Maintaining

*Essay Contest Winner, Runner-Up

Innocence. Bryan’s and mine. Bryan easily could have been my father. He might have been me, or other way around. To be honest, there is no relation. I’m only trying to relate, to connect. But the points of contact here are less like braiding hair, more like stacking demolition bricks on a pallet. Sign reads: Heavy Lifting Ahead. Maintenance Required.

If you are retracing history for a warning sign, for a moment that could be designated turn for the worse, an act that set in motion all that followed, then here’s one possibility: Bryan Sheppard cheated on Carrie Neighbors when they were in eighth grade, May 1985. Carrie learned Bryan was hanging out with Debbie Foster over at The Cave, the neighborhood nickname for Dave Bear’s basement. Dave hollered down the stairs at Bryan, saying Carrie was in the front yard and wanted to talk. Bryan finished eating a donut, walked toward the front door, and joked to Debbie, “Watch, she’s probably gonna shoot me.” Bryan walked out the door and into the yard. Carrie pulled out her brother’s .22 and shot Bryan in the chest.

My mom always said Marlborough used to be like Mayberry. The soda fountain at Ditmer’s Drugstore. Potlucks at the Methodist church. Grandma’s large garden, Grandpa’s poker night with the neighbors. Kick the can with all the kids on the block. One of Kansas City’s earliest suburbs, a destination established before white flight really took off. Although Marlborough wasn’t annexed into Kansas City, Mo. until 1947, it enjoyed strong connections to the urban center, including a streetcar built as early as 1870, running from 85th and Prospect all the way to Westport. Good manufacturing jobs were plentiful due to the Bannister Federal Complex built nearby in 1947. Families had plenty of amenities and entertainment, including the whites-only Fairyland Park at 75th and Prospect. This is the version of Marlborough my sisters and I always heard: It was a great place to grow up. Was.

Bryan nearly died from the gunshot wound. He spent two weeks in the hospital, and Debbie stayed with him most days. Bryan fell in love with Debbie and cars around the same time. He couldn’t get a license for another year, but that didn’t stop him. He drove regardless. He never intended to drive far, just fast and faster. He liked to get Debbie in the passenger seat and go cruising up The Paseo, or fast down the long hill on old 71 highway, windows down, audible exhaust leaving a loud wake that woke the neighbors. When he crashed into a ditch, Debbie’s body collapsed into the floorboard. Bryan’s face slammed into the steering wheel.

Correction: Only parts of Marlborough developed into suburbs. The southeastern edge sloping downhill toward the Blue River and the bluffs, that part of Marlborough was more like the backwoods of Appalachia. Dead ends. Ditches where sidewalks should have been. Brush piles, tires stacked. The town dump’s stench spreading on July afternoons, steep hills, dark woods in which two narratives diverged, two paths needing upkeep, Bryan’s and mine.

Bryan and Debbie nearly died from the wreck. Once again, they spent time together in the hospital, Debbie holding Bryan’s hand, Bryan cracking jokes. By the time they finally recovered from their injuries, months had passed since either of them had gone to school. They didn’t go back. The plan was to get their GEDs somewhere down the road. Was.

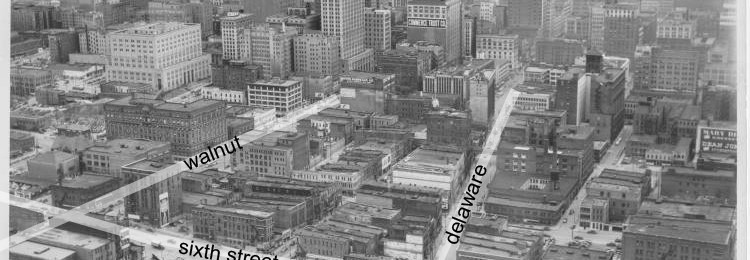

Highway 71 used to run straight through Marlborough before turning north, a two-lane route connecting downtown Kansas City to the rural farming communities further south and east. Marlborough in the ‘50s had a boom of businesses along 71: Paradise Motel, McDonald’s, Jack Stack BBQ, bars, repair shops, filling stations, and a few small factories. I imagine it back then as being like the pictures I’ve seen of the Route 66 glory days, romantic and unreal. Glory days. Was a good place to live.

After dropping out, Bryan worked on cars, found odd jobs, chased a few extracurricular girls when Debbie wasn’t looking, took drugs, drank heavily. During a bottle rocket battle with friends, one of the rockets exploded in Bryan’s face and ruined his right eye. And another day, he and a friend walked to Ward Parkway Mall where his friend smashed the window of Sears, jumped through the glass, took a bicycle, and rode away to Marlborough. Bryan walked home. The police came and arrested Bryan as an accomplice, and Bryan spent the night in jail. Not for committing the crime, but for being too close to it.

