Toad-a-Loop: A West Bottoms Mystery

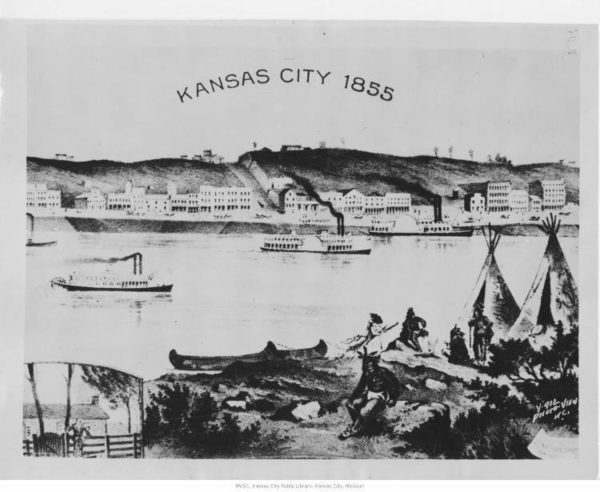

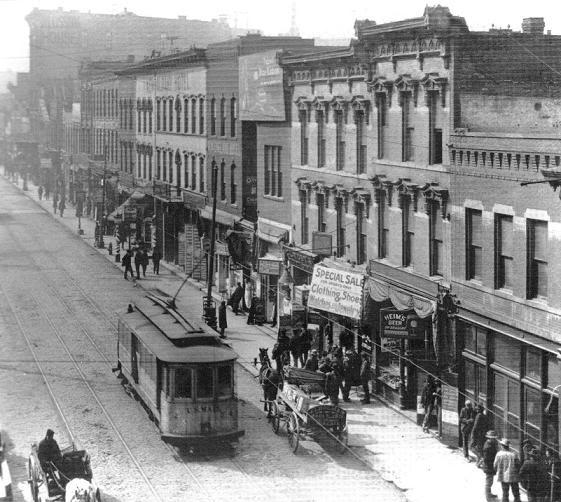

Activity and commerce have defined the West Bottoms since before the surrounding city existed. Originally known as the “French Bottoms,” French fur trappers developed the land at the convergence of the Kansas and Missouri Rivers in the 18th and early 19th centuries. They set up semi-permanent residences on the land as they traded with Kansas Indians. With the advent of steam power, the West Bottoms became one of the busiest receiving ports in the Midwest. Steamboats traveled upstream on the Missouri River and offloaded goods and supplies for those traveling westward or trading with Mexico along the Santa Fe Trail system.

Following further technical advancements of trade and travel, the dawn of the age of the railroad spurred more development in the district. Established in 1871, the Kansas City Stockyards made Kansas City (and its famous strips of steak) an important city for meat industry, second only to Chicago, whose Union Stock Yard & Transit Co. processed more meat per day than any place in the world. The bottomlands experienced a serious economic boom centering on the stockyards.

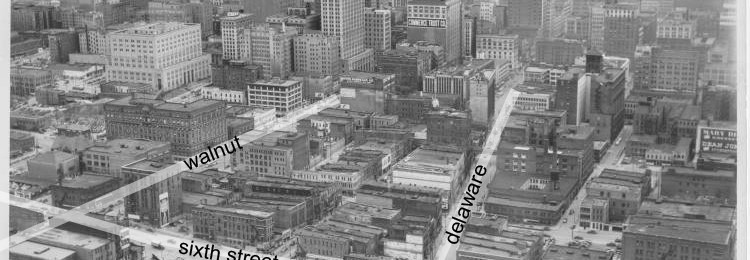

In 1871, Asa Beebe Cross designed the new Union Depot, built parallel with the bluffs on Union Avenue, and at the time, claimed the title of the largest building west of New York. Hotels such as the Pendergast Exchange—a combination saloon, boarding house and hotel—popped up on every street in the district, and restaurants and taverns thrived in the prosperous environment. Ninth Street became known as the Wettest Block in the World with 24 out of 25 of the buildings on the street housing saloons. By the turn of the century, nearly 90 percent of the overall value of Kansas City came out of the freight, meat-packing, agricultural and industrial commerce of the West Bottoms.

