The Best Of: Major Mayors of Kansas City

Judge James Cowgill, John Bailey Gage, H. Roe Bartle, Charles B. Wheeler, Rev. Emmanuel Cleaver II

Kansas City politics have never been boring. From early days of contention between Union sympathizers and secessionists, to the torrid era of the Pendergast Machine, the mayors of Kansas City have often been strongholds in the middle of a shitstorm. Here’s a sampling of some of the most interesting and influential mayors in Kansas City history:

Dr. Johnston Lykins, M.D. (1853-55): The first legal mayor of City of Kansas, Dr. Lykins overtook William Samuel Gregory, who was ousted for not technically being a citizen. As mayor, Lykins built the city’s first schoolhouse and absorbed acreage to the south, what is today considered the downtown area. Before his political career in Missouri, Dr. Lykins had served a spiritual one in Kansas, working as a Baptist missionary to the Potawatomi tribe. Though Lykins was a Union man, his second wife, Martha Livingston, was banished to Clay County for her Secessionist sympathies. She returned to further influence Kansas City history by marrying artist George Caleb Bingham and opening a home for Confederate orphans, which continues operation today as Little Sisters of the Poor.

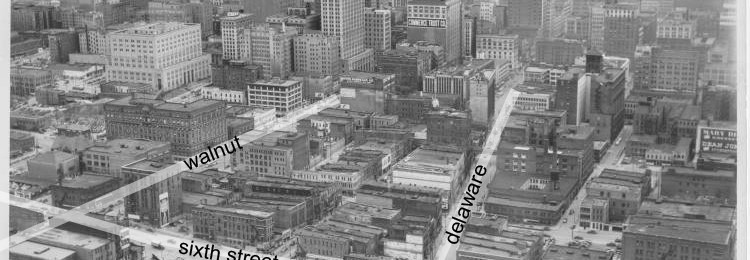

Col. Milton Jamison Payne (1855-60): Called “the Father of Public Improvements” and reelected five separate times, Payne was a prominent and impactful mayor. He helped modernize Kansas City with its first sewers and the Missouri Gas Company. Payne pushed for development on Main Street up the previously dreaded “incline,” laying roads up to 29th Street. The youngest mayor—only 26 upon first election—Payne also fit in the time to invest in the city’s first newspaper, The Enterprise, and the burgeoning railroad business.

Col. Robert Thompson Van Horn (1861 & 1864): Van Horn was a prominent Republican at a crucial time of the Civil War, ultimately leading his own battalion in the Battle of Westport. His most notable contribution to the development of Kansas City was fighting and winning as a congressman to bring to Kansas City the first bridge to span the Missouri River. He served as a postmaster, an alderman and a state legislator. His newspaper the Journal was an important tool for promoting public improvements. He lived a long life at his property, Honeywood, where a reunion of living mayors met for his 90th birthday. The Honeywood estate in Independence is now the site of Van Horn High School.

Major William Warner (1871): His short term was marked by much bigger influence, as he advocated the first stockyards, a public library, and an extension of the city limits. He was self-taught and self-made as a boy in Wisconsin before earning a law degree at the University of Michigan. Warner continued to practice law throughout his political career, all the while exuding public appeal as a champion for Kansas City progress. He had a hand in promoting the Industrial Exposition, held on fairgrounds constructed at 12th and Campbell, which hosted a parade that included, by reports, about half of the city’s 40,000 residents. Warner later served as a U.S. district attorney, and then a Republican U.S. Senator in 1905. His Quality Hill home, constructed in 1880 at 1021 Pennsylvania Ave., remains standing today.

Henry Christian Kumpf (1886-88): Elected mayor three times, and serving in various other positions in city management, German-born Kumpf had an impressive impact on his adopted Kansas City home. He came to the area in 1865 and opened a billiard hall, then worked his way up through civic positions until his 1886 election. During his third term in 1888, the “City of Kansas” adopted a new charter and officially became Kansas City. Under his leadership Lincoln High School opened, the Art Institute was founded, construction began on New York Life building, and Kansas City entered into a real-estate boom.

James Monroe Jones (1896-1900): A mayor of myriad accomplishments, James M. Jones helped push an ever-industrializing Kansas City into the 20th century. In his first term, Jones got the troubled waterworks service under city control and sealed the deal to create Swope Park. In his second term, Jones made the city’s first long-distance telephone call, received by Omaha mayor James Dahlman. He was also instrumental in the annexation of Westport. Though widely lauded for his accomplishments, Jones did have his enemies: a dispute over the terms of the Metropolitan Street Railway with attorney James A. Reed led the men to a stockyards brawl. Reed replaced Jones as mayor in 1900, and Jones moved to Indianapolis.

