A Tour of Elmwood Cemetery from the Comfort of Your Recliner

August Meyer, Kansas City Parks Board, George Kessler, City Beautiful, Kersey Coates, Kirkland Armour, Armour Chapel, Mary Atkins, Annie Chambers, Ella the Deer

When you drive up to the 43-acre Elmwood Cemetery you encounter gravestones dating back more than 140 years and family crypts covered in furry moss. A few groups of friends and families with paper guides in hand discover the secrets of the self-guided walking tour. Passing over a stone bridge leads you into the fields of hand-carved headstones, some towering more than 10-feet tall. Elmwood Cemetery is home to more than 36,000 of Kansas City’s founders, mayors, architects, teachers and doctors.

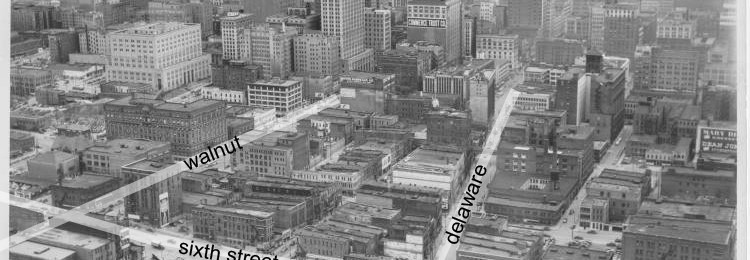

The cemetery, opened in 1872, was spearheaded by August Meyer, the first president of Kansas City’s Park Board (who is also buried in the cemetery), and designed by George Kessler, Kansas City’s famed landscape designer who developed our city’s intricate road system. The cemetery is now listed on the National Register of Historical Places. Its park-like aesthetic was no mistake. Cemeteries of this day were built not only for the deceased, but also for the living to enjoy outdoor events such as picnics.

The cemetery’s first resident was little Sallie Ayers, a 6-month-old baby girl who died from “summer complaints,” which most likely would have been diarrhea caused by bad milk. Soon enough, many Kansas Citians who helped our town grow into the prosperous city it is today decided to make this well-manicured, quiet cemetery their final resting place.

Here are a few:

Kersey Coates (Sept. 25, 1823-April 24, 1887): In the 1850s, the Civil War was a-brewin’ and tensions grew in the Midwest. In 1854, Kersey Coates, a lawyer from Pennsylvania, made his way to Kansas City to pursue a career in real estate during the early fight for land in the unchartered Midwest. When he arrived, he found himself among the company of pro-slavery southerners, including Missourians, who were trying to turn Kansas into a slave state. He soon made a stance to fight for freedom in Kansas and keep it a “Free State.” Although Coates was known as a gentle man, he was not afraid to show his strength. He used his law background to allow the “Free State” party to officially form Kansas into a slavery free state. He soon moved to Kansas City where he became a partner in the area’s first bank and director of the newly formed railroad system. He also invested in the Hannibal Bridge, which is thought to have helped turn Kansas City into the “gateway to the west.” Coates also invested in the area’s west bluffs that overlooked the Missouri River, now known as the Quality Hill area. He later opened Coates House Hotel and the Coates Opera House just a few blocks east of Quality Hill. He died at the age of 63.

Kirkland Armour (April 10, 1854-Sept. 27, 1901): Kirkland Armour was the “meat man” of Kansas City. Hailing from Chicago, Armour, along with his brother and uncle, Charles and Simeon Amour, moved to Kansas City from Chicago in 1870 to build-up the cattle industry in the West Bottoms. Before he knew it, the Armour Meat-Packing company boomed into a profitable business. Before the Armours came to Kansas City, locals only purchased dried or canned beef. Thanks to the brothers, Kansas Citians were able to enjoy fresh beef during the fall and winter. Then, once refrigerated trains were invented, everyone was able to enjoy meat year-round. However, Armour didn’t only provide Kansas City with protein, he also was quite the advocate for the overall well-being of the city. When he wasn’t breeding high-class Herefords, he put his time into investing in the city’s roads, buildings and even cemeteries. Armour Road was named after Kirkland’s uncle, Simeon, who was on the city’s first park board. Armour then bought the Elmwood Cemetery in 1896. He, along with a few others, transformed the cemetery into a not-for-profit organization and negotiated with the state of Missouri to establish a 999-year charter for “perpetual protection.” Even though Armour was thought to be a dashing and fit fellow (according to the Kansas City Journal Post at the time of Armour’s death in 1901) he became fatally ill with Bright’s Disease, which is now known as kidney disease. He died at the age of 41 and was rightly buried in Elmwood Cemetery.

