Rails to Opportunity: A Story of Resilience in Kansas City’s Latino History

Mattie Rhodes Center, Guadalupe Center, Dos Mundos, Tropicana, La Bodega, Jose Faus, Latino Writer’s Collective, Our Lady of Guadalupe, immigration, Mexican Revolution, Westside

On a warm November day, I hop off the 47 bus at 17th and Summit in the Westside of Kansas City, Mo. just outside Los Alamos Market y Cocina. I head for the annual Dia de Los Muertos celebration at The Mattie Rhodes Center. Children with face paint dance in the street. On one end, a small stage has been erected and I head straight over, cutting through the crowd. The gallery windows fill with eerie grins of papier-mache esqueletos. I make my way past the squalling children and dancing couples toward the music and stop just off stage right next to the speakers. Here’s a perfect view of Enrique Javier Chi tossing his groomed dreads around and crooning sultry top notes over bass lines of mourning. “Cuatro anos acqui, como cuarenta en un desierto/Four years here, like forty in a desert,” he intones, plucking his guitar strings over light percussion. It’s something I understand a little too well, not being a native of Kansas City.

Photo courtesy of Forester Michael

I was born in Santa Barbara, Cali., where my father was a professor at the Brooks Institute of Photography. We only lived there for a few years before returning back to Albuquerque, N.M., where most of the family ended up after years of migration. We traded the beach for mountains and desert and I grew pudgy on Nana’s tortillas and red chile. No one thought to teach Spanish to my generation of the family. My cousins and I fought in English while my aunts shouted at us from another generation’s tongue. We built forts in the trees of my Nana’s backyard from scrap wood and fought with water and sticks. A month before turning seven, I was dragged kicking and screaming to Kansas City, where I learned what it was like to be the only differently skin-toned person in the room. It was a rough adjustment. I watched the news religiously and practiced the newscaster’s accent since the kids at church kept asking me in what country I had been born. My parents moved us to Leawood, Kans., and stopped speaking Spanish to each other altogether. I had few friends and relished in books that taught me to speak like a miniature eccentric aristocrat. I became fluent in French.

www.adolfogustavomartinez.com

Now, this feels like a different city. There’s something subconsciously comforting about surrounding myself with images I used to scour for in books. A mahogany hand laden with gold rings catches my elbow. I turn to give Adolfo Gustavo Martinez a tight hug. “What’s uuup?” he asks, squeezing my arm. He designed the logo for the 2012 celebration, dancing ghosts of skeletons wrought from bold lines. He motions his head towards the gallery and I fall in line behind him, ducking the little camps set up selling T-shirts, jewelry and art. Another giant esqueleto with a sombrero greets us at the door, bobbing low over our heads. We tiptoe and dodge through the crowd of people and pause in front of Adolfo’s paintings on the wall. “They look okay, right?” he asks me, his hand posed thoughtfully under his chin. “Muy chingon, vato,” I assured him. Altars by some of the most renowned artists in the city fill the gallery and I comb the names like a Who’s Who list: Maria Vazquez Boyd, world-renowned poet Xanath Caraza, Jenny Mendez, Robin Case, Alisha Gambino, Jessica Manco. And I’ve never seen so many marigolds in my life, all tucked carefully between offerings and depictions of the deceased. I see the signature black braid flecked with the white hair of a man named Jose Faus, an incredible muralist whose credits include the Lewis and Clark/1810 Kansas Town murals of the River Market and two near Bartle Hall, both visible from the highway. He was also my first real boss.

When I was 17, I worked at Studio 150, a program that employed students just out of high school to paint during the summer before college started. Joe and I being likeminded developed a very sarcastic relationship. At the end of the summer he told me about the Latino Writer’s Collective. He told me when the meetings were and I “yeah-yeah”’d and then promptly forgot all about it. I didn’t really consider myself a poet, then, and I certainly didn’t consider myself “Latino” enough to fit in with that group. There was no use for that label in New Mexico. I was a punk rocker and that’s where I laid my identity. I was unwelcome in the new world and uncomfortable in the old one. Something drastic had to change, so I took my professor’s suggestion and moved to Buenos Aires to learn Spanish. My grandmother was in poor health and I wanted to have a conversation with her in her first language. Immersion was the quickest way.

The last time I saw my grandmother alive, my mother and I took a side trip to Taos to visit a cousin of ours. He showed us genealogies that traced our family back to French fur trappers that had settled in St. Louis for several years before continuing down the Santa Fe trail to New Mexico, where they intermarried with the Spanish, Mexican, Native and other sides of my family. Now, my cousin Gerald and I have migrated back to Missouri, each for different reasons.

