The Jewelry Box

Public Park, gardens, beauty spot, Ewing Kauffman, George Kessler, City Beautiful, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

On the northern bank of Brush Creek, a block south of Kansas City’s Nelson-Atkins Museum, the Kauffman Memorial Garden rises 30 feet above the floodplain. Seen from the east side of Rockhill Road, the 8-foot limestone walls surrounding the garden conceal all but the tops of a scattering of blue spruces and the roofs of two structures, off-center. Approaching the place for the first time, a walker might see these walls as the boundary of the fabled city on a hill, or a city-state in miniature.

In the summer of 2009, I was a new father, a teacher with an ocean of time. So I strolled with my 10-month-old daughter, Audrey, and looking where she looked, I explored the city from a new perspective. Before fatherhood, the garden site might have generated only a curious glance while driving; its two acres of rock, shingle and evergreen no doubt blurred past without notice. It took walking, a mode of discovery as old as our species, for the Kauffman Memorial Garden to lure me inside its walls.

Audrey and I had been searching for a flock of more than 100 Canada geese. We tracked their movement by following grass-green droppings east along Brush Creek walkway in Frank A. Theis park; beneath the Oak Street Bridge, about 15 yards from the squatters’ pallet camp, we spotted the flock strutting along the hillside like nomads beneath an ancient city wall. There the garden stood, with the sun climbing the eastern quadrant, lighting on an upper, shimmering tier of vine, leaf and bumblebee. Wheeling Audrey along the edge of the flock toward the southern wall, I found an entrance through the limestone. A sensory thud of flower and leaf, limestone and water shook me. By the time we rolled to a stop, the essences of the place returned to their things. The fountain lifted eight tines of water within an octagonal basin; behind the entrance of a greenhouse stood giant, potted orange trees, whose uppermost fronds peered out from behind glass panels framed by a blue-green shingle roof; along the inner wall to the right was a bronze Italianate sculpture fountain; in the open spaces to the left, vines threaded a pergola, which shaded two benches and four chairs; and just beyond the fountain, yellow-orange zinnias, purple alliums and multi-stemmed trees and shurbs defined the red-brick walkway that channeled us between two limestone brick gazebos toward the water thrum and flower bursts of a second garden room.

The path opened onto brass dancing girls, like Degas’ ballerinas, each arranged 10 feet apart along a rectangular pool. When Audrey leaned forward in her stroller and smacked her thighs, I stopped and set the brakes so she could watch the dancers collect the play of sunlight and fountain spume onto their brass bodies. A photographer’s beeps and clicks cut through the haze of my wonderment. He leveled the camera’s giant lens at a tall, sherbet-orange lily and triggered a beep and several automatic shots. The orange perennial image might have been since, for all I know, brightening his living room these last three winters.

We strolled between plantings with nameplates: “Japanese Umbrella Pine” and “Gold-Leaved American Elderberry”; “Landini Asiatic Lily” and “Chicago Boxwood.” This latitudinal dissonance of faraway place names in close proximity, though pleasant, undercuts the symmetry of the hedges, flowers and trees lining the redbrick pathway. Throughout the garden, the visitor notices another, longitudinal dissonance created by the place: The high walls minimize the natural world to tall boxes, opening onto sky. The visitor finds his or her horizontal distances reduced to leaf and flower backed by limestone, and the sky above the garden’s wall filling with oak limbs and passing clouds. On this day, the garden took my daughter and me into its design and made us forget about time. The austere order maintained by the garden’s inner walls and walkway—like the gardens planted within fortified castles turned baroque palaces in 17th century France or Germany—kept the erratic world of the city out of view.

We then passed through a second entryway, and two black-marble headstones surprised me: “Ewing Marion Kauffman” joined with “Muriel McBrien Kauffman.” Two initial thoughts needed unraveling: (1) The Kauffmans’ gravesite offers the community a semi-public sarcophagus for two influential citizens; (2) The Kauffmans offer Kansas City a world-class garden, which, like the city itself, imposes a platonic order onto nature. The sun lifted my thoughts, like the rosebush climbing the gravesite wall, upward. If the headstones surprise people wandering along the walkway, then the gardens’ thrum of water on rock, bee on flower, and wind moved through trees might become, for them as well, an unexpected tribute to the spirit of great Kansas City visionary planners, philanthropists and architects.

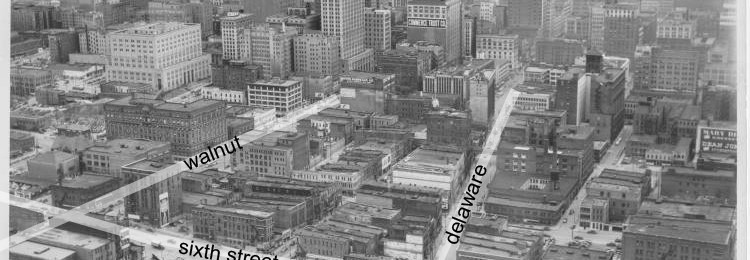

That summer, my seventh in Kansas City, I spent evenings on our porch reading the history of these neighborhood streets in Rick Montgomery’s Kansas City. His book helped frame the garden’s story as I pushed up Rockhill Road, past the east side of the Nelson-Atkins Museum’s sculpture garden. The story begins at the southern terminus of a specific place and time in Kansas City, circa 1890s through the 1930s, the decades in which the city’s architects rendered the late-19th century vision of The City Beautiful from a series of two-dimensional maps into a real start for what might have become the Midwest’s next great metropolis.

