Pacific House

Architect: Asa B. Cross

401 Delaware Street, Kansas City, MO 64105, USA

Built in 1861, but rebuilt and expanded in 1868 after an 1867 fire, the Pacific House Hotel was considered the finest in Kansas City until the real estate boom of the 1880s. At the turn of the century, it still retained its stature by acquiring the nickname "Palatial Pacific."

Frank and Jesse James were said to have played billiards and lounged at the bar. From 1861 to 1865, the Union Troops occupied the hotel. From its lobby, General Thomas Ewing issued his infamous Order No. 11, which forced evacuation of property on anyone who could not prove their loyalty to the Union. This order was considered one of the harshest and cruelest measures of the American government against its people. Properties in Jackson, Cass, Bates and Vernon counties in Missouri were burned to the ground, animals stolen, and many families left with nothing. The goal was to stop Pro-confederate “guerillas” from finding provisions or shelter in the countryside. All hay and grain was removed from fields or burned. Some innocent civilians were stranded without shelter or food and others were still not safe even after evacuating with their wagons and leaving their homes. Wagon after wagon was looted and many families killed. This scorched-earth military policy ultimately had an inverse outcome from what was intended.

Since 1999, the Pacific House has offered 32 affordable residential units.

Askew Saddlery Building

213 Delaware Street, Kansas City, MO 64105, USA

Before Kansas City was the “heart of America,” it was the Wild West. The Askew Saddlery building reminds us of our cowboy past. Built in 1892, the brick factory served the prominent Askew leather goods company. Brothers William and Wilson Askew partnered with nephew Frank when they arrived in Kansas City after the Civil War. Their leather business grew, and by the 1890s the Askew saddle was synonymous with a quality cowboy product. The business thrived with the nearby stockyards, as traveling ranchers bringing their beef to market stopped over at the Askew’s for the finely crafted leather saddles. The former factory was converted into the Askew Lofts in 1993—the first big residential redevelopment project in the River Market.

Coates House Hotel (Quality Hill Apartments)

1005 Broadway Boulevard Kansas City, Mo 64105

Originally named the Broadway Hotel, the Coates House Hotel was the finest hotel of its time and was once nicknamed “the hotel of the presidents.” Kersey Coates, namesake of the hotel, arrived in Kansas City in 1854 with a desire to help develop the land that was then mostly pasture. His most significant accomplishments were in the Quality Hill neighborhood wherein the Coates House Hotel was built. Designs and building plans for the opulent Broadway Hotel (later named Coates House Hotel) halted during the Civil War when the Union army claimed the hotel for barracks. Before the hotel was built, Union soldiers from Fort Leavenworth established horse stables on the foundation in order to protect Kansas Citians from an invasion by William Quantrill.

Eventually, the war ended and the community recovered. A wealthy neighborhood began to grow around the hotel, which offered a luxurious stay to such famous guests as Grover Cleveland and Theodore Roosevelt.

A fatal fire destroyed the south side of the Coates House Hotel on January 28, 1978 resulting in the most loss of life by fire in the history of Kansas City.

George M. Shelley Dry Goods Co.

308 Delaware Street, Kansas City, MO 64105, USA

George M. Shelley came to Kansas City from Kentucky in 1868 and quickly became known as “the merchant of Delaware Street.” Ten years after his arrival, in 1878, the 29-year-old man became mayor of Kansas City and served two terms. The site now houses The Glam Room.

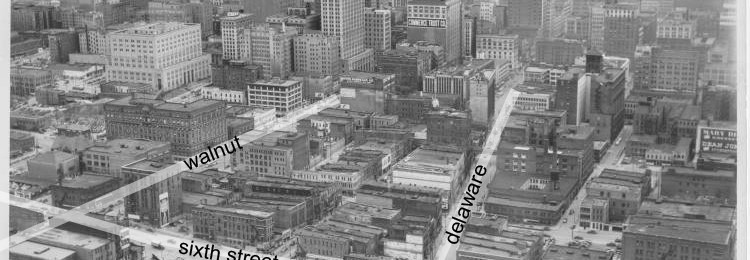

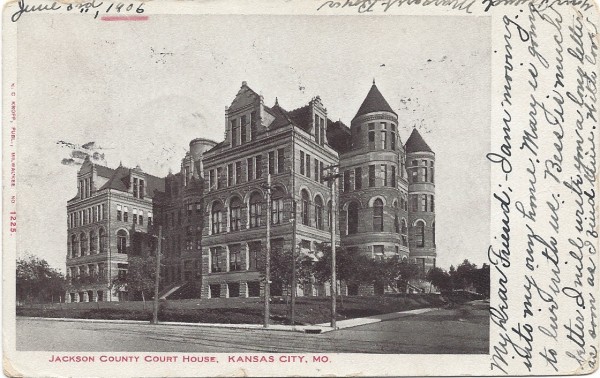

Old Jackson County Courthouse

Main Street & East 2nd Street, Kansas City, MO 64105, USA

The original courthouse began as a hotel in 1868 at Second & Main Streets. Courthouse construction took over when the hotel ran out of money before its completion. Destroyed in a tornado in 1886, the country courthouse was forced to take up residence on the corner of Delaware and Fourth Streets. In 1892, the second courthouse was built at Missouri and Oak Streets, where it remained until 1934 when it relocated, again, to its present-day location at 12th and Oak Streets in downtown Kansas City.

Old St. Patrick Oratory

Architect: Asa B. Cross

806 Cherry Street, Kansas City, MO 64106, USA

Old St. Patrick Oratory, the third Catholic parish established in Kansas City, was built in 1875 and is the oldest Catholic building in continuous use today. A passionate project of Father James A. Dunn and a community of about 200 families, the Baroque brick building was erected to serve the Irish community on the east side. The congregation and building interior have gone through many evolutions and near-extinctions since this humble beginning, threatened by freeway construction and a changing church. The distinctly historic building was severed from the diocese in 2005, now serving as an oratory for traditional Latin mass.

Board of Trade Building

Architect: Asa B. Cross.

Wyandotte Street & West 8th Street, Kansas City, MO 64105, USA

Established in 1856 by a group of merchants looking to exchange grain, the Kansas City Board of Trade rose to a place of prominence in Kansas City’s history of economic growth. The original building, completed in 1877, was called the Armour Bank Building, with the trade hall located upstairs. The Trade capitalized on Kansas’ hard red winter wheat, the primary component in bread-making. The Board of Trade moved once before establishing its current location on the Plaza in 1966. As of June 2013, the Board of Trade’s once-bustling face-to-face grain exchange has been bought and moved to Chicago.

Volker Place Building

6 West 3rd Street, Kansas City, MO 64105, USA

The namesake of the William Volker & Co. picture frame shop was much more than an average business owner; he was philanthropy personified. William Volker, a German immigrant with low funds and high ideals, settled in Kansas City in 1882. He grew his business—specializing in picture frames and window shades—and by the early 1900s was influencing the city from his position on the Board of Pardons and Paroles. Volker didn’t stop there: in the early 1910s he pioneered a Board of Public Welfare, targeting urban poverty with social programs. Though Volker’s project was a casualty of political disagreement before the end of the decade, this model would go on to influence broader welfare programs around the country. The old shop on 3rd Street has since been converted into apartments, but still bears the beloved benefactor’s name.

Bunker Building

Architect: unknown

820 Baltimore Avenue, Kansas City, MO 64105, USA

The Bunker Building, built in 1881, housed the Western Newspaper Union, which was considered “one of the most important enterprises” in Kansas City during the turn of the century. Founder George Joslyn of Iowa teamed with former Kansas City Journal members (and KC real-estate moguls) Walter A. Bunker and John McEwen to create a Western Newspaper branch here in the heart of Missouri. The company rose to greatness as one of the largest printing suppliers in the country - boasting more than 400 Midwest newspapers as clients. Later, Walter Bunker purchased the Kansas City Journal, and Western Newspaper moved to its own building on 10th Street. The original headquarters held at 9th and Baltimore features an array of stylistic elements, combining Victorian, Gothic and Romanesque designs.

