From Jitneys to Lyft: Kansas City’s Transportation Hang-Ups

Public transportation, private transportation, Uber, Lyft, Yellow Cab, KCTCA

A mass of downtown workers huddled together at the corner of 8th Street and Grand Boulevard, coat collars upturned against the January chill, attention focused to the north in search of a streetcar that would eventually arrive to take them home. The evening sun had all but faded, taking what little warmth it offered as a few in the group grumbled that the drivers on this line always seemed to run late. Others chatted, voicing their fear that the car would be full to capacity by the time it reached them. Most hoped that one of the straps dangling from the roof would be free, or simply for space enough to stand with a little breathing room. All just wanted to get home. Suddenly, a hulking Model T bus came to a rickety stop about half a block to the south. Several began to break away from the crowd one by one, each digging deep into pockets and purses for coins and calling out to the vehicle’s driver. The first to arrive coin in hand were permitted to climb aboard, those who lagged behind were left to wait in the cold as the motor bus merged back into rush-hour traffic. In the early 1900s, most would have recognized this scene as the latest transportation fad to hit Kansas City: the jitney. Jitneys became the talk of the town. Many Kansas Citians may have even wondered if perhaps it was time they tried it for themselves.

On the evening of January 18, 1915, the Kansas City Star reported that the city’s first jitney bus had started operating in the city. Jitneys were privately owned early automobiles whose owners accepted set fares to transport people along an established route. The name was taken from a slang term for a nickel, the usual fare charged by the drivers for a ride. Noting a very similar visual identification tool to that used by Lyft drivers of today, a writer for the Kansas City Star described the first of many jitneys to come:

A five-passenger Ford motor car bearing a big “5” on the radiator, indicating the fare, was the beginning this morning of Kansas City’s innovation in transportation, the “jitney,” one W. H. Miller, owner and driver of the car, smiled and collected the nickels as he ran back and forth over his route between Twelfth Street and Benton Boulevard, and Eleventh Street and Grand Avenue, at the rate of three round trips an hour.

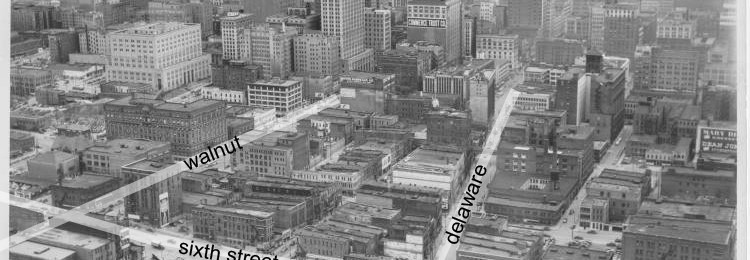

Miller’s route was in no way a matter of happenstance. Rather, he was simply trolling where willing passengers could easily be found – that is to say, along an established and popular streetcar line. In 1915 the 12th Street line traveled from Jackson Avenue in the east, through downtown, and eventually wound up in the West Bottoms before making a return trip. Miller, by circling 12th Street between Benton Boulevard and Grand Avenue, had simply claimed the line’s middle portion for his own.

A “jitney invasion” swept over Kansas City early that year. Many residents were so enamored with the new transit option that jitneys began to be viewed as the reasonable replacement for Kansas City’s crowded streetcar lines. Many Kansas Citians responded to the excitement by becoming jitney operators themselves. A young woman described her circumstances to the editors of the Kansas City Star and asked to be advised as to whether or not it would be profitable to operate a jitney bus of her own:

I am a young woman living near Armour Boulevard and Main Street and I work in a manufacturing plant near Sheffield. It’s a long, tedious trip to work and back by streetcar. If I purchased an inexpensive 5-passenger motor car could I make it pay its own running expenses in taking me back and forth to work by this process? I would be going and coming in the rush hours and I believe I could pick up eighty cents a day in this manner, at the same time solving my transportation problem.

The paper responded the next day by publishing an account of one female driver that had already found no shortage of patronage since beginning her business venture:

…they pile into the seats as soon as I get to the station and they would climb up on top, sit on the hood and perch on the running boards if I would let them…I wanted to help my husband and I think I have a perfect right to do it. We are young and if I can help and we can get a start early in life I think it’s the thing to do. I have driven a car for four years, and if I do say it myself, I am considered a good driver.

