J.C. Nichols

Country Club Plaza, Spanish architecture, Federal Housing Administration, redlining

“Never did so great a community owe so much to one man.”

-Reverend Warren Grafton

Jesse Clyde Nichols, the man behind the Country Club Plaza. It’s his most acknowledged achievement, but dear me, he was so much more than the creator – visionary, mentally and physically – of one of the largest and prosperous commercial areas in the whole United States! Not that this wasn’t already quite an impressive addition to his resume. This man was involved in his community. He cared about Kansas Citians. And he was one smart cookie.

He did study at the University of Kansas, mind you. He studied economics; hell, he ate, slept and breathed it.

His brilliance, amity and devotion earned him several board seats after the success of the Country Club Plaza. The Kansas City Public School board, numerous project boards, and with Liberty Loan and the Red Cross – you name it, he served on or with it. So renowned for his work, J.C. Nichols helped create and lobbied for President Roosevelt’s Federal Housing Administration… at the President’s personal request.

Where did this guy come from, right?

A farm in Olathe, Kans. He worked on the farm and held a store job as early as eight years old. He was well known for his money-making schemes as a kiddo, while valuing the hard work it took to get it. He never went without a job, whether formal or farm-related (he’d herd cows to and fro’ the pasture for farmers, earning fifty cents a month). Even during college, J.C. worked odd summer jobs.

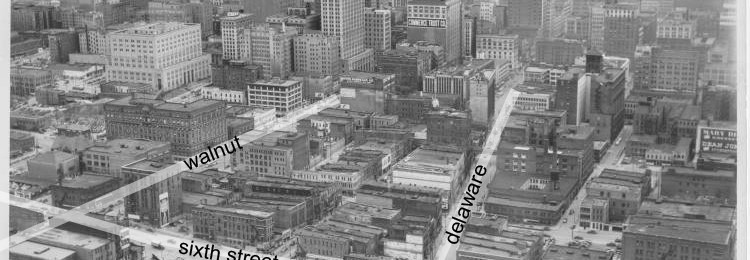

His sales skills were apparent early – he created his high school debate team. The school didn’t have one, and damn it, Nichols wanted one. Thusly, he made it happen. Years later, Nichols co-purchased a block of land, high above the floodplains of the city. People were eager to escape to higher ground after the flood of 1903. And Nichols’ brilliant move in advertising it as “The Highlands” earned him enough money to purchase more land (solo this time) on Grand Blvd. This would become his legacy, the first commercial development equipped for automobiles, the one and only Country Club Plaza.

Nichols did much for the community, but like any story, his is incomplete without addressing the harsher truths. He pioneered the installment of Homeowners Associations throughout the city – and the country, as well – during the early and mid-1900s. A mix of race and class lessened home values, you see, as racism was alive and well and widely accepted. It was even legal; these particular laws enabled Nichols and his H.A.s to forbid black people moving into the neighborhoods he developed. The associations were prevalent in desirable neighborhoods, and Nichols heavily influenced the continued segregation, racial boundaries and urban decay in Kansas City. The remains of said influence are nearly as pervasive as ever… if only slightly more veiled.