When city planners in the ‘50s mapped out the path for a new expressway, they ran it through Marlborough, right alongside the landfill near Blue River. But construction was delayed for two decades due to lawsuits alleging economic racism—the proposed route heading into the city would displace 10 percent of Kansas City’s black residents, and the highway would physically cut off the eastside from the rest of the city, all for the sake of moving cars quickly from downtown to the new suburbs. Some residents believe the highway was the final deathblow to Marlborough, like a release valve that drains a lake of half its water.

My parents wanted to leave. After my older sister and I were born in the early 1980s, we briefly lived in the house next door to Grandma. Ditmer’s had long been closed, Fairyland Park had been bulldozed, the Methodists had moved out, and so had Grandpa. We played in the same vacant lots and ditches where my mom and her siblings played as kids. By then most of our family and friends were moving to Lee’s Summit or Grandview, or across the state line into Johnson County, Kans. My dad found a vacant lot in Olathe, Kans. and built a split-level ranch on a cul-de-sac. Sidewalks. Good schools. Less crime. Less poverty. Marlborough, they thought, had changed. It had become a good place to leave behind.

Debbie loved Bryan’s parents, Jack and Vergie. When she got pregnant and her mom kicked her out, Debbie moved in with the Sheppards. She had her own room in the basement. Jack had a strict rule that Bryan and Debbie were to never sleep in the same bed while she lived there, never mind that the deed had already been done. No sleeping together. Jack and Vergie struggled with alcoholism, but both kept jobs, and Jack tried to keep Bryan away from his brothers, Bryan’s uncles, Skip and Frank, who lived nearby. Skip and Frank were junkies and drunks. Both of them were large, intimidating men who had earned the neighborhood nickname “Injun Joe” (the Sheppard family was Cherokee). They were always looking for a fight or something to steal. Bryan learned to hate them, to believe he was better than them, even as he was slowly becoming just like them.

One of my uncles. Drunk one night at a party. Left for home. Pulled onto Main Street, gunned it up the hill, faster and faster, through the stop sign, airborne over the intersecting street, crashing his car through the front wall of a house. On the other side of the wall in the living room a young girl slept on the couch. She could have been killed. But no. Only a close call. In the morning my mom heard the news and drove us back to see the wreck, the damage, see what might have been, what could be. We could easily be the drunks, the killers. Instead, I had my first beer in college. My uncle left Marlborough, became a firefighter.

Highway construction finally began in the mid-80s. Most of the businesses on old 71 shut down. A new Quick Trip opened near the new off-ramp. Cement trucks and crews drove in and out all day, and security guards worked nights to keep watch over the two trailers containing ammonium nitrate, explosives for blasting the bedrock and clearing the path.

By 1988 my parents sold the Olathe house and moved our family of six back into my Grandma’s house. I shared a room with two of my sisters. My parents began looking for a house somewhere else, anywhere else. Marlborough was only temporary.

The evening of November 29, 1988, Bryan and Debbie got into an argument. Bryan was drunk. Debbie was six months pregnant. Bryan took off in the car with his best friend, Richard Brown. They spent the night cruising the streets, stopping by friends’ houses, hanging out in the park, drinking beer, getting high. When Bryan came back home around 11:00p.m., Debbie was on the living room couch, waiting for him. The two made up and fell asleep together, cuddled on the couch. Just after 3:00a.m. Debbie woke up and hurried down to her bedroom, leaving Bryan passed out on the couch, worried that Bryan’s dad would wake and discover them breaking his rule. Bryan slept until morning. That’s his alibi.

That night I woke to the house shaking, frames falling from the walls, the breaking of glass, a flash of bright light outside like the sun shot up and then went down again in a moment. Something happened. What? My mom came in to soothe us back to sleep. But I lay awake for a while. The explosion shook everything loose, and it’s hard to piece it all back together into one fluid thing, into something that makes sense.

The news the following morning: Six firefighters killed. Someone set two fires at the highway construction site. The security guards called the fire department, and a crew of six firefighters arrived and put out the small blaze under the hood of the security guard’s pick up truck. Then all six firefighters drove their pumper trucks across the site to where another fire was consuming one of the trailers. The firefighters turned on their hoses and started approaching the trailer. It exploded. A flash of white light, then the thunderous sound. One of the guards, still standing by the burned pick up a quarter mile away, later said she lifted off the ground vertically before the blast threw her back and down on the dirt. One of the pumper trucks vanished, disintegrated, and dismembered itself down to nothing. The six firefighters died instantly, their bodies scattered around a newly-formed crater. The ambulances and additional fire crews had to wait until dawn to enter the site and search for the bodies of their friends. The fire chief, police chief, the mayor, the county prosecutor, they all said the same thing: We will find whoever set the fires. Justice will be served.

We moved two miles south. I started first grade. Nice neighborhood. Woods to explore. A baseball field. Sidewalks. A private pool for neighbors who paid their dues. Street hockey with my sisters. Bike races with friends. Scouts, church choir, youth soccer, television.

ATF agent Dave True led a federal investigation into who set the fires and killed the firefighters. He spent seven years after the explosion trying to figure out what happened that night, and whom the evidence might point to. The police briefly investigated the security guards, but for some reason backed off. For many years True strongly believed that disgruntled union workers at the construction site caused the explosions. But there was no evidence, nothing to link the union, and True’s belief did not pan out. So he simply converted. Changed beliefs. Altered what was true. Epiphany: Bryan set the fires.