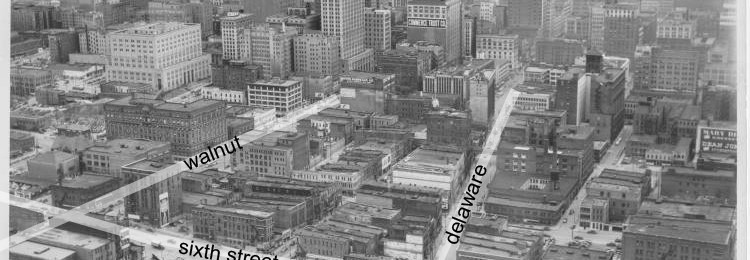

Strangely enough, most of the Mexican immigrants that settled in Kansas City would not have been here if it had not initially been for the French. The fur trappers that had made St. Louis the fur trade capital of the world decided to branch out to Kansas City, Mo. This strategic move put them in prime position to connect with the Santa Fe, California and Oregon Trails. With merchandise and pedestrians crowding the trails, the railroad was ripe for expansion. Although the Santa Fe Trail had opened up immigration from Mexico since the 1830’s, the first large wave of migration was in the late 1800’s to the turn of the century, when Mexican laborers suddenly became in high demand due to the government of the United States putting strict regulations on Chinese and Japanese immigration. Workers were crammed into boxcars in Mexico and then shipped on the rails for days until they reached Kansas City, where the survivors were put to work. Shanty towns, or campos, sprung up around the railyards with laundry lines hanging between boxcars. Those communities turned into the Armourdale, Argentine and West Bottoms neighborhoods as the immigrants grew more affluent. Some had even started to move onwards and away from the trains to the Westside neighborhood. In 1910, a new wave of immigration flooded in, many fleeing from the bloody brutality of the Mexican Revolution.

Life in Kansas City for the new migrants was far from easy. The existing residents of Kansas City were not welcoming to the new population that spoke little English and had little education. Latinos were regularly the victims of blatant discrimination that was designed to keep them segregated to their “barrios.” Landlords refused to rent to many of the immigrants, forcing them to stay in the campos in shanties or boxcars. Schools were not required to educate Latino children and turned them away from their classrooms. Shops put up signs and denied entrance to Latino customers. Mexicans were also turned away at hospitals and government agencies and denied basic services. There were very little resources available to them and as a result, the community created their own. When the first migrants arrived, there was no church that would cater as a social center for the highly religious population. In 1914, the first parish “Our Lady of Guadalupe” opened up on Twenty-Third Street and Madison Avenue, with Fr. Jose Munez. The church worked hard to spread its benefits to the community as methodically as possible.

The Amberg Group, named for Agnes Ward Amberg, who organized Italians in Chicago, opened up The Guadalupe Center in 1919 next door to the church. The constitution for the group includes a mission that “aimed to acquire a broader knowledge of Catholic Social problems and to work toward their solution.” Dorothy Gallagher, “Godmother of Guadalupe” herself, wrote down in a case study the services and organizations contributed by this group. Born to a wealthy family, Gallagher was instrumental in opening the Guadalupe Center, which provided language classes, a volunteer school, a health clinic as well as an annual fiesta that served double-duty as a fundraiser for the center. The music, food and dancing made the fiesta an integral part of the community. Gallagher’s family donated a large portion of land where a massive Spanish-style building was constructed for the Center on 1015 W. 23rd Trafficway. She worked at the Center without pay until she left in 1944, going to France to help with the reconstruction after the war.

My mother’s father’s name was Juan Bautista Salazar. He was an AT&SF railroad man and a storyteller, gathering his children around him at night to whisper about the low rumbles of the trains. Born in 1906 in the small Northern New Mexican town of Mora, he rode the rickshaw up and down the tracks, clearing brush and debris before graduating to becoming a manager. He told the seven children at his knee about a time before they were born, when he had been working with his partner over a bridge. A scheduling mishap occurred and the two men suddenly found themselves facing down a freight train. Juan Bautista’s partner, stricken with panic, jumped off the rickshaw and over the bridge while Juan clung on for dear life. My grandfather lived, his partner did not. He passed away before I was born, but I am sure that he would remember the boxcar windows filled with the faces of Mexican workers on their way to Kansas City.