The new fad was so pervasive that a national convention of jitney drivers was held in Kansas City in May of 1915. The fledgling automobile industry pounced upon the opportunity to boost sales and sent representatives to promote everything from tires to headlamps. Despite all the gaiety and sense of economic empowerment caused by the jitney boom, convention organizers made sure to set aside time to discuss the wave of backlash from municipal and transit authorities that was sure to come.

Indeed, not all Kansas Citians welcomed the new mode of transportation. Many public and transit officials must have felt threatened when criticism of Kansas City’s vast streetcar network in the local media ramped up almost immediately following the explosion of the jitney craze. Newspaper writers responded to the excitement generated by the jitneys by characterizing Kansas City’s network of streetcars as inefficient, overcrowded, and quite simply, not with the times. One fed up citizen wrote:

When people used to lick about the poor service the Metropolitan was giving I used to uphold the Metropolitan…but I must admit that I was surely given a surprise Friday when I passed Twelfth and Grand expecting to catch a [streetcar] home, I saw hundreds of people standing in front of 1133 Grand. It seemed as though there was no let up to the crowd gathering to ride the jitneys. When a car for Fifteenth and Indiana showed up I got in to try my first ride…I must admit it was a novelty and a pleasure. I had healthy pure air instead of the foul air in a close streetcar. I will take them every time and encourage the men and women who are trying to make an honest living.

Any alderman who attempts to bring up something in the council with the intention of making the Jitneys quit business will surely put himself in disfavor with the thousands of friends of the new service.

Municipalities and transit interests across the country recognized the very real threat presented to streetcar companies and began slandering jitney drivers in a fashion that would be mirrored by critics of ride-share services today. Like their 21st century counterparts, jitney drivers were decried as being unlicensed, unregulated, and an overall threat to public safety. Nevertheless, demand for jitney buses continued to soar beyond 1915, peaking in November of 1919 with over 450 drivers transporting an estimated 40,000 to 50,000 Kansas Citians daily, a significant number or citizens whose fares were no longer paying for rides on the city’s many streetcar lines.

One newspaper author summarized the public’s frustration early in 1915:

There is no city wherein the citizenship wants to reduce the earnings of the [streetcar] companies to nothing. There is no desire to force them into bankruptcy. There is, however, a desire on the part of the citizenship for good and for adequate service – a seat for a nickel and not a nickel for the privilege of straphanging. The long continued rule of action by [streetcar] companies in all cities, with long term irrevocable franchises, contempt for the public comfort and sneers at the public demands…

…Of the three elements involved – the [streetcar] companies, the jitney bus and the citizenship – is consideration to be paid to [streetcar] companies only? Is straphanging to continue simply because the [streetcar] companies make money by it? Is the jitney bus to be put out of business because it competes with the [streetcar] companies?

Streetcar interests and legislatures in the city acted in September of 1919 with what must have seemed to the public like a resounding yes to all three of these questions. First, in an effort to stave off financial ruin, streetcar fares were raised from six to eight cents. When you consider that the jitney drivers were already charging less for a ride prior to the rate hike, then it is easy to understand why a nickel trip in an uncrowded car seemed so attractive to so many. In turn, it did not take members of the Kansas City Council long to launch their assault on the jitneys. Just days following the rate hike, an ordinance to regulate the jitneys was passed and eventually signed into law by Mayor James Cowgill.

The new law established fixed jitney routes set safely away from streetcar lines, limited the number of drivers that could operate upon a route at any one time, developed a city licensing system for drivers, and provided a salary for a jitney inspector charged with insuring that jitney buses met a strict set of safety standards. The death nail for the jitneys, however, proved to be a provision of the law requiring each driver to contribute $2,500 to a bond fund established to settle accident claims made by jitney riders involved in motor accidents. On the morning of September 4, 1919, the Kansas City Times reported passage of the new law with the simple headline “The Monopoly Wins.” And win they did. While some of the jitney drivers attempted to continue on in accordance with the city’s strict regulations, the fact was that the jitneys had quite simply been legislated out of business and Kansas Citians returned to the streetcars.