Amour Chapel: In 1904, soon after the death of Kirkland Armour, a wealthy meat-man of Kansas City, his wife, Annie Armour, spent $35,000 to build the castle-like Amour Chapel in the center of Elmwood Cemetery. Annie Armour employed B.H. Marshall of Chicago, and local Kansas Citian George Mathews to design the chapel. It was built by a local stone-mason named Archibald Turner, who is also buried in Elmwood Cemetery. The chapel was built to provide patrons (the chapel seats 80) with a beautiful place to perform funerals. The first funeral at the chapel was that of 32-year-old Mrs. Della Marple on March 16, 1904. In 1922, Charles Armour installed the well-known stained-glass windows. The chapel serves as a timeless reminder of the loved-ones of Kansas City who have passed.

Mary Atkins (1836-1911): Mary McAfee Atkins was a reclusive, timid schoolteacher who hailed from Kentucky. She married her childhood friend, John Burris Atkins, and followed him to Kansas City in 1878. Her husband became quite wealthy while working in real estate during the land-rush in the area. When her husband died, she was left with a sizable estate of about $250,000, which would be almost $6 million today. Because she bore no children of her own, Atkins asked her niece to live with her. Her niece later married a man from Europe and left Atkins. Atkins decided, hesitantly, to visit her niece in Switzerland and soon became a world traveler. During her travels throughout Europe, she developed a love for art from visiting lavish museums in Paris, Rome and London. Thanks to Atkins’ frugal lifestyle and careful money management, her estate rose to be almost $1 million. Upon her death in 1911, much to her family’s surprise, Atkins donated a generous portion of her estate, which at the time was about $300,000, but grew over the years to just shy $1 million, to fund an art museum: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Now, in part because of her generosity, Kansas City has a world-renowned art museum that has put us on the map.

Annie Chambers (June 6, 1843-March 24, 1935) born Leannah Loveall in 1846, grew up to become Kansas City’s most notorious Madame. She started out with a happy life. At a young age, she married an older gentleman with the name of Mr. William Chambers and soon had their first son, who didn’t make it past his first year. Tragedy struck poor Leanne once again while pregnant with her second child. Leanne and her husband were involved in a terrible horse-and-buggy accident leaving Leanne in a coma and her husband dead at the scene. When she awoke, she learned about her husband’s death and shortly thereafter her second pregnancy ended in a stillbirth. Heartbroken, worn down and distraught, Chambers changed her name to Annie and moved to Indiana to lead a life working in the “oldest profession in the world:” prostitution. After a few run-ins with the law, Chambers made her way to wild, cowtown Kansas City right as the Hannibal Bridge opened in 1869. Thanks to the constant flow of prosperous cattle and real-estate business men provided by the newly constructed railroad system, Chambers opened her very own brothel in 1872 near the southwest corner of 3rd and Wyandotte Streets in order to cater to their “needs.”

Her resort soon became the cornerstone of Kansas City’s “red light district.” Annie’s Resort, a two-story, 25-bedroom bordello was a top-of-the-line brothel with glass chandeliers, elegant furniture, and the women were well-known around the nation for being beautiful and even well-mannered. Chambers ran a successful business for years despite the fact that the Kansas City Police headquarters was merely blocks away from the brothel. Now why wouldn’t the policemen shut her down? *hint hint* However, eventually the public outcry to end the brothel forced Chambers to close her prostitution business in 1923. At the ripe old age of 91, Chambers “found” God and peacefully died in her home on March 24, 1935. She rests her large frame in Elmwood Cemetery.

Ella the Deer (May, 2010-Sept., 2013): Elmwood’s furriest friend was Ella the deer. Born in 2011, Ella lost her mother to a car accident. Instead of fleeing the area, Ella made her home at the cemetery. She was known to be incredibly friendly toward visitors and would often follow them to graves. Ella became a national star in 2012 when she befriended a stray dog. Ella and her other four-legged friend spent their days together until winter set in and the dog was put in a shelter in order to keep it healthy and safe. The dog has since been adopted. Unfortunately, tragedy struck when Ella was shot down in September of 2013 by a 19-year-old man who claimed to be hunting for food for his family and said he didn’t know the deer’s story. Ella was cremated and her remains now rest near the Armour Chapel, in the heart of the cemetery, and also in the hearts of all who knew her.