Wood's Building

107 West 9th Street, Kansas City, MO 64105, USA

Mr. James W. Wood sought an architect (unknown) to erect his namesake building - speculatively for investment purposes. It became office space for many accomplished Kansas City doctors, including a rarity in Dr. Martha Dibble, one of the few female physicians in a male dominated industry. The lady doctor was a pioneer, and Grinnell College’s Dibble Hall is a monument to her and and husband Leroy. Martha also cofounded and drew up the constitution for the Kansas City Athenaeum, now the city’s oldest running women’s club.

The Wood’s building was also the second home of local prominent printing business, the Lane Blueprint Company.

In the 1880s, entrepreneur Joseph Cosby relocated from his native Kentucky to Kansas City, acquired both the Wood’s Building and its next-door neighbor, the Wright House Hotel, merging them into one as the new Hotel Cosby in 1889. The hotel almost saw the wrecking ball until a local trio restored it in 2014. Milwaukee Delicatessen Co., named after a restaurant and bar original to the building in 1908, occupies the ground floor; and Sasha’s Baking Co., serving sweets and wine and beer.

Thayer Building (Bracken Building)

Architect: Walter C. Root (Chicago)

820 Broadway Boulevard, Kansas City, MO 64105, USA

The Thayer building is a four-story, red brick, stone and terra cotta, Victorian Eclectic style building. Broadway Boulevard developed into a thriving commercial avenue in the 1870s and the early 1880s. Two of the original buildings from this period include 935 Broadway and the Thayer Building at 820-822 Broadway. It is currently owned by DST Systems, Inc., that opened its headquarters in Kansas City in 1969. DST is a major proponent of living and working in downtown Kansas City, Mo.

Kansas City Dime Museum

110 West 9th Street, Kansas City, MO 64105, USA

Soon after Kansas City claimed Abraham Judah, a Cincinnati-transplant known as “the best liked showman in the West,” he found famed as the pioneer for theatrical activities in Kansas City. Upon relocating to Kansas City, he brought with him a single attraction–the Wild Man of Borneo. After he took over management at the Dime Museum at the corners of 9th and Delaware Streets, the museum hosted exotic theatrical shows such as “Zella Zubalon Cirasscian,” “James Wilson, the human balloon,” and “Sig Franco, the stone eater.” “[The museum hosts] refined and first-class stage performances in theatorium,” Judah claimed. “Everything is first-class.” The Sporting and Theatrical Journal, published in the 1880s out of Chicago and edited by Charles C. Corbett, included notes on weekly circus happenings and museum stage performances, and often discussed Kansas City’s own Dime Museum.

According to the journal’s coverage of the Kansas City Dime Museum for the week of March 22, 1884, the following shows were to take place:

“Kansas City Dime Museum–Attractions for coming week are Prof. De Jalma, the Mammoth Fat Boy, Harry Eads and the Albino Children, concluding nightly with the very funny musical comedy entitled “Snowed In.”

New York Life Insurance Building (Catholic Center)

Architect: McKim, Mead & White

20 West 9th Street, Kansas City, MO 64105, USA

An example of impressive design by nationally renowned architecture firm McKim, Mead & White, the New York Life Building brought a level of prestige to Kansas City as downtown’s first skyscraper. Upon its completion in 1890, the building’s 12-story tower soared over the neighboring structures. It was the first time New York capital had been spent in Kansas City, and at a cost of $1,000,000 it was quite an investment. The New York-based company’s investment in Kansas City was a vote of confidence for the up-and-coming Western metropolis. Its striking brownstone façade still exudes a vision of class over Baltimore Avenue. The identifiable bronze bald eagle statue still perches atop the grand arched entrance. The Catholic Diocese obtained the building in 2010, and have since renamed it the Catholic Center.

New England Building

Architect: Bradlee, Winslow and Wetherell, three highly esteemed Bostonians

112 West 9th Street, Kansas City, MO 64105, USA

The New England Building was built during the substantial development years of Kansas City’s downtown business district as a “show of faith” from Eastern investors. The building was built for the New England Mutual Life Insurance Company from Boston, Mass. The New England Safe Deposit and Trust Company and the New England National Bank rented space within the building. Architecturally significant because of its Renaissance Revival style, the building boasts a two-story oriel window with carved stone panels at the base that bear the seals of the five New England States: Maine, Dirigo (I direct) with pine tree and deer; New Hampshire, the frigate Raleigh with 13 stars in a circle below; Vermont, a shield and the motto Freedom and Unity; Rhode Island, the motto Hope above an anchor; Connecticut, three grapevines with the motto Qui Transtulit Sustinet (He who transplanted continues to sustain).According to the National Registrar of Historic Places, the New England Building is ornamented with “Renaissance motifs such as swags, wreaths, rope molds, urns, cherubs and formalized plant forms predominate.”

Each floor has two safes; and 57 fireplaces dot the interior. The Federal government took over the building for Social Security offices and painted the interior “government brown,” until it was purchased by Faultless Starch Co. in 1968 and restored to its heavy oak woodwork.

St. Mary’s Episcopal Church

Architect: William Halsey Wood

1307 Holmes Street, Kansas City, MO 64106, USA

The “Mother parish of Kansas City” boasts not only 31 beautifully stained glass windows, but also a rich and fascinating history. The oldest Episcopal church in Kansas City began as a small parish in 1854 under the name of St. Luke’s. The new church building’s (still in use today) construction was completed in 1887 and officially opened for services in 1888. Victorian/late Gothic stylistic detail combined with a red brick veneer proffer a stunning building on Holmes Street. William Halsey Wood - architect and designer of St. Mary’s - incorporated many items from the old parish into the new interior of the structure, such as original wrought iron hanging light fixtures and a giant wooden cross. Any building suffers deterioration, but a lucky grant in the late 1950s saved the church from demolition and restorations began. The parish contributed greatly to the cause of the poor, hungry and ailing, laying the foundations for All Saints Hospital, which we now know as St. Lukes Hospital. The altar within the church is dedicated to Reverend Henry David Jardine, the parish’s first rector. It is believed that his spirit hangs around the building to this day!

Gibraltar Building

Architect: Van Brunt & Howe

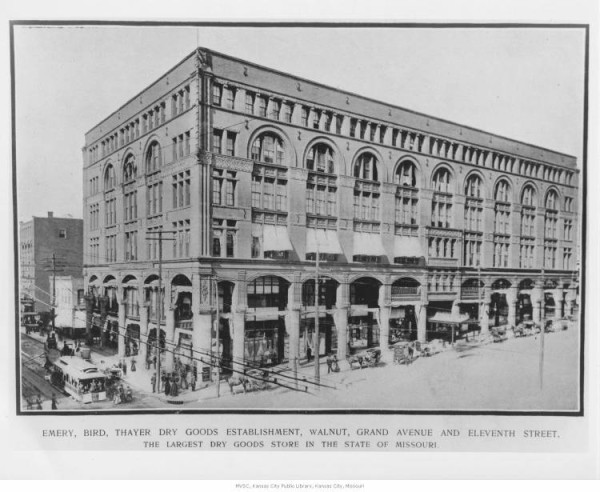

Van Brunt & Howe, a prominent architectural firm in Kansas City during the late 1800s, designed some of the city’s most impressive – and unfortunately, razed– buildings, like the Emery, Bird, & Thayer department store and tearoom and the Gibraltar building.

Today, if you pass by 818 Wyandotte Street, it’s nothing but a tar-paved parking lot. When the Gibraltar building opened in 1888, the spot looked, oh… a little bit different.

And my, the publicity the Gibraltar building (and Kansas City itself) attracted that year! Though the saying goes: any publicity is good publicity, a murder in the brand-new building definitely turned off some prospective office tenants.

Savoy Hotel and Savoy Grill

Architect: S.E. Chamberlain and Van Brunt & Howe

219 West 9th Street, Kansas City, MO 64105, USA

John and Charles Arbuckle of Arbuckle Coffee Co. built the hotel’s original wing in 1888, which crowns the Savoy the oldest running hotel west of the Mississippi. The original owners were the first in the nation to sell roasted coffee in one-pound bags, saving customers the step of roasting green coffee beans themselves. During prohibition, City Boss Tom Pendergast delivered trucks of frozen chickens, their cavities stuffed with bottles of gin, whisky and rum, to The Savoy Grill, Kansas City’s oldest restaurant, established in 1903.

