Lost in Plain Sight – Kansas City’s West Terrace Park

“Nature has done all it can to make the place attractive and we by our negative attention have done all we can to make it unsightly.”

-John W. Speas, speaking of the proposed West Terrace Park site, November 1893

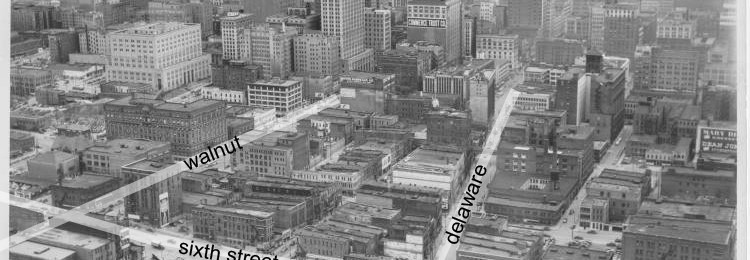

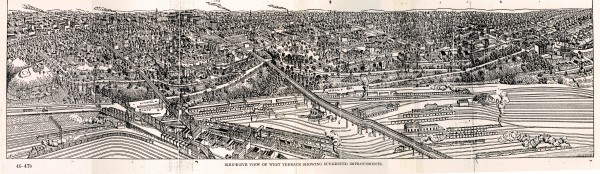

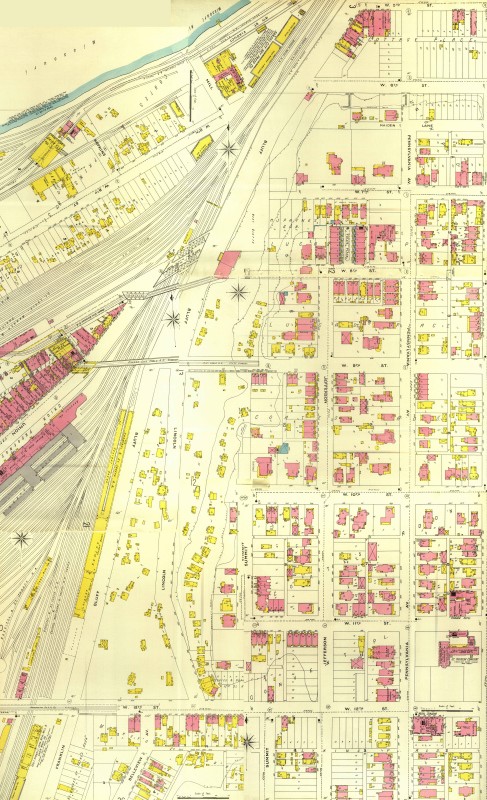

Thanks to the livestock trade that had taken root in the West Bottoms, Kansas City’s economy was booming by the late-1870s. Union Depot, the city’s first large-scale train station was constructed at the base of the West Bluffs, the rock ledges that elevate downtown above the floodplain of the West Bottoms and the Missouri River to the north, and began bringing passengers in and out of the city in 1878.