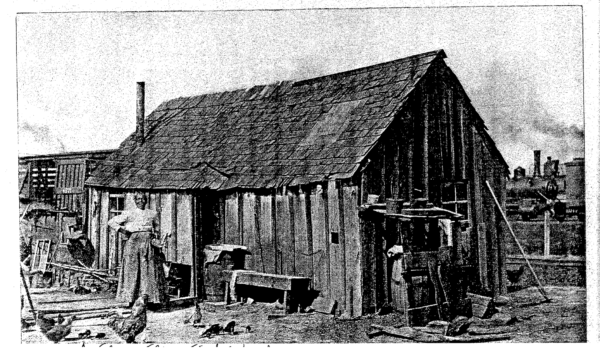

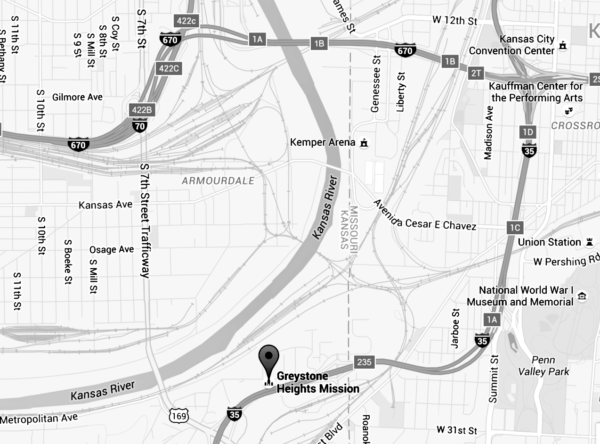

Despite the prosperity brought on by the district, not everyone who lived there was looked upon auspiciously. Cut off geographically and culturally from the rest of Kansas City, the neighborhood of Toad-a-Loop in the West Bottoms developed a unique and controversial identity. Even the occurrence of the community of Toad-a-Loop caused speculation. While the rest of the Bottoms had been built on land incorporated by either Kansas City, Kans., or Kansas City, Mo., Toad-a-Loop existed in a sort of geographical limbo claimed by neither Jackson nor Wyandotte Counties. According to the article “The Demise of Toad-a-Loop,” published in 2001 by The Historical Journal of Wyandotte County, the neighborhood was “the horseshoe area surrounding Greystone Heights with a portion crossing over into Jackson County, Missouri” and was “noted for criminal gang activity for over 25 years until about 1905.”

The neighborhood of Greystone Heights (the small Kansas community Toad-a-Loop literally “loops” around) influenced how Toad-a-Loop developed into a community. Greystone Heights sat on a hill, which geographically formed during the last Ice Age. This occurred as the Kansas River and its tributary, Turkey Creek, shaped the topography of this part of the city. Glacial deposits then formed the mound of earth that would eventually become known by locals as “Greystone Heights” in homage to its elevation. As this portion of land set in between the West Bottoms on the Missouri side and the Armourdale/Rosedale neighborhoods on the Kansas side boomed in population at the turn of the century, people moved east and northeast—crossing into Missouri. This made not only the technical residency of the people living there ambiguous, but also made any illicit activity that might take place there just as difficult to counteract as it was often disputed whose criminal jurisdiction those in Toad-a-Loop fell under—a situation that would eventually be exploited by some of the neighborhoods less-than-upstanding residents.

Greystone Heights also helped the Toad-a-Loop neighborhood adopt its unique moniker. The true origin of the name is somewhat lost (with even its spelling up for some debate.) “Toadoloop” became more popular throughout the early to mid-20th century, but some theories persist that argue against that name. One such theory, again, comes from the geography of the local waterways. The neighborhood lies along the loop formed by Turkey Creek feeding into the Kansas River and, as the story goes, somewhere in the center of this circle used to stand some sort of large landmass or mound of what was probably limestone and bore a striking resemblance to a toad. As such, it became known as Toad Hill and Toad-a-Loop came to be as a corruption of Toad-of-the-Loop.

Another theory, found in an article written by journalist Purd B. Wright for the Kansas City Star Magazine in 1925, states, “One of the troublesome place names in Kansas City is that of Toad-a-Loop, the bottoms southwest of the city proper.” He goes on to cite common theories of the time claiming that “the accepted story of its origin is that frogs abounded in the ponds there…” Because of this, Irish immigrants working as switchmen in the bottoms dubbed the neighborhood “Toadoloop” or “Toad-a-Loop,” depending upon whom you asked. However, Mr. Wright is quick to point out that, while this theory persists, “an Irishman never would have said Toad-a-Loop.”