Builders and Traders Exchange Building

Architect: Knox & Guinotte

612 Central Street, Kansas City, MO 64105, USA

A rare example of High Victorian Italianate style architecture in the wholesale and garment district downtown Kansas City, Mo. Originally built in 1889 for the Builders and Traders Exchange, in 2005, 612 Central St. became the flagship building for the Atriums Lofts complex.

Exchange Hotel

303 West 8th Street, Kansas City, MO 64105, USA

Built during the burgeoning commercial wholesale district in the late 1880's spanning Broadway Boulevard to West 8th and West 7th Streets, this three-story brick building is still in excellent condition.

Emery, Bird and Thayer Building

Architect: Van Brunt & Howe

Emery, Bird and Thayer became the king of “Petticoat Lane” – the nickname for the shopping district surrounding it. The company began in 1846 as Coates and Bullene, then became Bullene & Brother, and then just plain Bullene, followed by Moore, Emery & Co and finally settling as Emery, Bird and Thayer in a brand new building at 11th and Walnut streets – they’d already outgrown two prior locations.

The original building façade touted red brick and pink sandstone; an addition was made in 1900 and the building received a fresh coat of cream and gold paint. An impressive row of clocks hung above the first floor elevators showing times in major cities around the world (fun fact: after the Pearl Harbor attacks during WWII, the Tokyo clock was removed). Up the elevator one would find Emery, Bird and Thayer’s famous Tea Room, where anyone might have a spot of the drink, and the company even hosted tea parties for the city’s children.

Ebenezer Building

309 Delaware Street, Kansas City, MO 64105, USA

Originally housing the William W. Kendall Boot and Shoe Company, this five-story red-brick building with its three terra cotta gables was known for ladies shoes. The Ebenezer addition was built to house a paper company.

Burnham-Munger Manufacturing (S.A. Maxwell Co.)

Architect: Walter Root

614 Central Street, Kansas City, MO 64105, USA

Pillars of Kansas City, Mo.’s, garment district, partners James Burnham and Willis Munger, operated multiple businesses in the area, including BM Manufacturing, Burnham Hannah Munger Dry Goods Co. and Burnham-Munger Manufacturing. Philanthropist Burnham held the director’s post in the city’s Commercial Club, sat as commissioner of the Park Board and founded another dry goods company in Detroit, MI.

The five-story red brick manufacturing plant building on Central Street once housed 700 sewing machines, its workers producing pants, overalls, shirts and rompers. Burnham and Munger created Fitz Brand work clothing, the zero-collar flannel shirt, and Aladdin rainproof cloth (for hunting), all of which were exclusively fabricated in Kansas City.

After Burnham-Munger vacated the Central Street plant, Illinois-based S.A. Maxwell & Co. moved in. Founded in 1833, the company manufactured and sold a variety of stock, including wallpapers, paints, hardware, even endeavoring into publishing for a short time.

Today, Atriums West calls 612 Central St. home., with an open, central atrium, and featuring 41 residential units for sale and lease.

Lyceum Building

Architect: George Mathews

106 West 9th Street, Kansas City, MO 64105, USA

The asymmetrical ornate structure on 9th Street features Chicagoan stylistic elements in its steel-frame design. Commissioned by the Missouri, Kansas, and Texas Trust, the building served as ticket office for the Kansas City, Pittsburg, and Gulf Railroad Company. Later known as the Kansas City Southern Railroad Co., the rail line ran from Kansas City, Mo., to Port Arthur, Texas. The line further evolved into a direct route to the Gulf of Mexico, promoting and enabling commerce in foreign markets.

The Missouri Republican Club took up residence in the building in 1901. Also within the building prevailed the majestic Lyceum Hall—home of many Kansas City elite social events and glamorous balls—and even a horse show and auction in 1896.

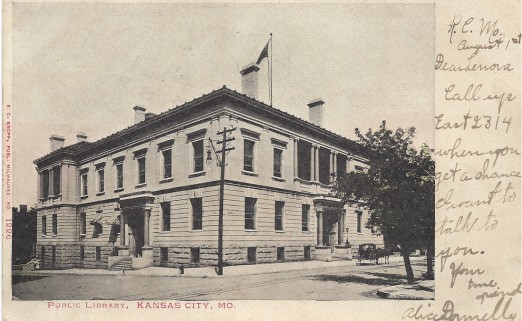

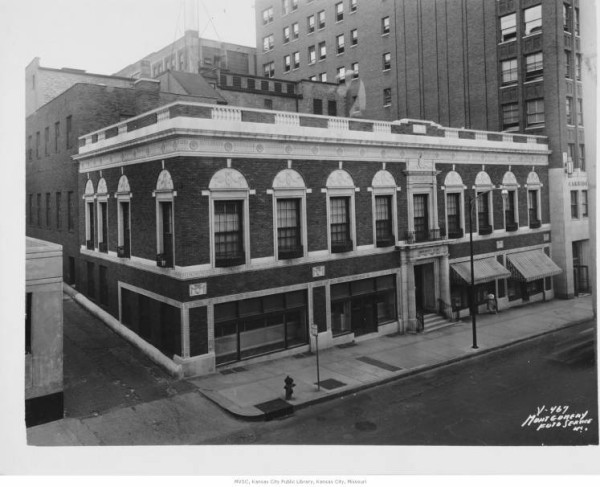

Public Library Building

Architect: Hackney & Smith

500 East 9th Street, Kansas City, MO 64106, USA

Ninth Street in Kansas City was a major artery at the end of the 19th century. The growing metropolis demanded an outlet for cultural and intellectual development. Thus, the library’s construction at 500 E. 9th St. began in 1895 and was completed in 1897. Texas granite, 36 inches thick, formed the ground story, and the Second Renaissance Revival style structure boasted nine chimney stacks, Ionic and Doric columns throughout, and an impressive marble fireplace in the rotunda on the main floor. Though designated a rotunda by the architects (Hackney and Smith), the area is neither a dome - or even round! An addition to the building in 1917 literally doubled the floor space, and even more extensive remodeling in the 1930s made it a state-of-the-art institution. The structure itself is fireproof and even contained a ventilation system to blow hot or cool air as needed. The library was not only a leader in modern construction, but other areas as well. The Kansas City Public Library was possibly the very first in the entire country to add a children’s installment. The library fostered what would later become impressive and integral institutions in the city: The Nelson Atkins Art Gallery and the Kansas City Museum of History and Science.

William Rockhill Nelson donated a small art collection to this library, where it remained on display until it relocated to the Nelson estate, which turned into the Nelson-Atkins Art Museum. In the 1960s, the library outgrew itself and relocated to12th and McGee; and then again to its final location on West 10th Street where it still thrives today.

Barton Brothers Shoe Company Building

Architect: Shepard and Farrar

609 Central Street, Kansas City, MO 64105, USA

The land previously occupied by Seamans and Benedict – makers of the classic Remington typewriter – was acquired by the Barton Brothers Shoe Company, and the six story brick building (originally five, with a later addition) that still stands today saw completion in 1896. The Barton manufacturing plant was located on the nearby corner of 8th and Washington Streets. The Barton Brothers company – who also produced hats and other garments - owned several buildings in the heart of the wholesale/garment district of Kansas City, MO., which spanned West 7th to West 10th Streets and Washington to East Central Streets.

This historic district was a hub of production (manufacturing overalls, rompers, hats and furniture – to name a few) from the late 1800s to the mid 1900s. The architectural styles of the structures in the area reflect the time span. The city boasted such a large output that it was said one of every seven garments purchased in the United States originated in Kansas City – both in design and manufacture.

The Barton Brothers building, located just where Wyandotte and Central Streets merge into one (hence the double address), would later be purchased by Vista Construction Co. and RHW Co., along with the old Trade Exchange building and the Burnham-Munger-Root Dry Goods Co. building. The pioneering companies converted the structures to lofts, which unfortunately saw little demand at that time. A reconversion in 1989 (a mere three years later) resulted in the Historic Suites of America Hotel, a luxurious inn catering primarily to extended-stay guests. The hotel remained in business until 2004, at which time the companies transformed the buildings again when the demand for loft living finally arose in the city, turning 609 Central into its present-day incarnation: the Atrium Condominiums.