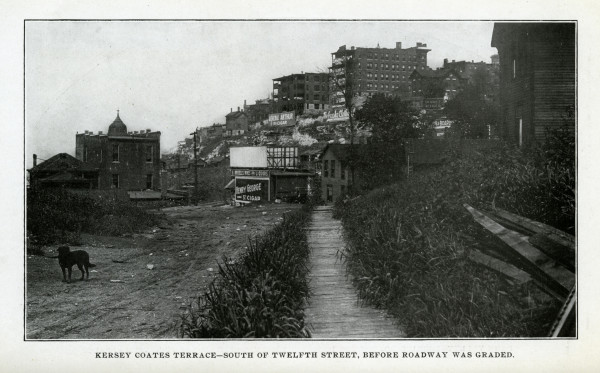

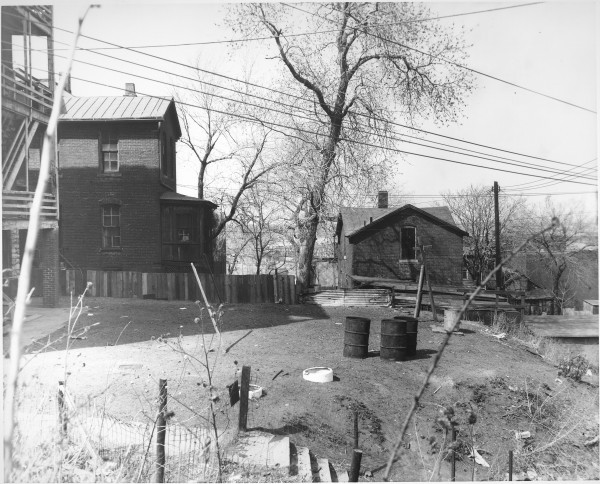

Upon stepping foot outside, travelers with more refined sensibilities would have faced the visual affront of a steep, rocky incline spotted with roughhewn houses that were, as one reporter writing for the Kansas City Star in 1896 described, “wonderfully and mysteriously made, of odds and ends of dry goods boxes and other refuse lumber.” Further subtracting from the aesthetic potential of the bluff wall, another Star reporter surmised a gaggle of “ugly billboards that for years have made the West Bluffs still more unsightly.”

By the middle of the 1890s Kansas City was playing catchup with the growing City Beautiful Movement that had come to define architectural and landscape design for cities on the national scale earlier that decade. Proponents of this planning school of thought sought to remedy the crowding and associated ill effects of urban tenements by uplifting their citizenry through monumental buildings and inspired landscape architecture.

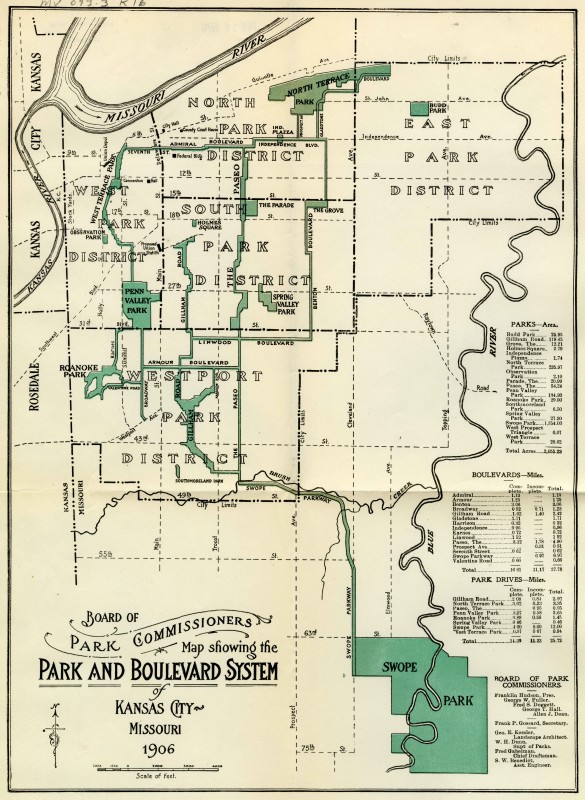

In Kansas City, August Meyer, the Park Board’s first president, tasked landscape architect George Kessler in 1895 to design an elaborate park and boulevard system that would both beautify the city as well as uplift its citizenry.

Included within this system was a series of intricate park and landscaping features that would completely erase what many viewed as the stain of the past from Kansas City’s West Bluffs and erect in its place a stately park worthy of the affluent Quality Hill neighborhood sitting just to the east as wells as a metropolitan city on the rise.

However, it is one thing to lay down plans on paper and quite another to bring them into fruition. Ultimately it would require years of legal squabbles that would divide early Kansas City opinion makers to bring into reality Kessler’s vision, West Terrace Park – a name that has now been nearly lost to many Kansas Citians.

Fast forward 120 years later and the buzzing of chainsaws and shouts to stand clear shatter the serenity of a Saturday morning in Quality Hill as overgrown tree limbs fall and crash to the ground. Workers from the Kansas City Parks and Recreation Department busy themselves clearing the overgrowth from the stone retaining wall that defines the northwest extent of this historic district. Both Ermine Case Jr. Park, located to the north of the site, and an office building immediately to the south, are quiet on this spring morning. This work has come at an opportune time as the future Apex at Quality Hill apartment site, located directly adjacent to this morning’s activity is also quiet. Once completed, the Apex will add 138 market-rate living units whose rent will range from $1,100 to $1,900 per month and if the plans of developers are fulfilled, will attract affluent young professionals to the neighborhood. An observer strolling by might easily assume that the cleanup effort is related to this project. The truth, however, is that the work has resulted from a grassroots effort to restore what is left of one of the city’s first showpiece parks.

