Born of this River

Francois Choteau, River Market, City Market, Civil War, Pacific House Hotel, Hannibal Bridge, Gillis Opera House, River Quay, mob wars, Kansas City mafia

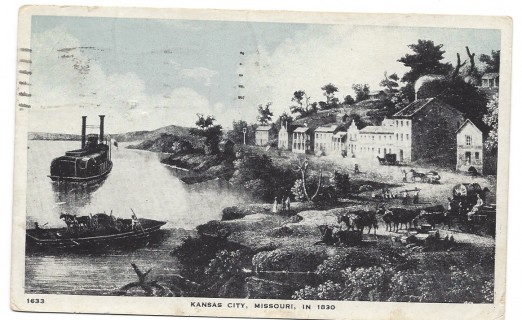

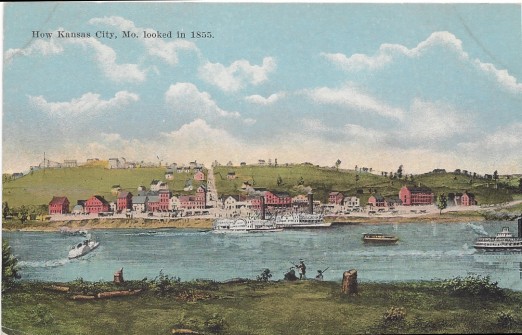

French fur trapper Francois Choteau and his wife, Berenice, settled post on the Missouri River in 1826, and helped to establish the area we know as the River Market—nowadays an urban neighborhood just south of the Missouri River in downtown Kansas City, Mo. Originally, Choteau relocated his wife and children west from St. Louis to settle along the Missouri River not far from the mouth of the river known in 1821 as “River Canses.” He relied on a close proximity to Indian territories, trapper clients and river transportation in order to sustain trade. The ebbing and flowing of the Missouri River as it joined with the Kansas River provided a natural levee that helped transfer goods from river to wagon, stoking the economic trade in the area. In the 1800s, lush forests of hickory, oak and walnut towered over the unkempt river plane and upland meadows. Only sparse nomadic trappers and fishers could be found roaming the riverbed and fertile forests

Since its inception, the River Market (platted in 1839 as the Town of Kansas) has always been a place of diversity—a place for all people. In the mid-1800s, Indian trappers, astute businessmen and inventors, pioneer familes and everyone in between flocked to the promise land of a rough-cut river town. “Anything goes” seemed the mentality that helped shape the district and eventually, Kansas City.

“In the 1800s,” writes Paul Kirkman in his book Forgotten Tales of Kansas City, “the ‘easy’ way West ended at Missouri’s western border…” Beyond Missouri’s western edge, low plains stretched thick with prairie grass. Threats of “wild” natives and lands so prone to violent storms, tornadoes, hail and blizzards kept travelers leery of going beyond the small town on the river. With no reliable westward river transportation, travelers who made it as far as the Western border of Missouri then chose to go by wagon or on foot to push westward. Missouri became, in essence, the last safe place before the great unknown.

By April of 1846, 100 lots had been sold to the public and all 150 acres of land we now know as the River Market neighborhood saw rapid growth. By 1847, the population of the “Town of Kansas” had grown to 700. The neighborhood’s City Market, still the Midwest’s largest open-air market, which occupies almost 10 acres of land, has existed since 1857. According to the National Register of Historic Places, the City Market in Kansas City continues to be one of the “largest wholesale fruit and vegetable markets in the United States.” On most Saturdays and Sundays throughout the year, local farmers and crafty folks occupy stalls in the City Market and sell their harvests and wares to market goers.

Thanks to Kansas City’s Gillis family, a leading pioneer family who donated the land currently used for the market in 1846 “for public use forever,” the City Market remains a year-round eclectic and free destination for people of all ages. You’ll find funnel cakes, snow cones, train rides made from hollowed-out plastic barrels full of children pulled behind John Deere tractors, inflatable slides and bounce houses, musicians playing homemade instruments or street performers poppin’ and lockin’. More than 675,000 people visit the City Market every year to find nearly 150 farmers, artists, crafters, entertainers and food vendors performing and selling everything from local, organic micro greens to handmade dream catchers and finger puppets crafted from felted wool.[1]

The Civil War stopped most growth in the River Market and Union soldiers ran the neighborhood. The Pacific House Hotel at 401 Delaware St. was considered the finest in Kansas City at the time. Frank and Jesse James were said to have played billiards and lounged at the bar. During the war, the Union Troops occupied the hotel from 1861 to 1865. On August 25, 1863, while standing in the foyer of the hotel, General Thomas Ewing issued his infamous Order No. 11 that forced evacuation of property on anyone who could not prove their loyalty to the Union. This order was considered one of the harshest and cruelest measures of the American government against its people. Properties in Jackson, Cass, Bates and Vernon counties in Missouri were burned to the ground, animals stolen, and many families left with nothing. The goal was to stop Pro-confederate “guerillas” from finding provisions or shelter in the countryside. All hay and grain was removed from fields or burned. Some innocent civilians were stranded without shelter or food and others were still not safe even after evacuating with their wagons and leaving their homes. Wagon after wagon was looted and many families killed. This scorched-earth military policy ultimately had an inverse outcome from what was intended.

