Long Before the Power Suit

Women’s Suffrage, The Kansas City Call, Della C. Lamb Neighborhood House, Spofford House, Hollywood, Paramount Pictures, Dubinsky Brothers, Sir Carl Busch, Children’s Mercy Hospital, Grand Canyon, Hopi House, Westport House, Union Station, Professional golf, Wyandotte nation

At the turn of the 20th century, the United States was a man’s world. In Kansas City, Mo., it was no different. Most men went off to work in the role of provider, whilst the wives remained home to cook, clean, bear and rear their children. Those same men clocked out, returned home to dinner waiting on the table thanks to those same wives and – to put it simply – had it fairly easy. A woman’s work, it’s always been said, was never done. Ah, the good ol’ days.

Every rule has its exceptions, of course. There were some truly incredible and inspiring women breaking the mold – nay, stamping it beneath their feet – and abandoning the gender roles oh-so-firmly in place at the time. But wait –don’t get me wrong—I’ve done the cooking, cleaning, bearing and rearing myself. I did and do it happily, as a choice, and thankfully, no longer the societal norm.

But long before the power suit that symbolized the shake-up of that norm, these women fearlessly entered the professional world of men… and succeeded.

The Lawyer

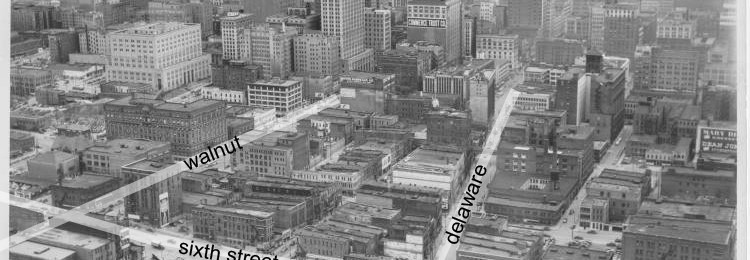

Eliza Burton (1874 – 1946) was better known as Lyda, and the first woman on the Kansas bar. The lady lawyer was of one-half Native American heritage; herself, her two sisters and her mother belonged to the Wyandotte nation. Her mother inherited more than 60 good farming acres, which brought them to Kansas City, Kan., (Wyandotte County) when Lyda was a child. But Kansas City knows of floods… and the flood of 1910 drowned the land and home on those acres, prompting Lyda and her sisters to move to the Missouri side of Kansas City.

She graduated from Kansas City’s School of Law in 1902, joined the Kansas bar then built a fort and shot a gun at a police officer in Oklahoma… Wait, what? You see, Lyda was a passionate person, in life and in work. The United States Department of the Interior offered the Wyandotte Nation a sale of their lands in Oklahoma for cold hard cash. This land was home to a cemetery sacred to both the Wyandotte and to Lyda herself – where several of her family members were interred. Lyda and her sister traveled to the cemetery, erected a crude fort and stood sentinel with shotguns. And yes – she was arrested for shooting (at) a police officer.

Undeterred, Lyda brought forth an injunction that was denied. She appealed, and appeared before the Supreme Court to argue the case. Lyda lost, but she left Washington, D.C. as the first Native-American lawyer to bring a case before the justices of the Supreme Court.

The Golfer

courtesy of Kansas City Golfer

Opal Hill (1891 – 1982) went where only one other woman in the entire world had gone before her: the men’s world of professional golf. It was sheer chance that Opal ever set foot on the golf course. After graduating from nursing school at Trinity Lutheran (then Swedish Lutheran Hospital) in Kansas City, Mo., she married local lawyer Stuart Hill, and hadn’t much thought for the male-dominated sport.

The nurse grew ill, finally diagnosed with an infection of the kidneys deemed incurable by her doctor. Instead of medication, he prescribed a different sort of therapy. Suggesting lots of fresh air and time in the sunshine, Opal decided she might take up golf.

Starting with lessons from a male pro, it was soon clear that Opal was born to be a golfer. She took the crown at the Western Open back to back in both 1935 and 1936, going professional in 1938. She won the Kansas City Women’s Title tournament 14 years in a row. In a row! With a few Western Crown championships under her belt as well, Opal Hill lived a long and lovely life, dying at 89 years of age. Who knew golf was a medical cure?

The Architect

Mary Colter (1869 – 1956), was “…Eccentric,” writes author Ruthie Wornall. “She was a chain-smoking perfectionist who often dressed in slacks and wore a Stetson hat.” Colter was also one of very few women practicing the art of architecture in the United States at the turn of the 20th century. Oft-called the “Grand Canyon Architect,” the Stetson-clad Colter designed, basically, most of the buildings surrounding the gaping natural phenomenon, like the Hopi House and Phantom Ranch.

Her talent and devotion to the rule that “buildings belong to their area” – meaning the use of local materials and historic or native aesthetics – attracted the attention of the architectural magnate Fred Harvey. Obtaining the job with the Fred Harvey Company landed Mary here in Kansas City, Mo. Amongst her notable designs here was the Westport Room within Union Station, a fine-dining restaurant of the magnate Fred Harvey’s chain. Harvey owned a string of restaurants along the Santa Fe Railroad, providing a luxurious atmosphere for hungry travelers.

The Surgeon

Dr. Katherine Richardson (1860 – 1933) relocated to Kansas City in the 1890s with her sister, Alice. Both had earned degrees (in medicine and dentistry, respectively) from the Pennsylvania Women’s College. In those good days, no hospital or practice would consider hiring a female, and the sisters opened their own practice in Kansas City. It just so happens that Katherine and Alice together established Children’s Mercy Hospital – today, one of the top 10 best children’s hospitals in the country.