Butler Standard Theater (Folly Theater)

Architect: Louis C. Curtiss

300 W. 12th St. Kansas City Mo 64105

The Folly Theater was designed and built in 1900 by architect Louis S. Curtiss. Curtiss wanted the theater to be a “spectacle of lights,” and as theatrical on the outside as the inside. With most of the city homes still powered by gas, a building lined with electric lights on the exterior became quite the spectacle. When the theater was in use, a giant illuminated globe would descend a poll on the exterior of the building. The theater opened on September 23, 1900 with “The Jolly Grass Widow,” a burlesque event starring Madame Diks.

Armour-Volker Building

Architect: William Rose

310 West 8th Street, Kansas City, MO 64105, USA

Named for two of Kansas City, Mo.’s most influential individuals and families, the Armour-Volker building is situated in the heart of the wholesale (or garment) district. As a noted philanthropist, William Volker advocated social welfare and garnered the nickname “Mr. Anonymous” due to his habit of donating large sums of money to organizations – you guessed it – anonymously. Born in Germany, then relocating to Chicago and finally settling in our city, Volker developed countless institutions, organizations, and businesses. Not only did Volker design and implement the “first modern welfare department in the United States” (the Kansas City Board of Public Welfare), he also had a major hand in creating a research hospital, and the University of Kansas City (now University of Missouri at Kansas City [UMKC] located on Volker Road). He also funded the purchase of the land for building the Liberty Memorial (a towering tribute to veterans which houses the National WWI Museum on 26th Street).

The Armour name refers to the distinguished wealthy family who greatly impacted Kansas City for generations. Charles Watson Armour, Vice President of the Armour Packing Company (creators of a multi-million dollar meat packing industry in Kansas City) and William Volker were both donors to the local Wheatley-Provident hospital, a facility aimed especially at treating African-Americans in an era of segregation and disparity in medical care.

Plotsky Investment Company—a successful business established by the Plotsky brothers, Herbert, Robert and Jack—were mainstay tenants at the Armour-Volker at 306-308 W. 8th St. Father of the Plotsky gang, Louis, was a savvy businessman himself, and founded the local Kansas City Boys Wear Manufacturing Co. On the fifth floor of the Armour-Volker building you could find the Talon Inc. Zipper Manufacturing Co. The zipper company, founded in 1893, was the largest zipper supplier in the world. Finding a booming industry in the wholesale/garment district of Kansas City, Talon set up their regional facility in the Armour-Volker building in 1956.

Converted to the SoHo Lofts Condominiums in 1987, the Armour-Volker building has deep roots in this historic district.

Dwight Building

Architect: Charles A. Smith, 1903; McKecknie and Trask, 1927

1004 Baltimore Avenue, Kansas City, MO 64105, USA

Mr. Steven N. Dwight, described as having “a frankness of cordiality,” saw a magnitude of success in Kansas City’s future. A wealthy banker, Dwight invested in multiple Kansas City real-estate endeavors, owned the water works operation in Galena, Kan., and added his namesake 10-story, ornate all-steel frame structure (the first in the city!) to his empire in 1903. Unfortunately, Dwight passed away the following year. In 1904, his widow, Mrs. Della Dwight, took ownership and hired none other than the savvy Joseph Bruening. Bruening was the financier of the nearby Board of Trade Building, chairman of his J.A. Bruening Company, and owner/operator of a myriad of Kansas City buildings. Bruening just so happened to be married to Della Dwight’s niece - also named Della!

Willis Wood Theater

106 W. 11th St. Kansas City Mo 64105

Willis Wood Theater opened on August 25, 1902 with a performance by Amelia Bingham and her New York-based company. Willis Wood sought to bring the most opulent and ornate theater to Kansas City after the Coates Opera House burned. He spared no expense in the theater's construction at the northwest corner of 11th and Baltimore Streets. The exterior was said to resemble that of a colorful wedding cake made from yellows, reds and greens.

After 15 years of success, a small fire started in a 5th-floor dressing room and made its way to the stage area where it burned up to 15 rows of seats before the night watchman alerted the fire fighters. They were able to save the exterior shell of the Willis Wood Theater, but nothing else. It was razed in 1918 and replaced by the 20-story Mark Twain Building, which still stands today.

Hess Carriage Company Building (Star Loft Building)

1700 Oak Street, Kansas City, MO 64108, USA

The building at 1700 Oak Street that is now called the Star Lofts was originally home to the Hesse Carriage Company, a transportation manufacturer that survived more than a century by the art of adaptation. It occupied this building from 1903 until 1946, but the Hesse Carriage Company had gotten its start in 1857 and would remain independently owned until 1996. In the early days, William C. Hesse got his start making wagons in Leavenworth, Kan., for the prospectors heading west for the gold rush. The Hesses had already made a presence in Kansas City by the time son Otto inherited the business, and started focusing on automobiles. From this building, the company experimented with weatherproof body design, and had great success adapting their wagons into delivery vehicles. Hesse Carriage Company produced the city’s first Coca-Cola delivery trucks here. Hesse helped on the home front during World War II, producing fire trucks for the military. But by the time they moved facilities in 1946, Hesse had redirected their attention to their specialty: cold storage vehicles for the soft drink industry.

Faxon, Horton & Gallagher Drug Company

Architect: Smith and Rea

718 Broadway Boulevard, Kansas City, MO 64105, USA

It may have since been dubbed the Eisen Building, and at present, the Fountain Lofts Apartments, but the brick beauty at 7th and Broadway will forever be remembered for its original tenants. The Faxon, Horton & Gallagher Drug Co was a widely successful Kansas City, Mo.-based business with a massive clientele in nearly all of the western states.

New York-native (and Kansas senator) James Clark Horton met Frank A. Faxon in Lawrence, Kans., where both had relocated. In 1878, the pair and a Mr. B.W. Woodward (the third cofounder of the company) moved to Kansas City, organizing Woodward, Faxon & Co. Woodward left in 1897, and it became the Faxon, Horton & Gallagher Drug Co. In 1906, Horton would retire; Horton was removed from the company name at that time.

The three were great friends. Horton, in his official resignation letter, typed, “I can hardly find words to express the high regard in which I shall always hold my friends, Mr. Frank A. Faxon and Mr. John A. Gallagher, with whom I have been so long and so pleasantly associated, each year only increasing my confidence and self-esteem.” Faxon and Gallagher amicably purchased Horton’s share of the company and continued a prosperous business producing toiletries, face creams and perfumes in the same building the three had had built in 1903.

Faxon became deeply involved in the Kansas City community. He cofounded the Kansas City Commercial Club, sat on the city’s council, and held the presidential position in the Wholesale National Drug Association. In his spare time, he advocated better conditions in schools and workplaces.

The Faxon, Horton & Gallagher Drug Co was committed to Faxon’s own personal motto – “Make Kansas City a good place to live in.”

Gumbel Building

Architect: John McKecknie

801 Walnut Street, Kansas City, MO 64106, USA

This fireproof, rectangular 56,000-square foot building was erected between 1903 and 1904 on Walnut Street. Architect John McKecknie employed a groundbreaking technique in his design. At the time, steel was the mainstay material used for building. The Gumbel building was one of the very first structures created with reinforced concrete in the United States. As the concrete hardened, it essentially built the support for the next level, resulting in a safer as well as cheaper method. The six stories feature incredibly ornate detail and unique terra cotta work with decorative Roman eagles and a lovely cornice on the 6th floor. It housed the training center for the US Naval Reserve, and hosted weekly training for the Coast Guard, Second District. “Some of the finest men of seafaring services come from the Midwest,” said the unit’s Lieutenant Commander, “and never see salt water until assigned to active duty.”

Hobbs Building

The Hobbs building was erected in 1904 as a furniture manufacturer. An advertisement from 1952 showed that the company’s address was still in operation, where one could purchase a two-piece living room set for $150, a three-piece sectional for just $90 and a platform rocking chair? You could have taken one of those babies home brand new for a mere $15. By the 1930s, a coalition called the Central Industrial District Association (CIDA) had formed to advocate for improvements in the area – in both private and public sectors – to keep it running smoothly. Interestingly enough, the CIDA headquartered for some time alongside the sectionals and rockers within the seven-story brick Hobbs building.