In 1995, while I was struggling in middle school with algebra and acne, agent True and the ATF worked closely with the television series Unsolved Mysteries to tell the story of the explosion, and to get the public’s help in closing the case. Soon after the episode aired, promoting a $50,000 reward for information on the case, tips came pouring in. Then in early 1996, True handed over a pile of evidence to the U.S. Justice Department, the case he had concocted against Bryan and four others from Marlborough. The prosecutor charged each of them with six counts of first-degree murder, and soon they were all on trial for the crime. Among the many who testified against the accused was Carrie Neighbors, the girl who shot Bryan in the chest in eighth grade, now alleging that Bryan had confessed to her that he had gone to the construction site that night to steal tools.

Bryan and the others maintained their innocence all the way through the trial, believing the entire time there was no possible way our system of justice could take five innocent people and find them guilty. All five were sentenced to life in prison with no chance of parole.

The official narrative: Bryan set the fires. He and Richard, along with Bryan’s uncles, Frank and Skip, and Skip’s girlfriend, Darlene—all five of them went to the construction site that night to steal tools, equipment, walkie-talkies, whatever they could find. When they couldn’t find anything, they set the trailer and pick-up truck on fire as a diversion, then ran off.

There is a lot left unsaid. Is there one piece of information that would bring clarity? Would it matter that Agent True placed the $50,000 reward posters in jails throughout the state? Or that 24 of the 59 witnesses that testified against Bryan and the others were themselves convicts? Would it matter that one of the security guards had a history of fraudulent insurance claims on cars? Or that eight of the witnesses have since signed affidavits claiming Agent True pressured and threatened them into testifying? Would it matter that Carrie Neighbors signed an affidavit in 2004 admitting that Bryan had never confessed to her, and that she lied under oath only because Agent True had threatened to put her in prison and take away her child? Does it matter that Bryan had an alibi and passed a polygraph test? Or does it only matter that he had a rap sheet, brown skin, no money, no diploma, and a Marlborough address?

With an economic system that devalues places like Marlborough, and a justice system that devalues people like Bryan Sheppard, perhaps the outcome shouldn’t be a surprise. After all, progress is second cousin to closure. Both work diligently to not look back, hoping that forward motion creates no wake. The word most often repeated during Bryan’s sentencing trial in 1997: closure.

I ended up at the same middle school as the kids from Marlborough, and I became friends with a kid I’ll call Bobby Soreno. He was funny, knew a thing or two about girls, wore an anarchy t-shirt, and remembered me from when I lived nearby in Marlborough. I tried to tell Bobby about Jesus. He tried to show me how to slide a hand onto a girl’s knee on the sly. One day Mrs. Hamrick, the school secretary, pulled me aside in the hall and said, “You’re a good kid. Why are you hanging around that Soreno kid? He’s trouble. You’re better than that.”

I listened to her. I believed the official narrative, believed the dream of always escaping to somewhere else, believed my own innocence, and Bobby’s faults, and Bryan’s guilt, and all the highways between. I know now that I too can change a belief when it turns out to be false. And I know now that the truth shall set you free is a belief Bryan Sheppard still clings to while he sits in his prison cell.

Does where we come from determine where we end up? The year of the explosion I was six years old and fast asleep. Dreaming American dreams. That night when I woke, I saw my sisters, my mother. I am their alibi. I could hear from the kitchen the sound of Grandma’s police scanner turned full blast, which meant she was awake and home. I am her alibi. While I lay awake for a while after the blast, I could hear my father snoring in the next room. He was home. I am his alibi. All present. Accounted for. Safe. Home.

On a chilly December day last year, I went to visit Vergie, Bryan’s mother. There’s a No Trespassing sign in the window, and another that says No Smoking, Oxygen in Use. Vergie welcomes me in, lights up her first cigarette of the day, mutes the TV, and takes a swig from a can of Busch Lite. It’s two in the afternoon. I ain’t been a wonderful mother, she says. I’m just a mom. But I remember everything. She tells me everything. All of this and more. I try to listen. He was no angel, and I ain’t been a wonderful mother. I remember all that he’s been through, all he’s pulled, piddly-ass shit and all. But that’s my baby in there. And I want him back.

After leaving Vergie’s I drive by my grandma’s old house. Another one of my uncle lives there now, the only one of us who never left. The house paint is faded, the grass overgrown. The water and electricity have been shut off. Immovable cars fill the driveway except for the front edge near the street where my uncle crouches to fix his motorcycle. I pull over and get out to say hello. Tell him what I’m up to. Tell him what the hell I’m doing in the neighborhood. I ask what he thinks of it all. Oh yeah, he says, they definitely got the right guys, Frank and Skip and Bryan and them? Nothing but trouble. And anyway we all needed closure.

917 W. 43rd St.

Kansas City, MO 64111-3133