Many may assume that the stone towers and massive retaining wall located above Interstate 35 to be a decorative extension of Case Park, but according to the Parks Department, these features are actually the physical remnants of the long forgotten West Terrace Park, an area roughly following the bluff wall from about 6th Street south to 17th Street and from Interstate 35 west to the residential and business areas of Quality Hill. There was a time that these structures, along with a limestone grotto located at the base of the stairs, were centerpieces for Kessler’s statement park meant to serve as a showpiece for the city. While the area is officially acknowledged by the Parks Department, its integrity is described as compromised and has been only marginally maintained for as long as anyone can remember – that is, until very recently.

Below the watchful eyes of the stone towers a group of volunteers is hard at work using their own tools and supplies in a cleanup effort. Among the group is Sean Owens, an architectural designer and organizer of the group Take back West Terrace Park. Owens recalls spotting the semi-hidden stone structures while taking photos in the West Bottoms during winter of 2014, and remembering the first time he noticed the towers from the backseat of his parents’ car as a child. Somewhat concerned about what the remnants of the park might conceal, he convinced an associate to accompany him on a scouting missing. They were shocked by what they found “…the old lower stairs!” Owens said. “They were totally buried in mud and had trees and honeysuckle growing out of them, but they were still there. I knew I wanted to take action. I didn’t want to just be an observer.”

With that feeling, Owens approached the Parks Department and met with officials at the site in February of 2015. “We walked around and I pointed out the things I wanted to do,” Owens said, “and tried to make them see my vision. They allowed me to organize these events and get the stairs uncovered.” He states that the level of support from the Parks Department has been great and points out that their forestry staff participates in each of the organized cleanup efforts helping to remove dead tree limbs and cut through the dense vegetation. Owens’ plans for the park may seem grandiose considering its current state of decay. “If I could do anything, then I would bury this part of the highway loop, or remove it all together. I can imagine a deck over the highway around the stair area. A sculptural, twisting stair tower that makes its way down to the West Bottoms would be amazing.” He continues, “I also have more immediate and perhaps more realistic ideas. There should be a large rock barrier between the highway and the park. Then the stairs could be completed. Next, the city could build a sidewalk to connect the path to the 12th Street Bridge. It would be a great place for joggers and people simply looking for a scenic walk through an interesting part of our great city.”

Yet, before any grand visions can be made concrete, this group of volunteers has the rather weighty task of digging out the stairs from beneath nearly fifty years of soil erosion intermixed with glass shards from the innumerable bottles that have been carelessly tossed over the stone wall through the years, a process made all the more taxing thanks to the region’s rain-soaked spring. Graffiti and extensive litter cleanup will have to wait for another day. Progress from the group’s previous efforts is visible as a team of diggers work to extend a deep channel from top to bottom that will at least make the stairs passable and provide a foundation for future work. I arrived today with shovel in hand and immediately got busy. It is here, I believe, perhaps even more than municipal support, where Take back West Terrace Park demonstrates its greatest need – community and grassroots support. Ultimately, for the project to be successful, the people of Kansas City will need to communicate that the future of the park is of importance to them. While the prospect of new housing developments directly adjacent to the park will surely pressure some form of action, it remains to be seen what form that will take. After all, the lure to simply kill off such a degraded site must be attractive, a course that certainly offers the least resistance and would be easiest on already stressed city coffers. Try telling that though to the team of volunteers hard at work attempting to bring the park back from the brink.

The threat of demise is nothing new to West Terrace Park. Organized opposition to the very idea of the park began almost immediately following announcement of the Park Board’s initial plans. One camp of opponents based their arguments upon the long-term usefulness of the park site. Many simply did not see the point of spending tax dollars on a park designed, in their estimation, only to provide travelers with a scenic view while providing no benefit to the city’s actual inhabitants. By 1899, with construction on the park yet to begin, a then recently appointed member of the Parks Board, Joseph V. C. Karnes, openly spoke out against West Terrace Park, stating in simple terms “It will be a failure.” He continues his attack with an assessment of the site’s natural characteristics:

You can’t grow things on that ledge of rock with the hot western sun beating upon it…the rains cause part of it to slide and new ledges or rock crop out. Very heavy retaining walls will be required to hold the large amount of earth it will take to cover the ledge sufficiently…These will be expensive and after all these immense sums have been spent in buying the land and building walls and surfacing the rock, of what use will it be? There will be no place where the people can congregate…First let us have what is absolutely needed for the comfort and enjoyment of the people and then turn to ornamentation.