In 1869, just after the end of the American Civil War, the Kansas City Bridge, also known as the Hannibal Bridge, designed by Octave Chanute—who also designed Kansas City’s stockyards—became the first bridge to span the Missouri River, which connected Kansas City to Hannibal and St. Joseph railroads. This rendered river trade virtually useless. But progress is progress, right? This swing bridge could open in under two minutes, and gawkers came from far and wide to witness such a feat. After a hellish 1886 tornado that severely damaged the $1 million bridge, it had to be reconstructed 200 feet upstream, where it still stands today.

Progress is progress, but the rails and the bridge made for some negative changes to the community of the River Market. Trains were reliable and the river was vulnerable to inclement weather. Railroads became the year-round reliable source for commercial activity coming in and out of Kansas City. This new development transitioned the people of Kansas City away from the river. Main Street leading south replaced the “natural” levee that existed at the confluence of Kansas and Missouri Rivers. For years, this levee had provided a landing place for river trade, but everything changed in the years that followed the implementation of the railroads. The River Market became a transient town of prostitution, cheap hourly hotels and hostelries and saloons. It was considered lawless by even the outlaws of the time, but even that didn’t stop people from buying local produce.

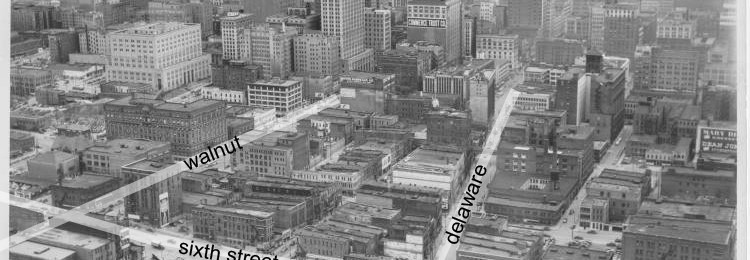

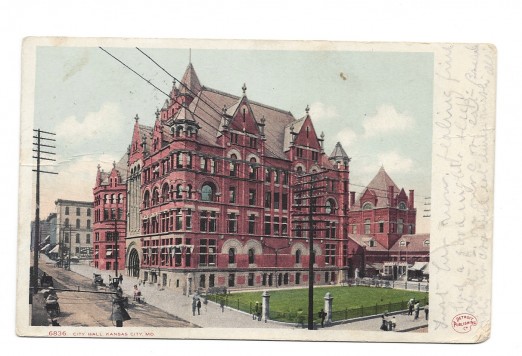

In 1888, roughly 30 years after the Schiebel brothers first erected the modest market building near the river, the city constructed a new brick market building with 56 vending stalls at Walnut and 5th Streets. Despite the Town of Kansas consisting originally of little more than a few rows of crowded buildings along muddy and unpaved roads with boards for sidewalks slung between raw bluffs and deep ravines covered thick with brush, the help of places such as the Gillis Opera House (5th and Walnut) that brought in more than 1,700 people on its opening night on Sept. 10, 1883, encouraged the surrounding communities to remain interested in this wild neighborhood just south of the river. The Gillis Opera House, (designed by Asa Beebe Cross) drew in the finest performers and quickly became the most beloved place in the region to see opera. Despite its opulent size and polished glass chandeliers and fine Walnut that coated its interior, it only cost $140,000 to build. Unfortunately, once the river trade slowed and the city started to develop south, the Gillis Opera House went from hosting large budget opera to showing bloodthirsty melodramas and late-night burlesque shows. When it comes to being resilient, anything goes, right?

In 1910, in order to keep up with refrigerated rail cars that carried food in from as far as South America, the city purchased the land between 3rd and 4th Streets, which doubled the size of the City Market. During the pioneer days, the City Market was a catch-all for commerce, horse trading, medicine shows, political rallies, and circuses; and when merchants aimed to increase the number of shoppers at their stalls in the City Market, they would hire trapeze artists to perform under suspended balloons in the sky.