Kansas City developed southward with the rising popularity of the automobile and the vitality of the suburban home, and here at the southern end, a new stretch of storefronts and front porches rose along Brush Creek Valley, a terrain so rippled by hills, bluffs and creek beds that earlier developers considered it spoiled by Mother Nature. When George E. Kessler, Rockhill Nelson, August R. Meyer and Delbert J. Haff and other Kansas City visionaries looked out across the land in and around Brush Creek Valley, they watched a utopian cityscape materialize that would provide not only low-density neighborhoods, business and civic amenities to the families of the mason, store clerk and lumber baron alike, but also tree-lined parkways and boulevards, colonnade apartment buildings with balcony views of curvilinear streets, and fountain plumes amid flower gardens. These men dreamed a suburban dream harder to actualize than constructing scenic vistas, however. Instead, they pictured this new section of the city as one kept in harmony with neighborhood spirit, a code phrase denoting a communitarian way of life, one in tune with nature and humanity. “One of Kessler’s foundational legacies,” explains Paul L. Knox in Metroburbia, USA, “is the ideal of public space in which man and Nature could achieve a state of balance amid pastoral and picturesque settings and the conviction that the central mission of urban design is to promote beauty and amenity.” Over the years, Kansas City visionaries transformed the city’s muddy roads and shanty towns southwest of downtown into an interlocking system of wide boulevards and modern neighborhoods, made scenic with landscaped parks, such as Frederick Law Olmsted’s Swope Park (twice the size of Central Park) and unique public spaces such as the 1914 Union Station Kansas City, and the 1922 Country Club Plaza, which opened along a mile of Brush Creek Valley. The Plaza connected its fountain-lined boulevards to Kansas City streets, and crowds of motorists drove in to park, shop and dine. Seven years later, the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art opened its tall neoclassical doors atop a hillside overlooking the valley.

Born in Kansas City in 1916, Ewing Kauffman would contribute to making The City Beautiful Movement a reality, and he would carry this legacy onward until his death in 1993. After returning from World War II, Kauffman started a pharmaceutical company, Marion Laboratories, first operated out of his basement with an investment of $5,000. The company showed revenues of $930 million in 1988, the year before it merged with Merell-Dow Pharmaceutical. Kauffman’s philanthropic beginnings originated with two simple tenets: (1) “Those who produce share in the wealth,” and (2.) “Treat others as you would want to be treated.” Early on, Kauffman started investing in programs to help disadvantaged youths go to college, learn how to start businesses and improve their communities. In 1966, he established the Kauffman Foundation, a philanthropic think-tank devoted to advancing entrepreneurship and promoting education for the youth in America’s inner city. Now, with an endowment of $2.1 billion, the Kauffman Foundation ranks among the country’s 30 wealthiest private foundations. Each year, the foundation awards grants of $20,000 to 15 doctoral students. The foundation also gives its annual Ewing Marion Kauffman Prize Medal for Distinguished Research in Entrepreneurship, which amounts to a $50,000 award for one researcher. Another Kauffman Foundation initiative, referred to as BDH (Bureau Data Highlight), collaborates with the U.S. Census Department to gather data regarding startup companies’ contribution to overall economic health during cyclical downturns since the 1980s; another initiative, the Entrepreneurship Research and Policy Network, offers an online social network and database for authors and readers.

Over the next couple of months, and over the whole of that summer, Audrey and I included the garden in our goose hunting routine. Along with the ability to speak, Audrey had developed a renewed interest in the geese. Since noticing six or seven goslings one Saturday, she would mention them often. “Ze baby geesh,” was all she had to say to prompt a walk to see them. The goslings hatched in late May, in a nest the mother had made between a hydrangea bush and the wall’s exterior, explained the garden’s horticulturalist, Duane Hoover. Hoover admitted he had been watching the mother goose and her goslings along the south side of the garden as he pruned the blue spruces and trimmed vines earlier in the day. “When the creek flooded after last week’s storm,” he said, “I worried they’d been swept away.”

When I emailed him for this story, I asked about the Kauffman Garden’s dual roles as gravesite and public space. “Ewing and Muriel did not plan the garden to be their gravesite,” he says. “They came two years after opening.” Originally buried at Marion Labs in a courtyard, workers exhumed Ewing and Muriel Kauffman’s bodies and moved them to the Kauffman Garden site a month after the drug company was purchased in 2002.

“I consider the space here to be a private garden, privately funded, privately owned and everything,” Hoover explains, “yet it’s maintained to stay open to the public as a gift to the city from the Kauffman family.” Few make the connection between burial site and almost-secret gift to the public, he explains. A few years ago, however, an elderly woman approached Hoover to say that the garden reminded her of a jewel from her grandmother’s jewelry box. “Just walking through our gates,” says Hoover, “reminded her of opening the box and seeing all of the pretty things contained within.”