James A. Reed (1900-03): A happy accident of timing, James A. Reed’s mayoral election coincided with the rebuilding of the burned Convention Hall in time for the Democratic National Convention. Overseeing a cooperative effort of fundraising and labor, Reed was able to take credit for the speedy three-month reconstruction—an act which led to a rallying cry of the “Kansas City Spirit.” Reed read the welcoming address at the convention, only heightening his public profile. His presence on the national stage would grow later with his three terms as a U.S. Senator, in which he played an influential role granting Missouri the distinction of having two branches of the Federal Reserve Bank.

Jay Holcomb Neff (1904-05): Jay H. Neff was a newspaperman before he was a politician, and the editorials published in his Daily Drovers Telegram often influenced local happenings: the 1901 piece “Call it the American Royal” had a clear effect on the Kansas City Livestock Show. Revered for his piousness as a public servant, Neff respectably gave all of his mayoral salary to charity. His son, Ward Andrew, eventually donated Neff’s estate to help build the University of Missouri School of Journalism in honor of his father. Neff Hall continues to house the renowned institution today.

Judge James Cowgill (1918-21): With the tragic distinction of being the only Mayor to have died in office (quite literally, from a heart attack while seated at his desk in City Hall), Cowgill served a term also marked by global unrest. Cowgill was in office during a great West Bottoms fire and the influenza epidemic. The wildfire spread of Spanish Flu was thought to be attributable to rampant kissing between local girls and Army trainees. The outbreak of Spanish Flu killed 1,865 Kansas City residents in Cowgill’s first year as mayor. But that torrid 1918 also included Armistice Day, leading to the construction of the Liberty Memorial.

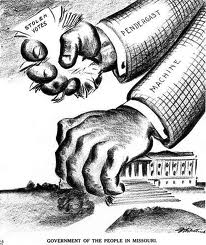

Bryce B. Smith (1930-38): Smith’s father was a baker and the young Bryce learned about business and management in the family shop. His rise to the top was less wholesome: Smith’s mayoral career, while prosperous, was defined by the influence of the shadowy Tom Pendergast. Smith served for five terms during the tumultuous 1930s. He positively impacted through involvement in the Ten Year Plan—the construction initiative that gave rise to the new City Hall and employed thousands during the Great Depression. That program depended on a contract with Pendergast and his concrete company. The Boss Tom also influenced Smith’s blind-eye to the rampant drinking and crime bubbling in the city’s underbelly, a trait that garnered public outcry after the bloody 1933 Union Station Massacre.

John Bailey Gage (1940-46): The precocious Gage entered the University of Kansas at age 16. He graduated cum laude from the Kansas City School of Law only six years later. He took office for his first of three terms in 1940, as World War II was brewing and the city had run corrupt and bankrupt. After Tom Pendergast was jailed in 1939 for tax evasion, it was revealed just how deeply Kansas City had fallen into debt. Gage entered office with no individual political ambitions, simply a bipartisan plan to restore sanity in City Hall. Gage trimmed fat in municipal services and corrected the dishonest hiring practices of the Pendergast era. He was lauded for cleaning up the city and catapulting it about $20 million out of the hole.

H. Roe Bartle (1956-62): With a reputation for riveting oratory skill and a busy social calendar serving on boards of directors, the politically inexperienced Bartle had little problem winning over Kansas City during his election and term. Serving from 1955 to 1963, Mayor Bartle had a role in the city’s desegregation, throwing weight into struggles at local hospitals and in the police department. His memory lives on in name: the Convention Center adopted his likeness for Bartle Hall, and the football team he brought to Kansas City bears his nickname—“the Chief.”

Charles B. Wheeler (1971-79): Charles B. Wheeler was elected mayor in 1971, with an international vision. Wheeler had an influential role in the construction of the expanded airport in the quickly developing northern suburbs. He aided in the development of the Truman Sports Complex, giving a flashy new home to the city’s professional sports teams. His term also saw the construction of the Crown Center shopping complex and beloved theme park Worlds of Fun. With such prosperous development, Wheeler’s era was later called “the last Golden Age of Kansas City” by local magazine Ingram’s. Wheeler would go on to serve in the state senate, and as a lifelong champion of Kansas City progress.

Rev. Emmanuel Cleaver II (1991-99): The first African-American mayor, Emmanuel Cleaver began his public life in Kansas City as a commanding minister at St. James United Methodist Church. A lifelong activist against prejudice in his professional career, Cleaver brought this sensibility to his position, appointing more people of color to municipal roles and implementing stricter equal protection laws. His term was noted for his interest in urban improvements, with attention to infrastructure and youth development programs. A stretch of 47th Street was named for him shortly after his tenure ended, now colloquially known as “Cleaver Two.” Cleaver continues to represent the region in the U.S. House of Representatives.