Despite the fare hike, the Metropolitan Street Railway Company entered financial receivership in 1920. Of course, the entirety of the blame for the decline in streetcar usage amongst Kansas Citians at that time cannot be placed solely at the feet of the jitney drivers and their passengers. To be sure, allegations that operators of the Metropolitan sought to squeeze every cent possible out of a populace with few transportation options while constantly degrading its level of surface predated the jitney boom. The longstanding nature of the problems affecting the Metropolitan is evidenced by the gargantuan size of its estimated 5.5 million dollar amassed debt at the time of its entrance into receivership proceedings.

While the profitability of operating a private jitney was nearly wiped away as a result of the city’s 1919 ordinance, the arrival of reasonably priced cars on the market made the prospect of owning and commuting by individually owned automobile a viable option for many by the early 1920s. Another challenge to the streetcars arrived in 1924 when the Kansas Cities Motor Coach Company began carrying passengers between downtown Kansas City, Kan., and Union Station on the Missouri side of the state line via motor bus. The streetcar interests fought the new buses with the very ordinance they had used to shut down the jitney drivers – and once again prevailed. The Motor Coach Company ceased operations later that same year. By this time, however, the streetcar interests had become convinced that motorized vehicles were indeed the wave of the future and on New Year’s Day in 1925 Kansas City Railways began operating six of its own buses, thereby mapping out the future of public transportation in the area.

As the prospect of automobile ownership soared during the country’s post-war economy, streetcar ridership in the city plummeted. The Kansas City Public Service Company continued to operate its lines until 1957 when its many miles of tracks were ripped up and paved over during a slew of federally backed urban renewal projects. Today, aside from the occasional bit of track protruding from the asphalt or tales of the old 8th Street Tunnel, little evidence of the city’s once vast streetcar network remains.

Fast-forward nearly a century later and it is clear that Kansas City continues to be hung-up on the issue of transportation. When the KC Streetcar project was approved by voters in 2012 to transform Main Street as we know it today, city leaders were already scrambling to secure extensions to the 2 mile starter line before construction had even begun. Critics of the project cite the high cost of streetcar projects in similar cities, an unproven association with increased development, poor planning, and an undue tax burden placed at the feet of downtown property owners, many of which do not reside in the special streetcar taxing district and therefore were not permitted to vote on the ballot measure that made the project a reality. Further, they add that the public’s transportation needs have already been met by the Kansas City Area Transportation Authority’s extensive network of bus lines. Supporters of the project, on the other hand, do not agree with their bleak assessment and maintain that buses simply lack the urban mystique likely to attract millennials to live and work downtown.

Additionally, the ride-share company Lyft began its Kansas City operations in the spring of 2014. For those unfamiliar with its services, Lyft connects vehicle owners with passengers in need of a ride. Drivers are summoned using the company’s smartphone app, where users can read vehicle descriptions and reviews of drivers and passengers alike before making any commitments. Rather than charging a traditional metered or set fare, as with a taxi or other livery car services, Lyft sets a “suggested donation” payable to the driver. Drivers must have the vehicles inspected by a Lyft representative, pass a background screening, be appropriately insured, and echoing back to the large 5 promently displayed by many jitney drivers, display a large pink fur mustache upon the grill of their vehicles before accepting riders. In addition to added income, Lyft drivers describe a feeling of empowerment gained through meeting new people and through their participation in the so-called peer-to-peer economy, another similarity to their early 20th century counterparts.

Lyft appeared to be off and running and the buzz generated by the pink mustachioed cars zipping around town showed little sign of slowing. Yet, mirroring the response to the jitney craze, many public and business officials have called for Lyft to apply the brakes. Representatives from the Kansas City Transportation Group – operators of Yellow Cab, Who’s Driving You? – a national organization whose aim is to raise awareness of safety concerns associated with ride-share services, and the City Council were all quick to condemn Lyft’s business model. Each has asserted that the service represents a public threat due to the fact that it enables its drivers to sidestep the public regulation, oversight, and operating fees other Kansas City-based taxi and livery companies must navigate in order to legally operate. Mayor Sly James himself, often noted for his staunch support of innovation and fresh business models, has spoken out against Lyft for its operating practices. In a blog posted to the city’s website, Mayor James called Lyft to task for not contacting city officials until the very day its drivers began picking up riders and for failing to comply with established taxi and livery service ordinances.