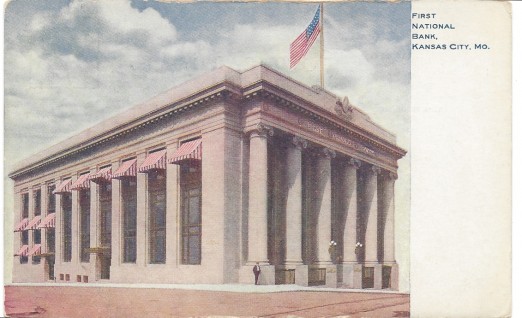

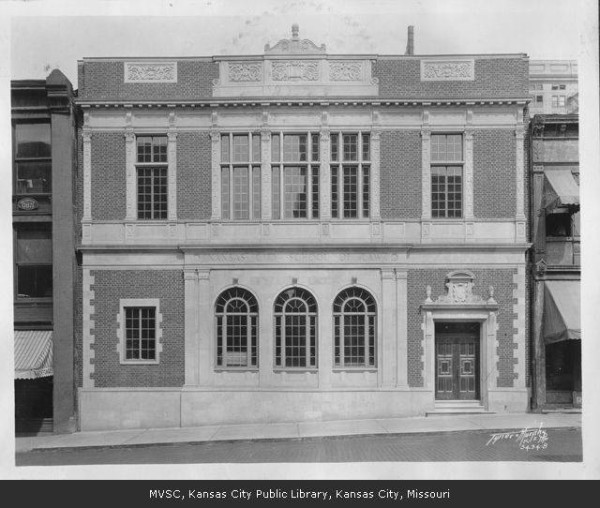

Kansas City Public Library, Central Branch (formerly First National Bank)

Architect: Wilder & Wight

14 West 10 Street, Kansas City, MO 64105, USA

Kansas City architectural firm Wilder & Wight built this stately structure in 1906 for the First National Bank. The building, with its austere columns and grand interior, became more of a relic throughout the 20th century. The First National Bank continued to use it as something of an anchor location as they metastasized to newer, taller, more modern buildings in the growing downtown. Since 2004, the building is now the Kansas City Public Library, Central Branch.

Lane Blueprint Company

Architect: unknown, circa 1905

906 Baltimore Avenue, Kansas City, MO 64105, USA

A talented architect presented Kansas City with the 3-story, Neo-Classical reinforced concrete building around 1905. Unfortunately, the architect remains unknown. The Delaware-based Camerograph Company (manufacturers of Photographic-Facsimile machines) were among the first occupants of 906 Baltimore St. Joseph G. Godwin, the chief chemist at Camerograph, was an alumnus of the University of Missouri. Other residents of the building included the local LaRue Printing Company (as its secondary location) and the Lane Blueprint Company, a successful print company still in operation. Though the company later relocated to the nearby Wood’s Building, it currently utilizes the original building for storage.

Argyle Building

Architect: Louis Curtiss

306 East 12th Street, Kansas City, MO 64106, USA

Original first-floor tenant was the Gate City National Bank. In 1914, Issac and Ike Katz purchased the ground-floor space and opened up a confectioner’s business. Due to new laws that required shops selling tobacco to close at 6 p.m., the Katz Drug Store hired a pharmacist and added medical products for purchase.

Home to businesses such as Gate City National Bank and Katz Pharmacy, the late Renaissance Revival Style building designed by Louis Curtiss was erected in 1906 in the Central Business district of Kansas City. Its intended tenants at 12th and McGee were various medical professionals, and later the building would house more than 50 practices at once. The building’s 10 stories of steel and reinforced concrete - topped with a penthouse—was expanded upon in the 1920s. Curtiss (along with fellow Missourian architect McKecknie) pioneered the reinforced concrete construction method in Kansas City and several of his structures throughout the city have been selected for the National Historic Registry, including the Boley Building and the Folly Theater. Most of the Argyle’s original structure and style remain intact. Katz Pharmacy, one of the main ground floor tenants, offered an eclectic array of product - the usual prescription drugs and over-the-counter meds, as well as appliances, groceries, produce, and even pets of exotic nature (like baby alligators!). It’s proprietors were nicknamed the “Cut-Rate Kings.”

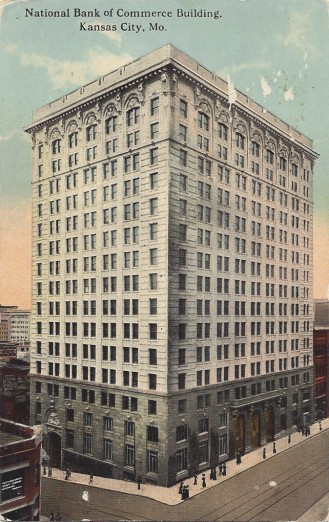

Commerce Trust Building

Architect: Jarvis Hunt

922 Walnut Street, Kansas City, MO 64106, USA

Generations of the Kemper family date as far back as 1906, when William Thornton Kemper was appointed the Commerce Trust Co.’s first president. Still to this day, William Thornton Kemper’s great-great-grandson, Jonathan Kemper, remains CEO and chairman of Commerce, Missouri’s largest bank. Constructed in 1965, the Commerce Tower, a 30-story building built to adjoin the original 922 Walnut location, stands as the ninth tallest habitable building in Kansas City. Harry Truman, along with 18,000 other Kansas Citians, signed the buildings last beam, put in place in 1965.

Scarritt Building

Architect: Root & Siemens

818 Grand Boulevard, Kansas City, MO 64106, USA

Built during a prosperous time for new Kansas City skyscrapers, the Scarritt Building is exemplary of the style influenced by renowned Chicago architect Louis Sullivan. Designed by local team Root & Siemens, the 11-story building is adorned with an intricate decorative façade surrounding the doorway. The interior is similarly opulent, with marble and mahogany ornamentation in the common areas and striking natural light. The Scarritt Building’s Grand Ballroom is still offered to the public for weddings and parties, but the designated office space is currently being considered for a redesign project that would turn the building into low-rent artists’ residencies.

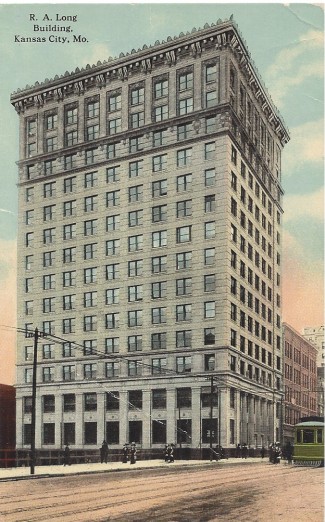

R.A. Long Building

Architect: Howe, Hoit & Cutler

Grand Boulevard & East 10th Street, Kansas City, MO 64106, USA

Built in 1906 to serve the needs of the growing Long-Bell Lumber Company, R.A. Long envisioned the tower as a statement skyscraper to enhance the developing Kansas City skyline. The nationally successful Long had an astute sensibility for the built environment, and his vision allowed for the first steel-structured skyscraper in Kansas City. This decision eerily predated the financial demise of the Long-Bell Lumber Company in the 1920s, as the architectural industry moved in droves to steel materials. The building’s mix of modern structural design and a classically styled façade had staying power, serving as the first home to the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City briefly from 1914 to 1921, and in this century, a home for UMB Bank.

Finance Building

Architect: Smith and Rea

1009 Baltimore Avenue, Kansas City, MO 64105, USA

This seven-story structure was designed by architectural firm Smith and Rea and erected in 1908, intended to house financing companies as well as the offices of their attorneys. The two-part vertical building recalls Commercial style, boasting terra cotta and granite materials. Charles A. Smith (of Smith and Rea) was a successful architect in the city, and commissioned independently again in 1923 for an eighth-floor addition. Over 100 years later, the building retains its original marble floors and now houses 32 residential lofts.

Frank T. Riley Memorial

This is not your average, run-of-the-mill giant orb tank emblazoned with the name of the town, as is more often than not the case. No, the Waldo Water Tower is a grand, ornate castle pillar, standing tall at an impressive 134 feet. The balcony parapet would be a prime spot for archers defending their keep, the height an advantage in case of attack. But it’s not a castle, and this isn’t the medieval times – imagination aside, it’s a defunct water tower -- only slightly less impressive. It sits on the National Register of Historic Places under the name of the Frank T. Riley Memorial. That’s who the city purchased the land from, Riley, an accomplished mason of the 32nd Degree and owner of a local publishing company producing mostly law briefs and the like. And upon this land the tall white tower arose, twelve-sided with 18-inch thick reinforced concrete walls. The design included ornamental arched windows – 12 of them, one for each side – opening onto a balcony. For whom was meant to enjoy the balcony is uncertain. Steep ladders and staircases offer an avenue to the tip-top, if one were courageous enough.

