“Free at last, Free at last…”

Civil Rights, Dr. Martin Luther King, race riots, Harry S. Truman, Twin Citians, Lucile Bluford, M.L.K. assassination, 1960s

Written by Karla Deel with help from Monique Salazar

Civil rights activist. Proponent of equality. Pastor. Humanitarian. Peaceful protestor. Dreamer. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.: the greatest civil activist this nation has known. King won the Nobel Peace Prize for his nonviolent resistance to racial prejudice in America at age 35, then the youngest person to ever receive the honor—and Kansas City had the pleasure of making his acquaintance on several occasions before his untimely death.

Before the infamous race riot of 1968, earlier civil rights protests in Kansas City occurred during World War II, when Kansas City’s black population stood up for its right for employment in war industries. “By 1942,” writes digital history specialist and editor Jason Roe, “these protests, combined with a genuine need for labor and fairer federal policies, won the desegregation of factories supporting the war effort in the metropolitan area.”

In 1947, Missouri’s homegrown President Harry S. Truman, appointed the Committee on Civil Rights, which aimed to enact some civil rights legislature. Many criticized Truman’s decision to take political action toward race issues in America, to which he replied in an address before the NAACP at the Lincoln Memorial:

“As Americans, we believe that every man should be free to live his life as he wishes. He should be limited only by his responsibility to his fellow countrymen. If this freedom is to be more than a dream, each man must be guaranteed equality of opportunity. The only limit to an American’s achievement should be his ability, his industry, and his character …Our immediate task is to remove the last remnants of the barriers, which stand between millions of our citizens and their birthright. There is no justifiable reason for discrimination because of ancestry, or religion, or race, or color.”

April 11, 1957: Nine years before his assassination, King joined local reporters for an interview at the Pickwick Hotel in Kansas City. Built in 1930, the Pickwick Hotel cost 5 million to build, housed up to 300 hotel rooms and a luxurious ballroom that could hold up to 600 people. The hotel, incidentally, closed in 1968, the year of King’s death. After his interview at the Pickwick Hotel, King headed over to an NAACP fundraiser at St. Stephen Baptist Church on Truman Road, where he delivered a speech titled “Progress in the Area of Race Relations.”

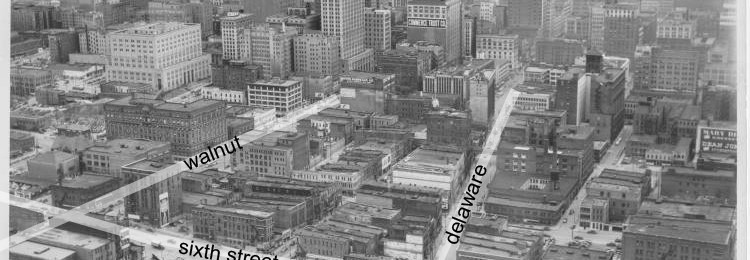

Frustrated by the slow process of desegregation, in 1958, the Twin Citians, a group of black female professionals, alongside Lucile Bluford, editor at the KC Call, protested the discrimination and segregation of the black community in department store eateries. They first campaigned directly to the five largest downtown department stores: Macy’s, Jones Store, Kline’s, Peck’s, and Emery, Bird, Thayer.

After excuses from all businesses, the group formed the Community Committee for Social Action. The group was inspired directly by the speech Dr. Martin Luther King had given a year prior and the success of the Montgomery bus boycott, and led boycotts and pickets of downtown department stores, which resulted in a mass parade through the downtown streets. After several months of protest, they finally won desegregation of lunch counters with the stipulation that black customers undergo “diner tutorials” and a schedule that ensured the restaurant would not be “overrun by negroes.”

Most of Kansas City was desegregated by 1964, and despite racial tension and continued discrimination, the city remained relatively quiet for the next four years…until the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. on April 4, 1968. King was shot on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tenn., where he had been visiting in support of on-strike garbage workers.

April 9, 1968: After the assassination, riots broke out into 100 American cities. It was a clear, crisp day in Kansas City on April 9, 1968, with the temperature hovering around 52 degrees. Maurice Copeland, a 20-year-old African-American man, just home from Vietnam, headed over to Central High School on 32nd and Indiana to gather with the students. While most of the schools across the nation had canceled to honor the life and death of Martin Luther King, Kansas City Missouri Public Schools did not, which offended and incited the African-American community. The students had left school despite the strict admonition by school officials and soon a crowd had sprung up in solidarity. The protestors took over the street and began to march down to 31st and Indiana, turning left at 31st and Woodland. They continued along Woodland to Vine Street and then past Troost Avenue before heading downtown to City Hall – and were joined by Kansas City mayor Ilus Davis.

“Nothing was broken or stolen on the way down there,” Copeland says. “No violence. Something says, maybe a window got broke, but nothing became of it.”

Once they arrived at City Hall, they set up camp and listened to speakers who mourned the death of Dr. Martin Luther King. Curtis McClinton, Kansas City Chiefs player, kept the crowd calm and administered an atmosphere of trust and understanding, meeting with the empathetic mayor Davis on the steps of City Hall. McClinton made the announcement that the rally was going to be moved to the Holy Name Catholic Church on 23rd Street and Benton Boulevard, where he promised that they would spin records, dance and have some hot dogs.

