Drawing the Line

Troost Avenue, The Troost Wall, Porter Plantation, Millionaire’s Row, L.V. Harkness, The Landing, segregation, J.C. Nichols, redlining, Redeem the Dream

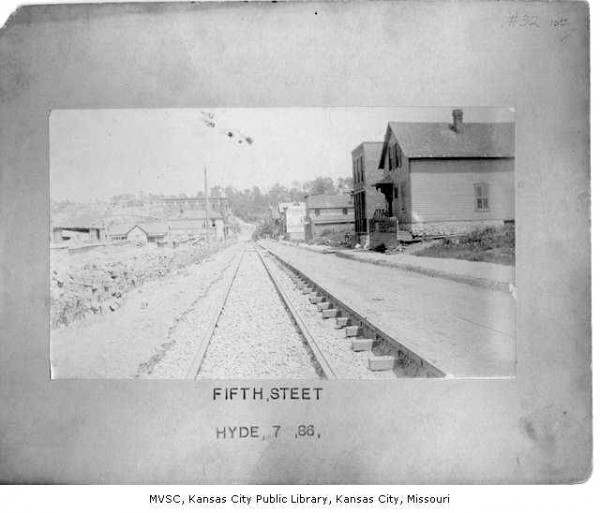

Missouri Valley Special Collections, Kansas City Public Library, Kansas City, Missouri

Something there is that doesn’t love a wall…

–Robert Frost

My mother’s father was the first of the big, Italian Santoro family to be born on American soil. His would be the last generation to put their hopeful eggs in the basket of the almighty American Dream. He found a wife—she was the first American of her big, Italian clan, too—started a family, and rose early with the sunrise to sell fresh produce from a cart. In the 1950s they moved from their humble home in the Italian ghetto of downtown Kansas City to a sizable brick house in the up-and-coming Brookside area, just two blocks away from one of the reigning roads in Kansas City, Troost Avenue.

He bought a wood-paneled Oldsmobile station wagon. Every Sunday, his wife, Mildred, prepared a spaghetti feast for their growing family. They had nestled in to the most idyllic of suburban communities, enjoying the company of fellow Catholic baby boomers migrating just south of the midtown bustle to enjoy big houses and modern conveniences. The neighborhood was premier, and for an Italian-American like Sam Santoro it was the American Dream. Mom-and-Pop stores cropped up along the avenue, and Troost rang in the 1960s booming. The crowded bus lines, the eager storefronts, the sense that folks had really arrived, all glowed sweetly over Troost like the dim burn of the summer streetlights.

That warmth and wealth has all but abandoned Troost, and the name has become synonymous with crime in the black community. At least, that is how the exorbitantly white and affluent neighborhoods to the west see it. Now, the Brookside of lazy summers and happy Catholics exist just before Troost—the wall that separates that community from the predominantly black neighborhoods to the east. It is a dividing line as staunch and stubborn as a towering wall made of stone, only much easier to see the other side.

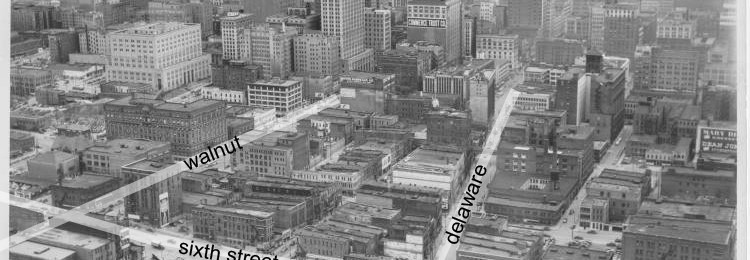

Troost Avenue runs north to south through the Kansas City metropolitan area; its four lanes stretch over 50 city blocks; its name is a valued signifier to locate an array of distinct neighborhoods. These are the defining truths about Troost that have not changed. But while its recognizable name once stood tall with the illustrious likeness of Main Street and Broadway Boulevard as a major throughway for the urban area, Troost today has a far less stately reputation.