Interestingly, stating what many already knew about the flood-prone site of Union Depot, Karnes also makes the case that beautification of the site would be pointless considering that plans for a new train depot located to the south were already in the works. True to Karnes’ words, Union Station would divert rail passengers away from their unsightly stop in the West Bottoms by 1914.

Another group of park opponents rallied against compensation to be paid by the city to West Bluffs property owners. This camp claimed that the compensation package awarded by the city in 1896 was insufficient to cover the loss of city-condemned property. The Taxpayers’ League was formed to provide a united front for a fight that would ultimately be decided in the courts. The case eventually found its way to the Missouri Supreme Court with a lower court’s decision in favor of the park being upheld in 1903. The park knockers, as opponents of Kessler’s parks plan were dubbed, were represented by such notable figures as: Jemuel C. Gates, Missouri Supreme Court judge Francis M. Black, head of the National Bank of Commerce William Stone Woods, Thomas H. Swope, Father Bernard Corrigan, amongst many others, all attaching their names to petitions asking the Parks Board to repeal the West Terrace Park ordinance. Rather than squabbling over fees paid to property owners, however, the primary point of objection expressed through their petition being that “the bluffs are worth nothing and should therefore not be paid for.” Their point echoing that made by lawyers working on the initial compensation package who advised the city not to pay residents of the West Bluffs who they deemed to be “squatters and entitled to nothing.” Fortunately for residents of the West Bluffs, in 1896 Judge Edward L. Scarritt instructed the condemnation jury to include fees not only for land owners, but also for West Bluffs residents when calculating the final compensation package.

The land owners in this story can easily be accounted for, the two largest holdings belonging to Charles G. Hopkins and to the estate of Kersey Coates, who, amongst a long list of West Bluff and Quality Hill property owners received their settlement payments from the city in May of 1900. The latter group, on the other hand, those who made their homes amongst the unsightly billboards and rocky soil of the West Bluffs, found their prerogatives factored out of early city planning. This group was largely African-American, many having resided along the edge of the West Bottoms since the end of the Civil War. What is clear is that they apparently were not entirely without recourse. A reporter for the Star wrote:

There is great excitement among them when they heard that their homes were to be taken and they were to receive nothing in return. The negroes swarmed in delegations to the courtroom, where the condemnation proceedings were in progress, and lawyers took charge of the combined cases of seventy of them with the result that they will be paid for their homes when forced to move out.

![[7] West Bluffs House and Family - ca. 1900 JPEG – Image of family and residence captured by Parks Department authorities prior to the clearing of the West Bluffs in 1904. Missouri Valley Special Collections, Kansas City Public Library, ca. 1900.](http://www.squeezeboxcity.com/sbc-content/uploads/2015/08/West-Bluffs-House-and-Family-ca.-1900-JPEG-copy-600x370.jpg)

Interestingly, this account was published in 1896 – four years before settlements were finally awarded and a full seven years before the city finally began clearing the West Bluffs in preparation for park construction. The story of West Terrace Park begs several questions regarding these individuals. How many West Bluffs residents actually received their compensation packages? Did they relocate early in the planning stages for the park, or did they merely return to their day-to-day lives during the long years when it was unclear if the park would even be built? Lastly, how many new residents chose to build homes along the bluff regardless of the condemnation proceedings only to miss out on any form of compensation? Satisfactory responses to these questions are difficult to uncover. What is clear, however, is that many were taken by surprise in August of 1904 when the Star ran the headline “Shacks Are Being Razed.” It was written that:

…more than one family this morning had to set their furniture in the road while the park laborers climbed upon the roofs and began ripping off the shingles, weather strips and tar paper. At noon children were seen still guarding the household effects piled up on the ground while their parents were hunting new places of abode.

The author continues by describing just what these families would have observed that day:

…the workmen seemed fairly to swarm over the hillside. There appeared to be men for every building and they made short work of the West Bluffs architecture. There would be a few rips at the roofs, the sides would be pulled out whole…

With the dual pressures of land clearance for the park and expansion of the booming stockyards industry, many displaced residents would have relocated to areas east and south of downtown, the bulk of the area’s African-American residents putting down roots on the city’s eastside.

West Terrace Park was the last of the three major parks initially approved in Kessler’s 1893 plan, opening after both the North Terrace and Penn Valley Parks. Construction was a lengthy process, the park actually being added to and modified in stages from the early 1900s through the 1940s. The earliest efforts focused upon the driveway and retaining walls, with West Cliff Drive, later renamed Kersey Coates Drive, a scenic thoroughfare tracing the base of the West Bluffs, and the walls and towers near 10th Street being completed by 1906. The stairs leading down the bluffs to the lower landing and grotto were added in 1908. The site was a popular destination for Quality Hill and Westside neighborhood residents for several years thereafter.

