Field Guide for Redlining a City

Redlining, Black History, Real Estate, J.C. Nichols, Racism, Troost Avenue, Segregation, KCMO, Hyde Park, White Flight, New Deal, Troost Avenue, National Housing Act of 1934

Why don’t black and white Americans live together? asks a story published by the BBC in early 2016. The piece delves into how, despite “legal” segregation having ended over half a century ago, many American cities are still facing incredible amounts of neighborhood-to-neighborhood racial divides. In its exploration of this phenomenon, it is noted that Kansas City, Mo., in particular is, “one of the country’s most segregated cities.” Currently Kansas City is ranked as the 36th most segregated city in the country. And while this number is better than it was just a few years ago (Kansas City was ranked 18th in 2000), the shift can largely and ironically be attributed to suburban integration. Even in recent years, neighborhoods in the city’s urban core have seen little improvement in their diversity.

Throughout the 20th century, the United States government drew heavy handed racial lines. We still can see the remnants today. Even a few generations removed from Jim Crow America, the geographic lines that kept blacks and whites divided into separate neighborhoods still persist. In Kansas City, this translated to keeping blacks east of Troost Avenue and south of the Plaza/Brookside districts. New Deal policies notoriously allowed for strict guidelines as to where subsidized home loans could be issued and to whom they could be issued. “Redlining” as it came to be known, was the practice of denying housing services (either directly or by fixing prices) to people of color in order to control the racial makeup of a particular area. This was a notorious practice and widely done in the years during and following the Great Depression, beginning with the National Housing Act of 1934.

While housing segregation certainly existed before 1934, making it allowable through federal policy did much to exacerbate the decay of many cities’ urban cores. Black neighborhoods were often officially seen as too precarious to invest in and, as a result, many blacks were denied equal access to this new wave of home ownership. At the time it was perfectly permissible for underwriters to deny funds on the basis of race. As a result, from the Depression up through the Baby Boom, countless black families were denied what was, at the time, the single most important factor when it came to entry into the middle class. Predating even the many racist tendencies of New Deal policies, the city’s most celebrated turn-of-the-century land developer, J.C. Nichols, became well-known for his efforts to legally thwart minority entry into any of his neighborhood developments, most notably barring blacks and Jews from moving into homes in his Country Club District. These practices remained legally binding until the mid-1940s, but had lasting effects for generations.

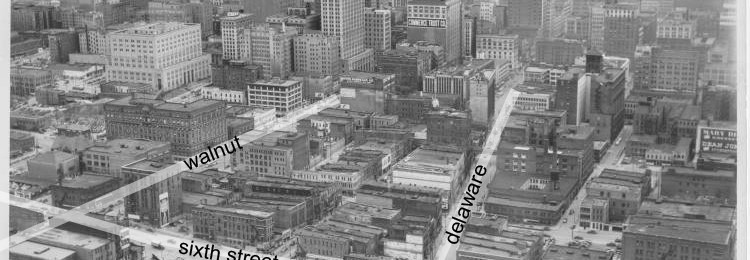

This type of behavior was a common practice in urban areas all throughout the country. So why in particular does Kansas City still battle today with such staunch geographic segregation? As with many other cities, 1960s Kansas City was fraught with rampant urban decay. Inner city neighborhoods were all but completely forgotten and many formerly bustling streets and districts were socially dismantled. At about this same time, Kansas City also began to annex unincorporated areas of its metropolitan area left-and-right. By the early 1960s, in fact, it got to a point where, geographically, Kansas City became among the largest cities in the country—all while the city’s interior was suffering from a sizable population decrease.

One of the more unanticipated consequences of this massive geographic expansion was the re-segregation of the city proper. While many strides where made during the Civil Rights Era to integrate Kansas City’s neighborhoods, much of this progress would be undone. During these years of rapid annexation and suburban expansion, old buildings—mostly residential and largely historic—were destroyed to make way for office space and parking lots. The urban core became a place to travel to for business (if ever) and white flight continued at an unparalleled rate through the 1960s and beyond. Residents who could afford to do so moved to one of the city’s seemingly ever-expanding and rurally suburban destinations, which reached far outside of anything one might think of as being part of a metropolitan area. Most cities around the country experienced the ill effects of suburban migration. However, it seems that Kansas City’s extraordinary sprawling expanse during the mid-20th century, at least in part, made the housing troubles of the inner core all that more easy to forget and leave behind.

Today, the divisive housing practices of the past can still easily be seen with a drive down any border of one of yesteryear’s “redlined” neighborhoods. In the Hyde Park neighborhood, for example, the social divides are still very real. Hyde Park runs north-south from Linwood to 47th street and east-west from Gillham to Troost. Through the early 20th century, Hyde Park was a district filled with the large homes of affluent businessmen who worked downtown. Many of these homes still stand, are in good shape and are worth a good amount of money. The lawns are mowed and the crime rates are low. However, one only has to travel a single block away for the reality of the city’s divisive past to become clear. Across the street from the neighborhood’s eastern border runs Troost Avenue, the longest redline border the city had in all of the 20th century. Directly across the street from the lushness of the Hyde Park neighborhood stands blocks with no lawns, dilapidated shops and homes with boarded up or smashed in windows, and cheap strip malls often containing nothing but tobacco and payday loan stores. This is a black neighborhood. And in 2016—directly across the street from what affluence looked like a full century ago—the racial divides are anything but a thing of the past.