was disease. With that many people in such close quarters, diseases and nuisances such as lice or bedbugs might spread rapidly. See, one of the main reasons the enclave merited the name Hell lie in the fact that there was no clean water available. There was no sanitation of any kind. It was a filthy slum of poverty, delinquency and dreadful living conditions.

One saving grace within Hell was one Arthur Stillwell, founder of the Kansas City Southern Railway and entrepreneur who apportioned $40,000 to build the Bethlehem Night School in the enclave. This sanctuary house provided for mothers and children residing in Hell’s Half Acre, offering education, aid and oftentimes clothing for poor families.

Luckily, the Hell’s Half-Acre nickname – not exactly a positive one – didn’t remain a permanent moniker for the city. She reclaimed the Kansas City name as the town developed and grew into a major crossroads for business, railroads, meat-packing and the second largest stock exchange in the nation.