“We were getting ready to go back there, but the police had the place surrounded,” Copeland recalls. “They would not let us leave. Baton to baton, they were standing there…”

A young woman confronted police and demanded to be let out. Ignored by police, she shouted, “If you won’t let us walk home, we are going to walk on your cars!”

Undaunted, that’s exactly what she did, jumping on top of the police car and then swiftly jumping off. The order came to close in on the crowd and pandemonium broke loose. At one point while trying to outrun the police, Copeland noticed a Catholic priest running with them.

“He fell right over in the grass by the Federal Building and the police beat him with batons like he stole something,” Copeland exclaims. “That was kind of shocking, these people were beating a priest.”

This priest was either Father Ed Warner, rector of St. Augustine’s Episcopal Church in Kansas City or Rev. David K. Fly, both who recall first-hand accounts of marching with the students and being clubbed and tear gassed in front of City Hall.

Copeland made it out with a few others and they soon found they were going to have to cross I-70 after jumping a six-foot fence. As they were helping each other over the fence, Copeland heard the pops of bullets coming from the highway.

“I knew whatever they were shooting wasn’t high caliber, maybe 25s or 32s, fortunately they were not good shots.”

Copeland had parked his car on the other side of the highway on 19th street. He piled everyone in his car and drove them up to the church.

“You know, I want my hot dog, I want my coke, they had the DJ from the radio station setting up and there was a crowd there. (…Then the police) closed all the doors on us, and all the windows.”

The basement erupted in tear gas and all hell broke loose as people tried to flee out of barricaded doors. “They tear-gassed us,” Copeland says. “They can’t say they didn’t. After that, it was all over the media that it was a riot.”

Another survivor present that day was Rev. David K. Fly. In a presentation titled, “Reflections of the Kansas City Race Riot of 1968,” Fly shared his understanding of what led to the riot:

“On Monday, newscasters announced that Dr. King’s funeral would be televised the next day. So, the dean of our cathedral and the leadership of the Metropolitan Interchurch Agency, which is a large group of Protestants and Catholics in Kansas City, organized the service at the cathedral for Tuesday morning. Because of the tension in the metropolitan area the Kansas City, Kansas School District cancelled classes for Tuesday, so that students could stay home and watch the funeral. The situation in Kansas City, Missouri was very different. Dr. James Hazlett, the Superintendent of Schools on the Missouri side had conversations with his staff over the weekend; decided he would not cancel school under any circumstances and left town on a business trip on Sunday afternoon. Thus, classes in Missouri were kept open and students were expected to be in school.” Tuesday morning, the dean and I were busily organizing the service as it promised to be a major event attended by most of the clergy in the community, and you can imagine a 26 year old clergyman being in charge of something that massive. What we didn’t know at the time was that while we were putting the last minute touches on the service; large numbers of black students were leaving classes at Lincoln, Manual, and Central High Schools and demanding that they be allowed to go home and watch Dr. King’s funeral on television. When school authorities rejected their request the young people began to demand that they be permitted to march to city hall to protest. Not one single soul was present in the city with the authority to cancel school. Dr. Hazlett was out of touch. The students’ anger and frustration built, some ran through the hallways in the schools kicking over trash cans. The school authorities in some cases called the police and they responded. And, in a couple of situations sprayed Mace on the students. The news that classes weren’t going to be cancelled spread like wildfire as more and more kids left school and ran through the hallways of other schools encouraging students to join them. The kids poured out of the schools and into the streets.”

What happened to incite the exact moment when things turned violent at City Hall is still a mystery, Fly recalls. A youth may have thrown a bottle. A policeman in full riot gear may have excitedly thrown tear gas. Regardless, the streets erupted into chaos. Policemen charged the crowds with tear gas, batons, Mace, and dogs as the youth ran for sanctuary at the Holy Name Catholic Church. On the drive to St. Luke’s hospital, Fly and the cameraman who rescued him drove by the church to find cops barricading the youth into the basement and throwing tear gas in through the “squat little basement windows.”

April 10, 1968: According to a Kansas City Star article printed April 10, 1968, then police-chief C.M. Kelley defended his use of tear and irritant gas in front of City Hall, but didn’t comment on the tear gas used in the basement of Holy Name Catholic church. Likewise, he had no idea what occurred when police knocked down two priests.

The Kansas City riot led to 300 arrests, mostly black youth, seven dead, and a three-block area of Prospect Avenue bombed out and burned down.

On April 10th, one day after the riots in Kansas City, the new junior high school, still under construction at 43rd Street and Indiana Avenue, was officially named Martin Luther King Junior High School by the Kansas City board of education.

Despite the violence that occurred on the streets of Kansas City on April 9, 1968, the demonstrations brought white and black together, standing on the steps of City Hall, in honor of the man who fought tirelessly for equality and civil rights. And still today, we gather together and march forward, fighting, always, for freedom for all.

“Free at last, Free at last, Thank God almighty we are free at last.”