In 1942, many workers were brought to Kansas City to work on the railroads and in agriculture through the Bracero Program. The United States was in need of cheap war-time labor that could easily be shipped back home when the boys returned from fighting. The program was the largest guest-worker program in the history of the United States and in light of the relations between the United States government and Mexican laborers, it is a woeful tale of exploitation. Workers under the Bracero Program were duped into signing away 10 percent of their earnings to be put into a savings plan. Once they returned to Mexico, they would ostensibly receive that money. The program ended in 1964, but once the laborers went to collect, the United States government claimed to have handed over the money to the Mexican government, who then in turn denied ever having received any of the funds. Stuck in Mexico with no money or resources for legal recourse, the workers never received reparations.

The segregation of Latinos became an issue in 1951, in what some could label as an act of God. July brought torrential rain pour that overflowed the Kaw River and the Missouri River basin, rendering the Armourdale and West Bottoms neighborhoods uninhabitable except for amphibians. As a result, entire communities of Latino families had to relocate to other neighborhoods, further populating areas in Kansas, where they faced discrimination from the school board. Realizing the absurdity of the monstrous project of building all new schools to house the new Latino students, an executive decision was made to merge the populations. In Missouri, groups like the Guadalupe Center had already started branching out into charter schools to cover where the regular public school system left the needs of the youth hanging, and there was adequate room for the influx of new students.

The line of immigration from Mexico has never completely petered out. However, the economic downturns of Latin America in the late ‘90’s – 2000’s brought a new wave of immigrants. Once again, Latin Americans were dealt a hand of harsh economic conditions and continuing violent threats from any number of corrupt organizations, including the government. Many of them joined family members and friends that were already in Kansas City and found that this was not such an inhospitable place. There are businesses now all over town that cater exclusively to the Spanish-speaking population. Immigration lawyers are not hard to find, nor is an impossibly tufted tulle quinceañera dress. Tropicana, a Michoacán paleteria, serves up churros straight out of the fryer. The long cylindrical dough is expertly coated in cinnamon and sugar and is irresistible with cajeta, a goat’s milk caramel. El Patrón on the Boulevard offers a modern twist on décor but an authentic spicy chocolate mole and a Coctel de Volverte A La Vida. At El Pollo Rey they sling whole chickens that gleam like lacquer, and lemons are sold separately. There isn’t just Mexican food to be had. For savory pupusas, El Pulgarcito on Truman Road rolls out these fluffy flat corn tortillas stuffed with meats and cheeses. Piropos north of the river patiently hand makes empanadas with Argentine flair. Bilingual and Spanish-only periodicals like “Dos Mundos” and “La Ñ Magazine” can be found in any laundromat or panaderia.

http://www.latinowriterscollective.org

Just off the corner of Valentine and Main, a small gray stone castle sits nestled, framed by a wide turret. What looks like a fairy tale is actually the Writer’s Place, a local refuse for those that combat with the pen as well as home to the Latino Writers Collective. It took me a few years and spectacularly quitting my job of two and a half years to finally attend a Latino Writers Collective meeting. I was hooked. World-renowned poet Xanath Caraza sat radiant, draped in a bright red rebozo, her book “Silabas del Viento/ Syllables of the Wind” marked in front of her. Her voice stalked the room like a shamanic jaguar, syllables rooted deeply into the ground. Chato Villalobos read his poem “Brown Eyes in Blue” and discussed what it was like to be a Latino police officer in the barrio he grew up in. Miguel Morales, reporter and accomplished blogger, has gotten the group heavily involved with mentoring children of migrant farmworkers. Having been a child laborer, Miguel understands the need for expression through creativity.

www.adolfogustavomartinez.com

Kansas City is home to an incredibly unique and self-driven Latino community. From rough canvas and scrap wood shanties have risen solid communities with strong ties in literature and art. There is now a Mexican Consulate located downtown, along with the Hispanic Chamber of Commerce and the Hispanic Economic Development Corporation. Adolfo Gustavo Martinez has paintings on display at the St. Luke’s Women’s Health Center and Arrowhead Stadium. Linda Rodriguez tirelessly works on grants and guiding younger poets while maintaining her own phenomenal writing. In Chile, Pablo Sanhueza quietly plots his return to the Kansas City Jazz scene. Of course, the Mattie Rhodes Center supplies art classes for children and adults as well as holding the unforgettable Day of the Dead/Dia de los Muertos celebration every year. The Latino voice is strong here, and it is one that will not back down. It is proof that no matter where you are from, we will welcome you home in Kansas City.