Actions quickly followed. In early May the City Council acted to close a legal loophole that allowed Lyft drivers to operate in the city with impunity and filed a motion in a U.S. District Court to halt its operation. At the same time police officers began issuing citations to Lyft drivers, their large pink fur mustaches making them easy prey. Lyft was handed a temporary victory in early July when a federal judge overseeing the city’s lawsuit ruled that the company’s drivers could continue to operate until the matter is settled at trial.

While ride-share services may represent a very real threat to the city’s taxi companies, taxi drivers themselves often feel very differently about the public discussion and controversy Lyft has helped generate. In 2012 the Kansas City Taxi Cab Drivers Association, a group of over 200 area taxi drivers, filed a lawsuit in federal court against the municipal government of Kansas City in reaction to its taxi cab licensing practices. According to the lawsuit, the Kansas City government issues only a very small number of taxi cab licenses each year and exclusively grants them to just nine private companies. Under this system, independent drivers must lease a license from one of these companies in order to operate, all the while paying out of pocket to maintain their privately owned vehicles. The group of drivers claimed that the leasing fees, paid on a daily basis directly to the taxi companies, nearly eliminate their ability to earn a living and force many drivers to live below the poverty line. In the end the court sided with the city and the taxi licensing structure was kept in place. However, many of these same drivers must have been elated when Lyft landed in Kansas City in 2014 and at least temporarily made it possible for them to sidestep the current fee structure.

City officials of today maintain that ride-share services should be allowed to function so long as controlling companies and their drivers submit to appropriate regulation, a mandate that has effectively been used to eliminate transportation options for Kansas Citians on more than one occasion. Interestingly, language similar to that used in the past to disparage Kansas City streetcar interests has entered the arguments of Lyft supporters. In an opinion piece posted to The Kansas City Star website, Steve Rose has called for the breakup of the Kansas City taxicab monopoly. Rose reached out to Uber, another ride-share service based out of San Francisco, to ask when the company planned to enter the Kansas City market. Their response was not hopeful. At that time Uber was in no hurry to confront what they labeled as Kansas City’s entrenched and municipally protected taxi monopoly. Rose concludes his piece by stating that Kansas City should be encouraging new business models to grow and that the healthy competition brought about by these companies will only encourage taxicab providers to improve their level of service. Whether inspired by Rose’s urging or perhaps sensing that the climate for ride-share services in the city would soon change, Uber began operating in spectacular fashion in early May when Kansas City Chiefs running back sensation, Jamaal Charles, used the Uber app to arrange for a ride. City officials were reportedly “not amused” by the stunt.

The city council acted in early April, 2015, and with the support of Mayor James, passed a new ordinance that brings ride-share services under the same regulatory framework that governs the taxi industry in the city. Lyft officials, still hoping to reach a mutually beneficial arrangement with the city, were all but silent. Uber, on the other hand, spoke out immediately, declaring that the new regulations and fees may force them to abandon Kansas City entirely. It is true that ride-share services left to govern themselves may represent a very real threat to public safety. If this is the case, then the recent actions by the city council and the mayor will be regarded as just given time. However, if the goal of these new regulations is to insulate taxi companies from legitimate competition, as the jitney laws of the early twentieth century seem to have done for the financially strapped streetcar system, then how will their actions be remembered?

And how will the KC Streetcar project be received once it becomes fully operational in 2016? The answer to this question will depend largely upon whether the many misgivings of its critics are dispelled or confirmed over time. To many, it must seem that the city’s ride-share services, taxis, buses and streetcar system to come are headed for a confrontation. It is important, however, to remember that this fight is not one that will likely be taken up by average citizens. Much like their early 20th century counterparts, Kansas Citians of today are seeking the most affordable and convenient way to get where they need to go. Surely a greater number of options made available can only make it easier for each individual to find what works best. Rather, it will be for public officials and vested interests to fight over which option is outdated and which looks to the future, which represents a threat to the public and which is deemed safe. Time will tell which flourishes — and which may be legislated into extinction in Kansas City.