Gully Town

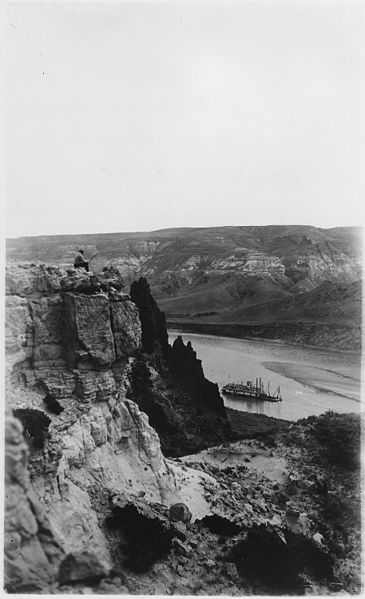

In the Town of Kansas (turned Kansas City, Mo . in 1853), bluffs of limestone once towered over the landscape, untouched and formed of their own free will. French fur trappers and Kansa Indians traded in the wild area below the bluffs, known later as the French Bottoms when the trappers settled there. In came the railroad and cattle industries to the city, and this boomin’ cow-town, boozin’ and a-bustlin’ neighborhood adopted a new name: the West Bottoms.

But for its first 30 long years, the bluff-land was dubbed with another, significantly less flattering name: Gully Town.

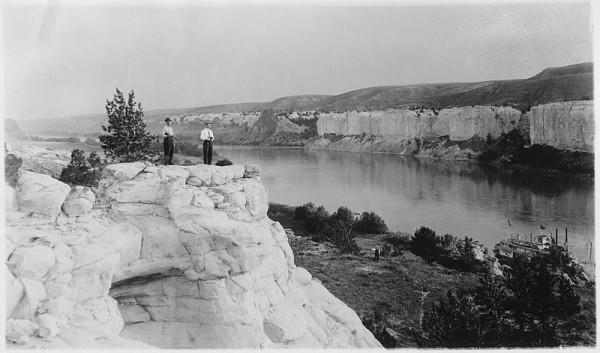

If you’re unfamiliar, a gully is a sort of trench or ditch created by erosion. The natural gullies in Kansas City have formed over time, the river and ravines throughout the bluffs etching into the earth. The prominent difference between a trench or ditch and a gully? The constant flow of water could eat into stone or soil in some places more than 10 or 15 feet deep. To put it bluntly, gullies are potentially quite dangerous.

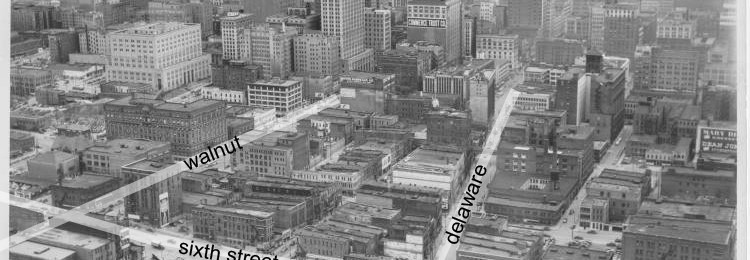

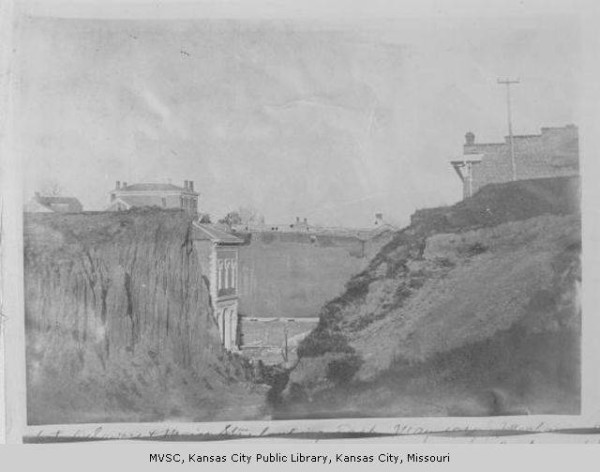

And here, you must think that these natural gullies must be how Kansas City earned a name like Gully Town in the beginning. But no, it actually wasn’t for the many trenches created by nature — it was those Gully Towners, cutting and digging into the limestone, making streets and foundation for homes into the rock and soil itself. These man-made “gullies” grew and rose and ascended the bluffs rapidly.

Kansas City was a small town before the coming of the railroads and the stockyards in the 1870s, with a population just upwards of 4,000 people. And its reputation in those early to those years wasn’t exactly amicable ’round the United States. It was common in Gully Town to keep a gun beneath one’s pillow, and weapons were worn openly during daylight. Horace Greeley, editor of the New York Tribune, went so far as to call Gully Town a “malignant stronghold of persecution and violence.” Out-of-staters thought the gully-diggers ridiculous for settling the bluffs, how strange it was to build upward like that!

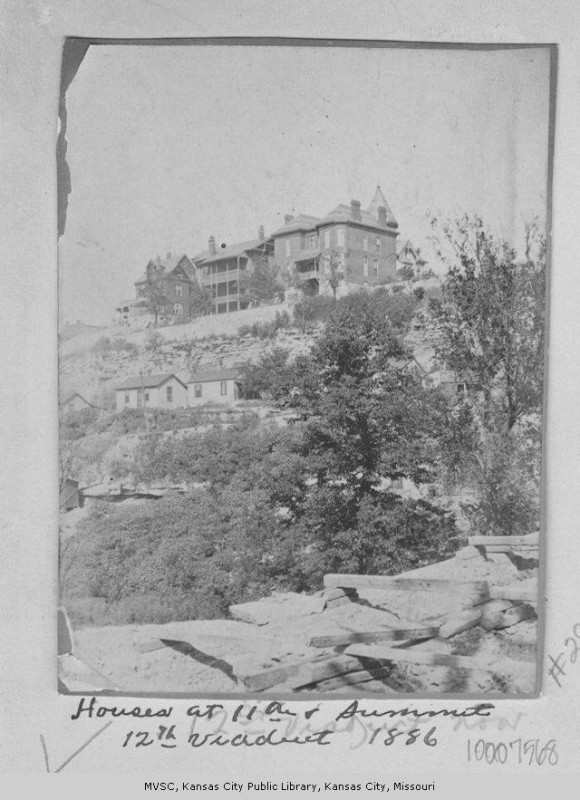

The Gully Town population over on the bluffs consisted largely of freed slaves come northward and poor immigrants from Italy, Germany and Ireland. These honest working folk eventually fled Gully Town for less-dangerous, cleaner conditions elsewhere in the city. The area and living conditions only worsened as slums, prostitution and countless saloons earned the West Bottoms the “Wettest Block in the World” title, and the transiency due to the busy Union Depot railroad invited theft and ne’er do wells.

Twas the building of the Hannibal Bridge in 1869 that brought an end to much of Kansas City’s less-than-desirable reputation. The bridge, the first to ever span the Missouri River, literally transformed the little Town of Kansas into a crossroads of trade and livestock exchange, and one of the country’s busiest rail hubs. The Gully Town name didn’t stick after the city’s swift development and success – not to mention, once the lovely and wealthy Quality Hill neighborhood was established atop the bluffs by Kersey Coates (the man who’d had the single most Kansas City influence in the funding of the Hannibal Bridge). Quality Hill and the rest of the city to come no longer merited a name such as Gully Town.