That distinction of esteem migrated strictly to the west. The Brookside neighborhood that stretches just a block away from Troost Avenue out to Ward Parkway is one of the densest concentrations of wealth in the state of Missouri. To the east side, real estate prices are less expensive than 83 percent of all other Missouri neighborhoods. The rate of vacancies is comparable to US neighborhoods made up of primarily seasonal vacation homes. Widespread poverty and higher crime rates have become the cultural fixtures of neighborhoods on the East Side from 5th Street to 75th Street.

Invariably closed and endangered businesses dot Troost Avenue. The ubiquity of predatory payday loan centers and pawnshops, and their proximity to storefront childcare missions and youth shelters, create a tapestry of economic hardship. Fish shacks and old churches are beacons of life and community still thriving on the street; but heavy hangs the sense of a unity forged by struggle instead of a community reaping success.

Where the avenue stretches today was first a canoe trail for the Osage Nation. The lands were sold to the United States in 1808. A large portion would become the esteemed Porter Plantation in the mid-19th century. At one point, over 100 of Kansas City’s black population would live and work on this plantation as slaves.

After the Civil War, the Porter family dissolved the plantation and began selling the real estate. The grounds would be incorporated to become “Millionaires’ Row,” home to some of the most successful white men who had so valiantly made the land their own.

In 1888, L.V. Harkness–the richest man in Kansas City—moved to Troost Avenue.

Photo courtesy of Missouri Valley Special Collections, Kansas City Public Library, Kansas City, Missouri

In 1951, Sam Santoro planted his young family in the newly developed south section of Troost. It was no “Millionaires’ Row,” but it was the Taj Mahal to an Italian fruit salesman. My mother, the baby of the brood, remembers carefree summers on Troost. Her older brothers kept begrudged care of the aggressively green lawn, and the Missouri heat hung lazily around the shoulders. It was a family neighborhood, so she was never for lack of a companion. Her best friend Rita lived just two streets over, and the long afternoons allowed walks to the community pool or just air-conditioned refuge with teen magazines and the record player.

It was the late 1960s, a time when the world was opening up for young girls with a summer day and time to kill. Brookside was developing as quickly and unexpectedly as their jumper-clad bodies. Kansas City’s first indoor mall had opened on Troost, just four blocks from my mother’s house. It was called The Landing, and it was an oasis of lush indoor plants and a sparkling new Macy’s only yards away from the girls’ stomping grounds. Its open-air courtyard boasted a whimsical Noah’s Ark fountain, and families from all over the metro area flooded in to enjoy the novelties of air-conditioned shopping sprees. My mother had found a new playground; her mother bought new clothes at the Macy’s. It was as if downtown had come to their little town. The cars zoomed in and out under the Landing’s entrance, a bright blue archway with the mall’s name scrawled in a childlike scribble. The cars zoomed down Troost Avenue, and the riders looked out to see the optimism of a golden summer in a proud American neighborhood.

The Landing stands now, barely, as a pouty reminder of the bygone days of carefree commercialism on Troost. Its weathered white paint coat and dated architectural design have spent decades begging to be noticed, to be tended to, but remain painfully stuck in the past. The grander wings that were once department stores were long ago removed and paved into parking lots. The Payless Shoe store is the only veteran business that has survived longer than five years in the droopy half-mall. The neon sign buzzes tiredly, a moody amber glow of dogged indignation. Most passing drivers who live west heave a grieving sigh at the perpetually empty parking lot. Many do not realize it is still a mall.

Though the Landing may not exude its same 1960s curb appeal for the white families of Brookside, it still serves as a beloved shopping spot for the black community to the east. KC Gold Fronts proudly propagated the grills fad of the early 2000s. One younger addition is a GEN X clothing chain, a midsize urban outfit that designs for black teens. It is one of many clothing stores on the block: a wide variety ranges from a handful of second-hand thrift sores to a debonair suit shop adored by the men in the community, Harold Pener’s. Meanwhile, the boutique shops in Brookside offer next to nothing to serve specifically black markets.