Probably the most likely origin story, which also comes from Mr. Wright, is not Irish, but French. Back in the very early days of the 19th century, when Kansas City was a hotspot for French fur trappers and traders, the high bluff that formed in the center of the loop-in-question was famously known by trappers to be home to large numbers of wolves (among other creatures). The semicircle around these bluffs became known to them as “Tour-de-Loup” or “the walk of the wolf.” “Loup” actually being the French word for “wolf” and not loop, as might be otherwise assumed. However, as the story goes, eventually Loup became Loop and Tour became Toad by non-French-speaking Kansas Citians.

Regardless of the origin of the neighborhood’s unusual name, it would go on to be well known throughout the metro for much more than that. Aside from it being a neighborhood in which those who worked in the slaughterhouses and stockyards lived, Toad-a-Loop, for a brief few years between the 1890s and 1903, was also widely known as a place where the many bars and gambling halls were rough—and the people were rougher. At its height it was said that there was a one saloon per every three residences. And although this number wasn’t much different from the bar-to-resident ratio for the rest of the West Bottoms (the stretch from James to State Street on Central Avenue, for example, contained 14 gambling houses and 15 bars along the two-block stretch) what made it different was the “tough element” in the area. Toad-a-loop became the haven for those who, because of racial, ethnic, or other social status issues, were kept from patronizing a “better” class of taverns and card games.

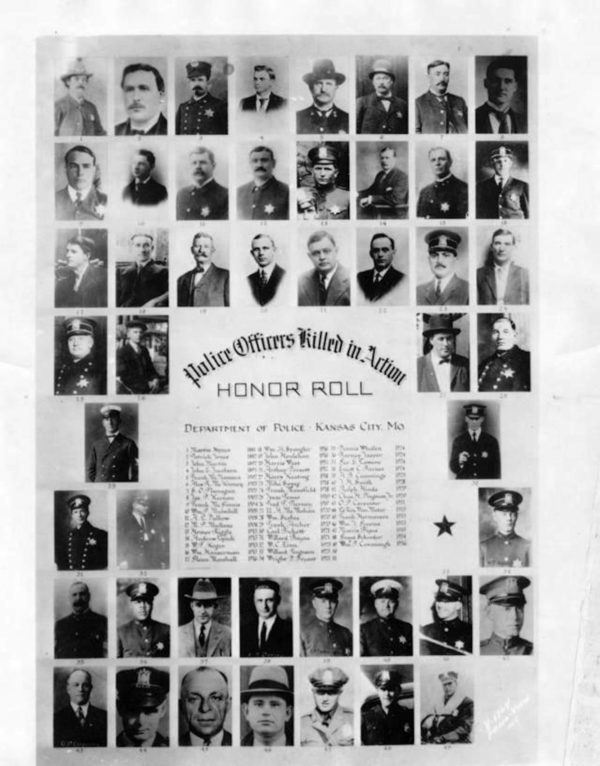

Perhaps no better story epitomizes the nature of the neighborhood during these years than that of the killing of detective John W. Gilley in 1889. A man known only in the records now as “Smith” killed Gilley in court. By 1889, Gilley had made a name for himself in the Bottoms, particularly in Toad-a-Loop, for breaking up the many street gangs that ruled the neighborhoods surrounding the district. He was one of few Kansas City, Kans., officers willing to work alongside their Missouri counterparts to help keep criminals from taking advantage of the jurisdiction issue to avoid arrest. As such, he’d earned the ire of many criminal outfits working those areas. When “Smith,”a member of a particularly notorious gang, the “dirty dozen gang,” found himself in court for burglary connections in Kansas, Missouri, Nebraska, and Colorado, he also spied Gilley there and managed to stab the detective in the neck, resulting in his death in the hospital several days later.

Notoriety surrounded the Toad-a-Loop neighborhood, but its existence was short lived. Railroad yards (the Santa Fe Railroad from the West and the Missouri Pacific from the East) took up all of the available real estate in the neighborhood though the late 1890s. The final blow struck in 1903 when a devastating flood forced many residents to relocate, which made much of the West Bottoms, and especially the poorest communities such as Toad-a-Loop, essentially non-residential.