Boley Building (Katz Building)

Architect: Louis Curtiss

When Charles Boley, owner of Kansas City’s Boley Clothing Co., hired renowned hometown architect Louis Curtiss to design his new location, Curtiss delivered – in a big way. The result was astonishing, as Curtiss’ semi-Nouveau signature style inspired a building the likes of nothing observed in its time.

Just one other glass structure such as the Boley building had been attempted by 1909 in the United States; tragically, it collapsed in 1903. Curtiss employed a method called a metal-glass curtain wall, leaving six stories of a bright, dazzling legacy in his wake. Thousands of people visited the new Boley’s store at 12th and Walnut streets on opening day just to catch a glimpse of the awe-inspiring design.

Jenkins Music Company

Architect: Smith, Rea & Lovitt

Operating for a full century, Jenkins Music Company was founded in 1878 right here in Kansas City. Specializing in instruments and music printing, the success of Jenkins prompted a move to its headquarters-home on Walnut Street. The building debuted as a six-story structure in 1912 -- in 1932, Charles Smith (the senior member of the Smith, Rea & Lovitt firm), returned to add an eight story south additon and two more stories to the original anchor building. Where before, the Jenkins HQ held the retail space, wholesale and offices of the music company, the addition housed a broadcast studio and even a recital hall.

The buildings are intact and just as lovely today as upon completion in 1932; the architects employed a mash-up of materials, including black basalt, black and buff terra cotta, red brick and exposed concrete. The Jenkins Music Company building is under renovation, soon to become the Jenkins Music Company Lofts.

oak tower (bell telephone building)

Architect: Hoit, Price & Barnes

Formerly, or alternately, known as the old Bell Telephone building, Oak Tower is a 28-story shining white structure studding the blue sky. Utilizing a brand-spanking new kind of lightweight concrete called Haydite, the tower soars at nearly 400 feet tall. It was the very first building to apply the new material; an experiment that clearly succeeded. The Haydite addition was made in 1929, doubling the original height of the building. Its original inhabitor was the Bell Telephone Company (the precursor to Southwestern Bell), thusly it was fully fitted for "cellular, microwave and fiber optic communications," according to Missouri Valley Special Collections. In more recent years, it has served as office space for city matters, such as housing a branch for Missouri's Child Support Offices.

Chambers Building

25 East 12th Street, Kansas City Power And Light District, Kansas City, MO 64106, USA

The steel tower on 12th and Walnut Streets in downtown Kansas City, Mo., was preserved through the development of the surrounding Power & Light District, which would surely delight its namesake. R.C. Chambers had not lived in Kansas City for over half a century before the building’s 1915 construction. Chambers had left his hometown in 1850, headed west for California to find a fortune. Instead he happened upon quartz mining in Utah, and accrued some serious wealth before his death in 1901. His siblings in Kansas City used a $10,000 chunk of the estate to buy a plot downtown—then the highest real estate price tag in city history. The Chambers Building began as a five-story structure designed by noted Kansas City firm Smith, Rea, and Lovitt; then Charles A. Smith designed an additional seven for a 1923 addition. The office tower was converted into lofts in 2003.

Gate City National Bank (Ambassador Hotel)

1111 Grand Boulevard Kansas City Mo 64105

Gate City National Bank outgrew itself in the Argyle Building and built and relocated to 1111 Grand Boulevard in 1920, attracting the Women’s Club of Kansas City as tenants for its upper floors. The club, founded by Mrs. James M. Coburn, began with an effort to provide women a place to meet weekly and effect philanthropic, civic and cultural activites in Kansas City.

For decades, the club leased the upper floors from the bank.

The powerful ingenuity of the ladies of the Women's Club led to the development of a “Milk Station" in 1920, which saved 500 babies with 24,895 ounces of donated breastmilk.

Although the building saw years of abandonment followed by a heinous nightclub, Club Chemical--said to have such a "nasty reputation that Kansas City police weren’t even allowed to work there off-duty as security guards"--its distant past as a beacon of feminist and civic duty and its present-day incarnation as the sleek and welcoming Hotel Ambassador prove that every place certainly does have a story to tell.

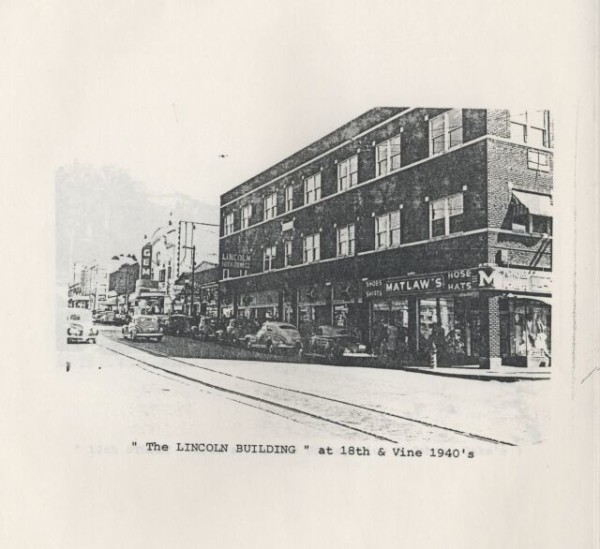

The Lincoln Building

Architect: 1921

the building heralded diversity in both clientele and business. Today it retains that diversity – though without the segregation – as a home to Danny’s Big Easy, “the Midwest Cajun restaurant,” a financial services firm, a tech company and the Black Economic Union of Kansas City, an organization established in 1968, focused on urban redevelopment and community. The Kansas City branch of the NAACP operates out of the Lincoln, a mainstay of the building for decades.

We shall not forget history, lest history forget us. The Lincoln Building “is a still-standing metaphor,” according the Historic 18th & Vine, “in regard to the type of self-sustaining community the segregated blacks of Kansas City had to facilitate for themselves.”

Jewell Building

920 Broadway Boulevard, Kansas City, MO 64105, USA

This low-rise brick warehouse built in 1921 is a member of the collection of buildings surrounding Broadway and 8th Street that make up the “Wholesale District.” Elected for historical preservation in 1971 and containing the more widely-known Garment District, this area boomed at the turn of the 20th century as Kansas City’s railroad position became increasingly desirable to industry. The Jewell Building housed George P. Ide & Co. shirt manufacturing company—one of the many textile production firms that would descend upon the warehouse buildings in the 1920s. Manufacturers of collared shirts, the George P. Ide & Co. brand reached its zenith of popularity with a print advertisement in 1922 by provocative photographer Paul Outerbridge. Historic New York auctioning house Christie’s sold the original print in 2000 for $314,000.

Cold Storage Building

Thanks to the expansion of the railroad system, Kansas City became one of the fastest growing cities in the country. This, along with Kansas City’s rich agriculture and beef industry with a need of refrigeration, caught the eye of the expanding Chicago-based United States Cold Storage Company. In 1922, the company hired S. Scott Joy to build a cold storage building at 500 E. Third St. in Kansas City and construction started in March of that year. By October, and after $1.5 million, which would be almost $20 million today, the 450,000 sq.-ft., six-story cold storage building (in other words, a giant refrigerator) was finished. In order to keep the building’s rooms cold, the walls were 13 inches thick and filled with cork. Then, cold saltwater pumped through 77-miles worth of piping to keep the building at, or below, zero degrees. The building also provided more than 100 tons of ice to local costumers. In 2005, the building became slotted for a mass $35 million renovation into 224 apartments. However, because the building was kept frozen for the more than 80 years while providing the agricultural and beef industries with refrigeration space, it had to be thawed for more than six months before the renovations could begin. Now, the building offers one-three bedroom apartments ranging from $575 to $1,300 a month.