In 1897, Children’s Mercy first opened under the name of Free Bed Fund Association for Crippled, Deformed, and Ruptured Children. The modest quarters were located within a maternity hospital, the only place lady doctors might practice. It began with just one hospital and one very ill young girl, eventually evolving from the mercy bed to the brand-new Children’s Mercy Hospital on Independence Avenue. Katherine did her best to create a joyful atmosphere for the poor sick children, abound with airiness, light and of course, innumerable toys and activities.

Katherine – though a woman – was among the elite surgeons in Kansas City, and a generous one at that. Because (again, those good old days) African-American people were disallowed from white hospitals, the doctor was forced to turn away black children. To remedy this in her own way, she initiated the installment of a pediatrics program at Wheatley-Provident Hospital in the 18th & Vine, a hospital serving the city’s black community.

When she died in 1936, the good surgeon’s funeral service was held on the grounds of Children’s Mercy hospital.

The Pianist

Sarah (Smith) Busch (1889 – 1939) and her husband were both accomplished musicians, even meeting so serendipitously at a concert in Kansas City. Sarah was here to study music after a brief stint at Howard University in Washington, D.C. Her future spouse, Carl Busch, was an implant from Norway and director of Kansas City’s Philharmonic Choral Society. They married six days following their first meeting at that fateful show.

Courtesy of the UMKC library

Sarah had been playing piano since the age of six; a prodigy indeed. Following her music studies in Kansas City (her parents, realizing her talent, had sent her off from her hometown of Fayette, Mo.), the newlywed Mr. and Mrs. Busch traveled to Europe to study.

Thus Sarah’s fame commenced – after winning a prestigious award overseas, the lady pianist went on to become one of the most internationally renowned players in her profession. But concert after concert, Sarah longed for her husband (by then knighted for his talents), Sir Carl. She gave up the professional pianist life and returned home to her man. How oh-so-romantic! Sarah Busch didn’t give up her music career entirely, after all. She turned rather to music instruction, in which she earned just as much distinction as with her musical talent.

The Actress

Jeanne Eagels (1890 – 1929) was still Amelia Engles when her family moved from Boston to Kansas City, Mo. She was a high-school dropout, but only for necessity’s sake. To help support her family, Jeanne worked as a salesgirl at Kansas City department store Emery, Bird & Thayer. Jeanne did have the fortune of studying under the talented Georgia Brown at The Georgia Brown Dramatic School and Children’s Theatre Arts as a child, which proved its worth when at age 15, the Dubinsky Brothers Traveling Theater hired on Amelia, who adopted the Jeanne Eagels moniker for the stage.

And travel she did, performing with the Dubinsky’s Theater until her move to New York City. Jeanne bleached her hair and became a Zeigfried girl, a regular on Broadway and then in film as well. After working with Paramount Pictures and an Academy Awards nomination, the starlet met an untimely death in 1929, believed to be the result of a fatal drug and alcohol combination. “Jeanne Eagels,” wrote Edward Doherty for Liberty Magazine, “was a genius and a drunkard – an artist and a hellion – a poet and a devil.”

The President

Della Lamb (1897 – 1979) first volunteered as a teenager the day nursery at the Melrose Methodist Church on Fifth Street in the in North Side, watching over children whose mothers worked full-time jobs to support the family. Little did she know, her volunteer work would turn into a lifetime career and the nursery into what is today known as the Della C. Lamb Neighborhood House.

Renamed in her honor in 1946, the home was originally the Institute Neighborhood House for Neglected Children. It was there that Della served as the devoted President of the Board Directors for a quarter of a century. Renowned for her missionary work, Della was also involved in the creation of the Spofford Home in Kansas City, at its opening an orphanage and today a residential treatment and therapy center for children aged 4 – 12. The Spofford Home also offers housing while children wait to be placed in foster care.

Della, too, devoted herself to the Kansas City Council Clubs and the Community Chest, and held the post of President of the Women’s Missionary Society of the Southwestern Missouri Conference. The lady led a life of service and dedication to her causes.

The Publisher

Courtesy of the Black Archives

Ada Franklin (1886 – 1983) was a writer, a teacher and a publisher, and married to the founder and owner of Kansas City’s black-community focused magazine, The Call. Chester A. Franklin and Ada met at Wheatley Provident Hospital, the first hospital in the city erected by and specifically for the care of African-Americans in the 18th & Vine district. In those days, medical care was on the long list of not-so-equal standards. Ada contributed to and helped Chester publish The Call, and upon his death took over the publication entirely. At the time, renowned activist and Kansas Citian Lucile Bluford sat on The Call as editor.

Ada continued with the publication of The Call for nearly 60 years following her husband’s death, earning her multiple awards including the Distinguished Publishers Award and the Curator’s Award in Journalism. Ada also had a talent for screenplay; her show “Milestones of Race” earned praise the United States over.

Mathilde Shelden (1885-1980) was the first Missouri woman to ever hold a political office; Mathilde – better known as Dolly – was a vehement advocate for the women’s right to vote in the United States. A 10-year-old Dolly demanded to know why females didn’t have the right. She dreamed of voting. It was an ever-important facet of her life. After high school, Dolly traveled to Washington, D.C. for a conference. She returned even more politically charged and confident, a Women’s Suffrage advocate rising to the post of Vice President within the Missouri State Republican’s Club, which sent her as delegate to Washington, D.C. in 1919.

Dolly was born and raised in Jefferson City, Mo. It wasn’t until her 30s that she married and moved to Kansas City. Dolly immediately immersed herself in the community, the Kansas City Dental Society Auxiliary (her husband Dr. Frank Shelden practiced orthodontics), the Twentieth Century Club and the City Council.