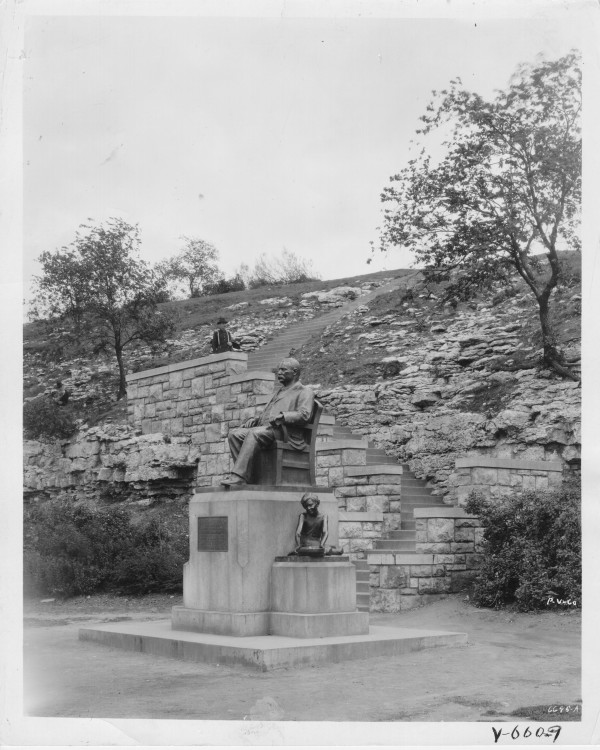

Controversy returned in 1913 when Mulkey Square, an area then within West Terrace Park, was selected as the site for a memorial statue of James Pendergast, a West Bottoms saloonkeeper, city alderman and founder of Kansas City’s notorious political machine. Protesters took issue with the Parks Board for honoring a figure so closely associated with the liquor trade and what many viewed as rampant political corruption.

Yet, the dissenting voices were temporarily silenced as the statue was officially dedicated on Independence Day of that year in a ceremony presided over by James’ younger brother and political heir, Tom. The statue, now unknown to many, has occasionally been vandalized over the years and was eventually relocated to a more visible position within Case Park. The park’s final major improvement occurred in 1941 at the behest of Henry McElroy, notorious Pendergast Machine figure and city manager, Works Progress Administration labor being used to construct a magnificent observation point at the park’s northernmost extent with a view of the West Bottoms and the city’s new Municipal Airport.

As with many downtown neighborhoods, Quality Hill had become synonymous with urban blight by the 1950s. Along with many other American cities, Kansas City began accepting federal funds to finance urban renewal and expressway construction projects during this era. West Terrace Park had survived a handful of legal assaults in order to come into creation, but would all but be destroyed by our efforts to eliminate blight in postwar Kansas City.

The integrity of the site specifically intended to add beauty to the city’s West Bluffs was compromised in order to make way for I-35 in 1966. Kersey Coates Drive as well as the stone grotto at the base of the stairs were lost entirely. The condemnation action necessary to make way for the expressway effectively carved the park into the subunits that exist around it today: Jarboe Park, Mulkey Square and the larger Case Park.

Today Owens has setup a volunteer check-in station with release forms from the Parks Department under the cover of the towers. As I continued to dig, all the while hoping to unearth a forgotten relic of Kansas City’s history (no luck), my mind puzzled over whether or not the park is really worth saving at this point. I considered John Speas’ words spoken in 1893 in regards to the undecorated West Bluffs “…we by our negative attention have done all we can to make it unsightly.” Is it possible that the sum total of our negative attention paid to West Terrace Park over the years outweighs anyone’s good intentions, however noble and inspired they may be? It is easy to be seduced by the park’s allure when viewing images of the site in its prime, but such feelings will do little to insulate visitors from the harsh realities of a park directly abutting an urban interstate highway. Going forward, Kansas Citians will have to decide what is to become of their long lost park.

An early morning rain shower mixed with afternoon sunshine has brought humidity levels to oppressive levels and I find myself covered in mud and near the point of physical exhaustion. Curiously Owens seems unfazed. “I love Kansas City, history, architecture, and the outdoors. West Terrace Park brings all that together.”

Those interested in helping out are encouraged to follow Take back West Terrace Park’s Facebook page for updates and scheduled cleanups.