Though 130 years later you can no longer listen to Mademoiselle Hortense Rhéa belt her famous French-tinged lines as Beatrice from Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing, you can still saddle your Toyota Prius to the curb of 5th and Walnut and go grab some Wi-Fi and a hand-crafted latte, loose-leaf tea or a dish of food adhering to the nations latest “paleo diet” obsession in the buildings most recent incarnation: Opera House Coffee & Food Emporium.

The 1920s-30s found the neighborhood and its residents in shambles. Luckily, according to an on-site plaque in the City Market, the deterioration of the City Market buildings and community during this time was met with a $500,000 investment in 1931 provided by the Ten Year Plan and New Deal. It aimed to strengthen the community and stimulate its economy. Because of this sweep of funding and the start of what was hoped to be a change from the Depression-era, everything was bulldozed in the City Market area, including the city hall, police station and fire station. Since a lot of people were driving into the City Market, land was relegated for the building of parking lots—the whole neighborhood was being made anew. It is said that when buildings fell, crowds would gather around to watch dogs chase the rats—a hint of what effect the depression had on the once-prosperous community. In the ‘40s, the City Market served many social purposes, such as regular jazz dances at night—lit by a system of street lights, referred to then as “the white way”—and a public space for rallies against the war. The River Market found several years of success followed by years of torment followed by years of success then years of torment.

In the 1970s, real-estate developer, Marion Trozollo, saw redevelopment potential in the remaining underutilized and old 19th-century buildings of the River Market. His vision turned into the River Quay (pronounced “key”), a revitalization that repurposed abandoned buildings into galleries, café’s, nightclubs, boutiques and lofts. Trouble began when William “Willie Rat” Cammisano moved his strip clubs from 12th Street to the River Quay, bringing with him the baggage of a shady red-light district with blood on its hands. William’s brother, Joe, owned several bars in the River Quay. He competed against Fred Bonadonna for patrons. Bonadonna owned Poor Freddie’s and several other properties in the neighborhood and publically opposed pornography and the arrival of Cammisano’s strip clubs and X-rated theaters in the family friendly neighborhood of the River Quay. This opposition, plus Bonadonna’s hold on the parking lot racketeering, set up great tension between the two men and their affiliates. “Freddie Bonadonna,” writes the editor of mobbedup.com, “had an exclusive contract to lease night-time parking rights in City Market parking lots. Outfit members became jealous of Freddie’s success. This, in addition to Freddie’s resisting the introduction of mob controlled strip clubs into the Quay, set into motion a series of violent and deadly events.”

The Cammisano brothers and their affiliates approached David Bonadonna, Freddie’s father, in an attempt to get him to convince his son to lay off the developing vice trade in the River Quay. After Freddie refused, David was found stuffed in the trunk of a car at 9th and Olive Streets with five bullets in his skull. Freddie struck back by catching fire to a Cammisano-owned tavern in the River Quay. The war went on with slayings and bombings until all that was left of the River Market district was the broken skeleton of our original town site. “The River Quay was dead by late 1977,” writes Frank R. Hayde in The Mafia and the Machine, “an eerie urban landscape of boarded-up and bombed-out buildings studded with creepy peep shows—a phantasmagoric monument to mob war.”

In its golden days, the River Market was a prosperous river community full of risk takers, visionaries and economic potential. It’s not so different today. The River Market remains a creative melting pot—from young tattooed parents and older couples committed to never cutting another stab of grass, to Kansas City’s next generation of venerable lawyers, bartenders and ex-cons—all stitched together under a blanket of ingenuity and the neighborhood’s ability to adapt. You name it. Anything goes. By day, the restaurants brim with suits and heels from downtown skyscrapers, but by night, the streets are empty except for the resident boozehounds, dog-walkers, joggers and bridge dwellers. Anything or anyone goes here. The wealthy and the homeless living on the same block; the ones who spend a million on a one bedroom and the ones who need low wage-based rent. An Ethiopian restaurant shoulder-to-shoulder with a barbecue joint. Smells of Prince Edward Island from a four-star French restaurant blending with the Vietnamese herbs wafting from the barred windows of the Hung Vuong Market next door. Hydroponic gardening. A boutique cupcake bakery. A 3 a.m. bar committed only to the game of hockey (and battered food). It’s a neighborhood with many faces—old and young, happy and humble. It’s the place where you can smell the Kansas City smell—earthen fumes of the dirty Missouri River, a blend of curry and saffron forever finishing with a note of roasting coffee[2]. The River Market was Kansas City before it knew it would be Kansas City—we are born of this neighborhood, which makes us tough folks. It’s the neighborhood that has skittered a time or two under Kansas City’s dirty rug when commerce shifted residents further south in the late 19th century and after the fail of the River Quay project in mid-1970s. But even facing a wasteland of abandoned industry, and walls of turned backs, from both government and people, resilience has always been the key to this neighborhood’s success.