The Golden Age of Steamboating

City Market, guided tours, exploration, interactive exhibits, all-ages, gift shop, Lawrence the Mule

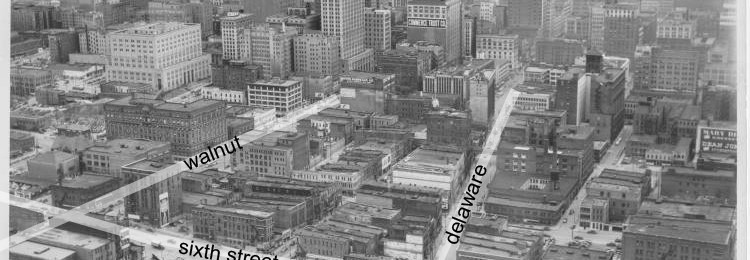

It took one visit to the Steamboat Arabia Museum just south of the Missouri River in Kansas City’s oldest neighborhood, the River Market, to confirm a lifelong suspicion of mine: money and booze make the world go ‘round.

After the Steamboat Arabia sank in 1856[1], the promise of both inspired three consecutive excavation teams to don waders and take to the Missouri River in hunt of buried treasure. The prize? Four hundred barrels of the finest Kentucky bourbon, believed to be buried with the rest of the wreck under the silt and shifting waters of the Big Muddy[2]. The bourbon alone was enough to inspire investors like the Tobener brothers—wealthy Kansas City tobacco men—to fund the project. But after a few test digs in 1877 returned nothing but bolts of ruined cloth and beaver felt hats—no booze barrels in sight—they abandoned the quest.

Archaeologists of the world take note: if you need funding for an excavation, tell the public there might be bourbon down there.

It took a new breed of treasure hunters to finally unearth Arabia over 100 years later. The Hawley family, Kansas City natives and owners of a mom-and-pop HVAC company, teamed up with Jerry Mackey, owner of the Hi-Boy drive-in[3] in Independence, MO. The team dug down into the topsoil hoping to strike it rich. Over 200 tons of cargo disappeared with the wreck, mostly brand-new goods bound for general stores or new frontier settlements out West. As the Hawleys’ dig started to return more and more of these artifacts, however, the talk turned from padding their bank accounts to filling in history. Once the team unearthed a barrel full of intact Wedgwood china, it was settled. They had to open a museum. Arabia’s treasures were too precious to hoard.

The team didn’t know much about preservation at the time, but they knew they had to act fast. As pieces of the wreckage came up, they went right into Jerry Mackey’s freezer at the Hi-Boy, alongside the ice cream and french fries.

Their technique has improved over the years, and the artifacts have a much more glamorous home at the museum’s 400 Grand Blvd. location in the River Market, close to the river that started it all. One of the more memorable parts of the museum’s tour is watching workers preserve and de-oxygenate artifacts in a lab right in front of you—with 200 tons of cargo to restore, their work still hasn’t finished. You can’t touch the artifacts, for obvious reasons, but they will let you try on a spritz of some French perfume found among the cargo. “It smells like my grandmother,” my lone tour companion remarks. I inhale the floral-sweet scent myself. Given Arabia’s timeline, more like great-great-grandmother.

When you walk in to the modern metal-and-glass-front building today, you might not realize you’re walking into a museum. The gift shop at the entrance has the usual generic souvenir chotchkies: rooster-themed wall art, I <3 KC shot glasses, plastic keychains with your name[4]. But, as your tour guide leads you down winding passages underground you’re transported back into the Golden Age of steamboating—when boot pistols were commonplace, mustaches were unironic, and the West was virgin territory, waiting to be charted[5].

Like excavators who would search for their cargo years later, Arabia’s passengers were awfully fond of the hard stuff. One of the most fascinating collections in the museum features the “medicine” of choice for the Westward bound. Dr. J. Hostetter’s Stomach Bitters seems a particularly popular brand—if the “active ingredients” don’t cure what ails you, the 90-proof alcohol surely will. A series of bottles labeled “Unknown Chemicals” sits on a shelf nearby. “They sent those bottles to a lab once,” our tour guide confides, “And they sent a note back that said ‘If we tell you what’s in these, you won’t be able to keep them.’ Probably opiates,” he offers, grinning. I get the impression he doesn’t get to tell too many school groups about this.

The semi-guided tour is the only way you can experience the Steamboat Arabia Museum, but it’s worth it for the expert commentary while you check out Arabia’s hull or touch the 7-foot snag[6] that brought her down. The tour guides are genuinely enthusiastic about Arabia’s history and the work they’re still doing to preserve her. They leave you some time to explore on your own, and kids (and kids-at-heart) will enjoy the interactive displays that let you pump the boat’s old steam engine and turn her two-story-tall paddle wheel.

The treasure-hunting spirit that drove the Hawleys to dig seems mirrored in Arabia’s passengers, many of whom were heading out in 1856 to explore new frontiers. As a result, the museum has an infectious, kid-like zeal for exploration and discovery. It helps that Arabia’s wreck isn’t a tragedy. No cause for somber remembrance here: all the passengers made it safely off the sinking steamer. Almost. The skeleton of Arabia’s only victim remains on display in a gleaming glass case: a stubborn old Missouri mule the team affectionately calls “Lawrence.”