McConahay Building

Architect: Nelle E. Peters

The McConahay building in Kansas City was adopted into the National Register of Historic Places for its exemplary tapestry-brick styling. Tapestry-brick “came in assorted colors, from purples, olive greens, and blues to deep russet and chamois with a rough finish, designed to catch the light and create a warm glow. These colors were meant to be alternated across a wall, imparting a decorative, patchwork effect (hence the name tapestry) throughout the finished building,” according to the Old House Journal. However, it is not only the building alone that is such a treasure in the city, but also its first residents. For the year following McConahay’s completion, one Laugh-O-Gram Studios occupied an office within. This studio was the product of a very young Walt Disney, where he first began creating animated shorts like Cinderella and Alice’s Wonderland, the very foundation of his later (and much more famous) Disney works.

University Club Building (Kansas City Club Building)

Architect: McKecknie and Trask

If seeking a bar, lounge, restaurant, library, and conference room all in one, welcome to the Kansas City Club (formerly the University Club) building at the corner of 9th and Baltimore. The prestigious private men’s club founded in 1901 relocated to the Neo-Classical reinforced concrete structure in 1923. Did I mention the squash court and the cigar stand? Unfortunately for the ladies, females were forbidden inside until the 1970s.

Pennbrooke Apartments

Architect: Nelle E. Peters, 1926

The Pennbrooke Apartment Building on West 10th Street is a proud addition to the National Register of Historic Places. In 1926, architect Nelle E. Peters completed the 66-unit, brick and stone Tudor Revival apartment building, each individual dwelling complete with a convenient kitchenette – a rarity, in that many multi-family structures shared a communal dining and kitchen area – and the kitchenette caught on as a trend. Pennbrooke Apartments was alternately listed legally as Pennbrook Apartments and Pennbrook Apartment Hotel. It’s unclear when exactly the “e” at Pennbrooke’s end became a permanent fixture, though likely it was around 30 to 40 years back. Pennbrooke is one of few buildings in Kansas City of the Tudor style whose façade remains intact and unchanged, even 90 long years later.

Kansas City School of Law

Architect: Wilkinson and Crans

Exhibiting multiple stylistic elements such as Chicagoan and Jacobethan, the building became home to the law school upon its completion in 1926. A unique institution in that its professors were practicing local judges and attorneys, its goal “was to build a great law school in Kansas City that would take rank with the leading law schools of the country.” The school emerged in 1895 from the minds of Edward Ellison, Elmer Powell, and William Borland - Borland being both dean of the school and a member of U.S. Congress. Indeed, many prominent law professionals originated from the school (including one Harry S. Truman, native Kansas-Citian and former U.S. President!), which merged with Kansas City University (now the University of Missouri at Kansas City) in 1938.

Carbide and Carbon Building

Architect: William A. Bovard

During the Great Depression, much of the United States suffered immense loss. Kansas City, however, kept on keeping on and managed to grow substantially in the era, both economically and in a barrage of construction - including the Union Carbide and Carbon building on Baltimore. The eleven-story (penthouse included) Art Deco structure commissioned by local real estate moguls William Hull, Barat Guignon and J. North Mehorney was first owned by Washington University (based in St. Louis). William Hull served as mayor of Weston (MO), his hometown, and is buried there in Graceland Cemetery. The savvy Hull also served as director of the First National Bank in Kansas City, as a United States representative for Missouri’s 6th district, and was a member of the Elk’s Lodge. Barat Guignon was the owner and president of his namesake KC real estate company. Involved in multiple real estate investments, North Mehorney also owned a structure at 11th and McGee streets.

The Waltower Building

Architect: Albert C. Wiser

823 Walnut Street, Kansas City, MO 64106, USA

While somewhat nondescript by today’s standards, the construction of the 12-story Waltower Building in 1929, built on the plot where the previous Ricksecker Building had just been razed, helped signal a significant era in the Kansas City skyline: we ranked eighth in the country for number of 10-story-high buildings. Among its first tenants were insurance companies, accounting and investment firms. The Waltower’s skyward optimism would be quickly crushed by the stock market crash that came later that year. The Waltower struggled to retain occupants during the Great Depression until a St. Louis-based company, Confero Paint Company, bought he building and within the same year gained full occupancy from local broadcasting companies, law firms and Mid-Continent Airline. Ownership of the building changed multiple times in the following decades. Luckily, the exterior remained largely unchanged, and the Gothic Revival design of architect Albert C. Wiser continues to be a stately—if relatively shorter—piece of the Kansas City skyline today. In 2005, it was converted into 53 luxury residential lofts.

National Garage

Architect: George E. McEntyre

Architect George McEntyre was so good at his profession, he managed to make a parking garage lovely enough in its Art Deco style to stand alongside the office buildings around it, integrating seamlessly. The National Garage – at the time of its completion in 1930, the largest garage in the city – had a capacity for 1,000 of those new-fangled automobiles amongst eight levels for parking and storefronts on the street level as well. McEntyre worked closely with Michigan-based engineer John Woolfenden to solve the parking-congestion problem arising in Kansas City’s business district during a construction boom – strangely enough, during the heart of the Great Depression. Kansas City was one of very few areas in the entire nation to actually see economic growth rather than devastation. Woolfenden designed a pioneering approach within National Garage, called the “Clearway Ramp System,” which utilized two separate ramp entrances – each one-way only to avoid collision -- similar to even the more modern garages today. National Garage was specifically intended for workers in the area and even more specifically, for workers at the Professional Building. McEntyre included a (not-so) secret below-ground tunnel from the garage to the Professional Building.

Bryant Building

Architect: Graham, Anderson, Probst & White

The 26-storied structure at 11th and Grand is actually the second Bryant building in Kansas City. The first was on the precise spot the newer one still claims; the original was a mere seven-stories and demolished for the erection of the high-rise office building. It was gifted to and named for Kansas City doctor John Bryant, when he married back in 1866. The new Bryant building took just over two months to complete construction -- to this day, perhaps, the quickest rising in the city's history. Though its erection was hasty, the planning was not -- the Chicago architectural firm of Graham, Anderson, Probst & White designed an Art Deco beauty built to last, as the Bryant continues to prove.

Board of Trade/Centennial Garage

Architect: Frank E. Trask

Erected by local architect Frank E. Trask (who also worked on the Board of Trade Building itself), the eight story brick garage served the Board of Trust members and employees. It’s the one and only Modernist building in the downtown Library District built after World War II. During the 1950s, Trask was again commissioned to add four more stories, and the garage then became known as the Centennial. Edwin Shields, president of local Simons-Shields-Lonsdale Grain Company, owned and operated the impressive 10th Street structure.

Trader’s on Grand (Kansas City Trader’s Bank)

Architect: Thomas E. Stanley

Trader's on Grand has a doozy of a history. Originally built as the headquarters for the Kansas City Trader's Bank, the institution soon merged with Kansas City Bank and Trust Company, becoming the Bank of Kansas City. The Bank did business for several years, followed by a short-lived company or two. In the early 1990s, the building housed the NationsBank, which also took part in a merger between itself and that old familiar Bank of America. They moved out in 1998, and the following year, a remodel was completed. As of 1999, the first owners of the impressive window-dotted structure were honored in name; 1125 Grand Boulevard was re-dubbed Trader's on Grand. The now-office building shelters doctors, dentists, law firms, the Jackson County Law Library and even the Silver Spoon cafe.