The racial makeup of the neighborhoods is no accident. The history of segregation on Troost is almost as old as the street. After the real estate boom that created Millionaire’s Row busted in the 1890s, black buyers were able to purchase luxurious homes as eager sellers went temporarily colorblind. Blocks that just decades before had been plantation land were suddenly occupied by black homeowners. For the burgeoning black middle-class, Troost was the place to be. For real estate developer J.C. Nichols, mastermind of the Plaza shopping center, Troost was the line to avoid when creating his wealthy subdivisions.

In the early 1900s, Nichols developed communities like Crestwood and Brookside just west of Troost, fostering neighborhood associations that explicitly excluded black homeowners from membership. White and black middle class families rushed to fill nearby neighborhoods to the east, carving out their own slice of luxury in the booming midtown area. Several associations followed Nichols’ model on the East Side, creating pockets of racial segregation within the quarter. By the time the 1968 Civil Rights Act outlawed practices like Nichols’ redlining, white families fearing declining property values began leaving their East Side homes in droves.

In 1968, my mother was in middle school at St. Peter’s, a Catholic elementary just three blocks blocks west of her house. While global paradigms were shifting at a dizzying rate, she was weathering her own adolescence. The closest thing to a sexual revolution in Brookside was a trench coat flasher who exposed himself to my mother and her sister on a walk home from school one traumatizing day. The neighborhood was changing, but things seemed to stay the same at the Santoro household. Sam brought home the less-desirable produce for his wife Mildred to prepare a five-course meal of Italian decadence, every night. Grandma Rafaela, an old-world relic who spoke not a word of English, lived in the basement. Sam Santoro had his own business and supported four children and one elder under the roof of his own home. They had every reason to feel secure and satisfied with their piece of the pie.

On April 9 of that year, an announcement buzzed in over the St. Peter’s loud speaker that Martin Luther King, Jr. had been shot and killed in Atlanta. Parents were notified and classes were hastily dismissed that afternoon, for fear of impending riots in the neighborhood. My mother waited anxiously for her older brothers; what was only a five-minute walk home suddenly seemed like a death march. She had seen race riots on television but had not considered their likelihood in her quiet neighborhood. Neither had many white families living on the East Side, who after the panic during an ensuing five days of rioting that April began to see their communities as erratic, dangerous, and undesirable.

The Santoros stayed, and by the end of the 1970s they were one of the only white families on their block. By the time my mother entered high school three years later, the majority of her friends had moved south to the suburbs. She would dodge questions about where she lived to her more privileged classmates at St. Teresa’s Academy. In two short decades, the house off of Troost had gone from a symbol of pride to a socioeconomic scarlet letter.

The home my mother would eventually purchase was also off 63rd Street, but closer to Ward Parkway than Troost Avenue. I grew up there, enjoying a most idyllic childhood of front lawns and front porches, neighbor kids and walking to get ice cream. I went to the same St. Peter’s school building until 8th grade. My grandmother lived in the same Santoro home she had since the 1950s. When we visited, it felt like traveling to a different planet. It was only three blocks away from school. I never went to the Landing; I didn’t walk down Troost on summer days. The avenue was an unspoken but firmly felt dividing line. The barrier was difficult to understand as a child—what stopped and started on Troost and why?

This August I participated in the Redeem the Dream march on the fiftieth anniversary of Martin Luther King’s March on Washington. The march barreled through the East Side on Benton Boulevard, a crowd of hundreds—all ages, races, and creeds—honoring one of the most significant appeals to racial integration in history. Concluding at the Brush Creek Amphitheatre east of the Plaza, marchers were treated to a performance of the “I Have a Dream” speech and keynote addresses from local leaders in the black community. The same issues still prevailed, with words on segregated neighborhoods and stifling poverty on the East Side. The peaceful demonstration was a far cry from the week of mayhem that ensued after Dr. King’s death; the sense of adversity felt more focused, but no less urgent.

As Kansas City continues to grow and redevelop, there is still Troost Avenue—a storied street of success and failure that continues to draw a line in our community. Unlike a wall, it will not take brute force to tear down. Instead, the Troost barrier will be demolished only when its optimism is restored. Community activists are working to restore a promise in the surrounding neighborhoods, that a family of six can pursue its American Dream and find success, security, and a home that will stand as its own kind of mansion.