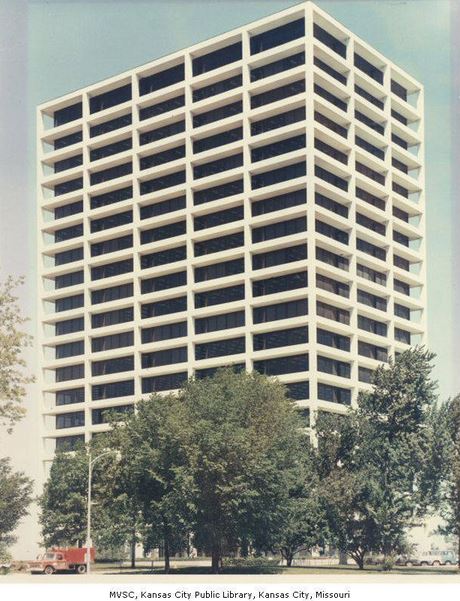

One Park Place (BMA Tower)

Architect: Skidmore, Owings & Merrill

The extravagant One Park Place condominiums that occupy the BMA tower today contrast heavily against the original design of the building, completed in 1963. Where the architects intentionally omitted ornamentation of the white marble and black-tinted glass facade, the renovation into One Park Place, opened in 2007, is antithetical to the simplicity of the modern architecture movement of the 1960s. Originally built as the Kansas City headquarters for the insurance company, BMA (Business Men's Assurance Company), the high-rise, 19 story office space perches atop the city's highest ground. Upon completion, BMA Tower won multiple awards (the First Honors Award and an award for architectural excellence) and was even featured in a Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art exhibit in New York. The tower's dedication drew a crowd of nearly 2,000 people. BMA occupied the marble monolith for nearly 40 years. Over time, the marble -- later revealed to be too thin to hold up -- deteriorated and in several places has been replaced by a glass-like material called neoparium, which is very similar to the white marble in appearance. In 2002, BMA sold the building and One Park Place began the restoration. These days, housed within the stark-yet-lovely structure, residents can soak in the indoor salt-water pool, store their wine in a temperature-regulated locker and tasting room, swing a golf club in the indoor driving range and even drop their pets off at the in-house dog-grooming facility.

richard bolling federal building

Architect: This building was a collaboration of four different architectural firms, led by Kansas City's Voskamp and Slezak. Everitt & Keleti, Radotinsky Meyn Deardorff and Needles, Tammen & Bergendorff also aided in the design.

The Richard Bolling Federal Building is the most capacious and largest of any other federal building in or around Kansas City. The 18-story soaring structure is named for Missouri House Representative in the United States Congress, Richard Walker Bolling. He was a beloved Congressman -- his time in office spanned nearly 30 years (1948 - 1972). As of late, the Bolling Federal building has undergone a complete and thorough restoration, with focus on energy efficiency and security -- think asbestos removal, yikes -- resulting in an eight-award-winning Class A office building. Class A is defined as "Most prestigious buildings competing for premier office users with rents above average for the area. Buildings have high-quality standard finished, state of the art systems, exceptional accessibility and a definite market presence." Well done, Bolling building. Well done.

commerce Tower

Architect: Keene, Simpson & Murphy

James Kemper Sr., both an active contributor to the revitalization of downtown Kansas City and the president of the Commerce Trust Company, envisioned a modern, soaring skyscraper for his new Commerce Tower on Main Street. Kemper and associates were adamant about employing a local architect for their design, and so it came to be that the firm Keene, Simpson & Murphy emulated the “glass-box” or glass “curtain” style of modern architecture’s pops, Mies van der Rohe. Alongside City Hall, the two buildings are the first skyscrapers in Kansas City designed by Kansas City firms.

Kemper wanted the tower to become “the middle west’s most distinguished office address.” Indeed, at the time of its completion, the 32-story (2 below ground) smooth glass monolith was the tallest office building in the state of Missouri, featuring amenities such as a lovely sunken garden off the tower plaza and a restaurant on the uppermost floors, divided into five sections of ethnic fare – and ethnic décor, to boot. Other original tenants to share the space with Commerce were a U.S. Post Office branch and barber shop.

The very last beam to be installed on Commerce Tower owns more than 18,000 signatures of locals and travelers alike, the most notable being our own hometown prez Harry S. Truman.

Mercantile Bank & Trust building (Wallstreet Tower)

Architect: Harry Weese & Associates

The Mercantile Bank and Trust building is an impressive, "glass-box"-style structure, exemplary of the Modern movement in architecture spanning the 1970s and spearheaded by the German Mies van der Rohe, who came to the States when Adolf Hitler took power. It boasts both excellent design and execution, and all of the telling elements of a period piece. However, the bottom of the tower is unaligned with the overall style, and creates a most fascinating illusion of an enormous floating black-glass building. Of course, it's very clever engineering behind the illusion -- the very thing that truly sets the Mercantile Trust building apart from its peers.

2345 Grand Boulevard (IBM Plaza)

Architect: Mies van der Rohe

The glass-paneled, modern-international building at 2345 Grand Boulevard has had many a name – and twice that amount of owners – in its near 40-year lifespan. An original partnership between the Mutual Benefit Life Insurance Company and IBM led to the rise of this ‘scraper; both companies inhabited the building. It’s interchangeably been called the IBM building, the Mutual Benefit Life Insurance building, the IBM Plaza – and today, is simply known as its address, the 2345 Grand building.

It was completed and in-business in 1975, the sleek design the hallmark of 2345’s renowned architect, Mies van der Rohe, hired by the first owners. The building deed changed hands several times, from the Shorenstein Company to Hines to the present owner, Franklin Street Properties, and today is the home of the state of Missouri’s Federal Immigration Court and Lathrop & Gage, a prominent Kansas City law firm.

City Center Square

Architect: Skidmore, Owings & Merrill

City Center Square was completed in 1977, dubbed a “vertical suburban shopping center” by Missouri Valley Special Collections. Its purpose: revitalization of Kansas City, in the midst of a downtown-spanning movement. Standing at 404 feet and 30 stories, City Center Square also exemplifies another movement of the period – the skyscraper. The upper floors house varying businesses and office space, as well as a post office branch, a private investigation office, conference rooms and even a gym. Though at the time of completion the expansive lower-floor food court and retail businesses were quite different, today, within City Center one can find anything from a cup of joe at Starbucks to the Indian-food quick stop, Curry in a Hurry.

One Kansas City Place

Architect: Patty Berkebile Nelson & Immenschuh

One Kansas City Place was originally proposed as part of a much larger project, Kansas City Place. Unfortunately, the project was never fully completed, with just two of the eight skyscrapers planned actually coming to fruition. One of the proposals, Two Kansas City Place, would have boasted an incredible 65 floors and the claim of tallest building in the city (and entire state of Missouri). Instead, that title goes to One Kansas City Place, with an only slightly less impressive 42 floors hidden behind countless square feet of black-tinted glass. Upon completion, One Kansas City Place was awarded the Economic Development of Kansas City’s Cornerstone Award for its fantastic detail, architecture and massive space – more than 1,000,000 square feet.

The building overtook Town Pavilion at 1111 Main Street as the tallest structure in Kansas City (and Missouri) at 624 feet in height, crowned by the familiar glow of colored lights, depending on the season. Most of the time, the lights shine red, white and blue, but the colors differ, for example, at St. Patrick’s day (green), in support of big hometown sports games (white and blue for the Royals, red and yellow for the Chiefs) and green and red at Christmastime.

1201 Walnut

Architect: HNTB

Though built in 1991, the skyscraper at 1201 Walnut recalls the heavy use of glass-and-granite during the downtown revitalization heyday of the 1960s and 70s. This beauty is an astounding 427 feet tall, boasting 29 floors and 13 elevators in downtown’s business/financial area. The Kansas City Power and Light Company made the move from their equally impressive headquarters on 14th Street to the office spaces within 1201 Walnut. Today, the sign on the building (the right acquired in 2010) reads Stinson Morrison Hecker, LLP, the business that currently occupies the building amongst a few smaller ones.

The Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts

Architect: Moshe Safdie, 2011

Long has the Kauffman family been present and influential in Kansas City (hint: ever hear of Kauffman Stadium? Muriel and husband Ewing founded the Kansas City Royals professional baseball team). It was Muriel McBrien Kauffman who brought forth the idea of the performing arts center in the 1990s, but passed away shortly thereafter. Her daughter Julia assumed her mother’s mission whilst establishing the Muriel McBrien Kauffman Foundation -- and in 1999, that foundation acquired 18 and-a-half acres at 16th and Broadway Boulevard for the foundation of the performing arts non-profit project. Some five years of construction, 27 thick steel tension cables and tens of thousands of square feet of glass later, the Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts is an inspiration and encouragement to the current Kansas City renewal and redevelopment movement.

The innovative design of architectural and award-winning genius, Moshe Safdie, blossomed from a mere sketch on a paper napkin while dining with Julia Kauffman, as she described her vision for the center. Safdie was an expert in his field, but the precise measurements, acoustics and knowledge required for the best quality projection in theater construction necessitated a professional. Yasuhira Toyota joined the team, a talented and widely-known acoustician.