Brush Creek, a Kansas City Pipe Dream

Country Club Plaza, Brush Creek, Ambience on the Water, Wet Weather Solutions Program, Clean Water Act, Flooding, Boss Tom Pendergast, Ready-Mix Concrete, Battle of Westport

“I remember plugging my nose and sloshing up 47th Street,” says Kansas City-area resident Dennis Rich, “and seeing a Volkswagen stuck in a tree.”

In 1977, Rich woke up from a nap in the apartment building his godmother managed on Brush Creek in Kansas City, and heard his mother saying that she saw cars floating down the street on the Plaza. After a soggy summer, 16 inches of rain fell on Kansas City flooding the Country Club Plaza with six feet of water that killed 25 people and cost the city an excess of $66 million in property damages.

The Country Club Plaza reigns as Kansas City’s premiere tourism and shopping district. In the 1920s, architects Edward Buehler Delk and Edward Tanner designed the Plaza’s distinct Spanish colonial revival style architecture buildings. The Plaza’s appeal stems from over 100 shops that range from Armani Exchange and Michael Kors to the Apple store and MAC cosmetics and 50 restaurants that represent the world’s cuisines from Brazil to Japan and back again. With events such as WaterFire, Plaza Art Fair and the Plaza Lighting Ceremony, the district brings tourists and locals flocking like ducks to Brush Creek.

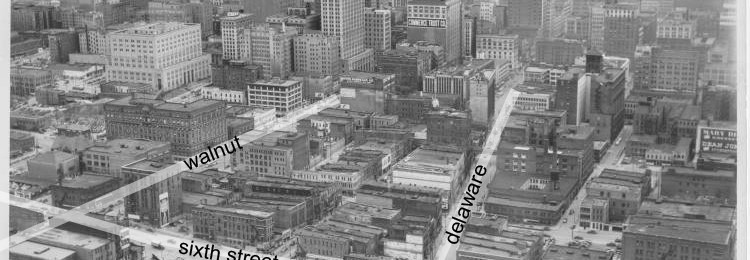

In 1935, City Boss Thomas Pendergast’s Ready-Mix Concrete Company laid concrete eight to 10 inches thick and 70 feet wide across the bottom of Brush Creek. The paving of Brush Creek—a 70 foot wide, 10.5-mile stream that spans three counties and runs through Kansas City’s Country Club Plaza—cost the city $1.5 million at the time, endangered over 40 species of fish ranging from golden redhorse, longear sunfish, northern hog sucker, to the Ozark minnow; and diminished the creek’s ability to replenish groundwater reserves.

Pendergast claimed at the time that paving Brush Creek would eliminate flooding. Following the ‘77 flooding, an additional flood occurred in 1993, resulting in a new flood control plan in 1999 that cost $1.3 billion. Kansas City’s 150-year-old combined sewer system—one that collects sewage and storm-water runoff in a single pipe system—and Pendergast’s concrete company, over 60 years, turned what was once a healthy creek into more of a polluted drainage ditch full of E.coli.

“For centuries,” states the Kansas River and Stream Corridor Management Guide, “humans have worked to control rivers and streams rather than attempting to understand and work with a stream’s natural tendencies.” The evidence is most obvious in urban areas where concrete-lined ditches, like Brush Creek, speed up storm water runoff that increases unhealthy floodwaters, and replaces natural stream channels.

In 2010, the Kansas Department of Health and Environment classified the segment of Brush Creek running through Mission Hills, Kans., just west of the Plaza, as a healthy stream designated for general purposes such as wading, fishing or boating. East of Mission Hills, when Brush Creek reaches Kansas City’s combined sewer district—a district that spans 56 square miles from State Line east to the Blue River and the Missouri River south to 85th Street—it is considered an unclassified body of water by the Missouri Department of Natural Resources, and therefore unprotected under the Clean Water Act—a program developed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in 1972 that would enforce all state and local water monitoring programs in order to promote higher standards of water quality for rivers, streams and lakes.

In 2010, the Missouri Coalition for the Environment filed a lawsuit against the EPA for not fully implementing the Clean Water Act in Missouri, namely for allowing so many streams to be unclassified. An unclassified body of water has no monitoring system and cannot receive provisions, which authorize federal financial assistance for municipal sewage treatment plants and repair.

Based on data collected from Kansas City, Mo.’s Water Services Department, levels of E.coli in Brush Creek exceed the standard levels enforced by the EPA by a factor of six. Consistent with the EPA’s recommendation for fresh-recreational waters, Missouri’s water-quality standard for water with any form of contact—such as riding on the Gondola boats that are for rent along Brush Creek on the Plaza—must contain less than 126 E. coli colonies per 100 milliliters of water. On August 28, 2007, Kansas City’s Water Services department measured levels of E. coli based on how many colony forming units existed per 100 milliliters of water (commonly known as CFU/100 ML). The raw sewage and waste-water overflows from our outdated sewer system contributes to the concentration of 780 E. coli colonies per 100 milliliters of Brush Creek water that flows along the Plaza—655 more units than the EPA’s standard for recreational waterbodies.

The air along Brush Creek holds the smell of sulphur dioxide—a chemical used in paper mills to soften the wood pulp and smells like fish guts, burnt matches and sewage. We are not in a town known for its paper production. We are in Kansas City, Mo., where sewage-warning signs line the Blue and Missouri Rivers, and Brush Creek, and state, “Streams receive combined sewer overflows. Avoid contact 72 hours after rainstorms.” The signs include stylized images of a human figure swimming, wading, and washing his hands in the water with bright red diagonal lines slicing over the figure. “In a typical year,” states the Kansas City, Mo., Overflow Control Plan issued on Jan. 30, 2009, “6.4-billion gallons of combined storm water and wastewater overflows untreated into Kansas City’s rivers and streams.”

Down the sloping sidewalk that leads to the creek from an eastern entrance across from Jack Stack Barbecue off of Ward Parkway, a sewage-warning sign— sponsored by Kansas City’s Wet Weather Solutions Program—cautions against any contact with the water. From April to November, however, during Kansas

City’s storm and rain season, Ambience on the Water, a company that provides gondola boat rides along Brush Creek on the Plaza, shuttles tourists and locals up and down a 1.5-mile stretch of the creek. “Ambience on the Water,” writes founder Chris Sperry, “is Kansas City’s newest five-star romantic destination.”

The boats sit along the edge of the creek next to one of several fountains that spray up from the water. Tourists and locals pay between $50 and $100 to take boat rides along Brush Creek choosing from a variety of packages that offer long-stemmed red roses, ice buckets of wine or Champagne, a box of assorted chocolates, cake, balloons, and two complimentary take-home wine glasses embossed with Ambience on the Water logos.

On cloudless days, the sun highlights the ripples on the creek like a school of piranha biting toward the surface. By noon, tall Bur Oaks and apartment buildings overshadow most of the creek’s pearl-tinted surface—blue, pink, purple or tan depending on how the sun lays or how fast the wind blows. You can see bubbles rise to the surface from the fish that can survive the conditions of the bacteria-laden water.

Across from the Intercontinental Hotel, at the intersection of Wornall Road and Ward Parkway and under the pedestrian bridge, you’ll find a large swath of shade. Here live the Plaza bats and graffiti half-painted over by city workers. “Do you care?” remains written in full, red capital letters on the ceiling of the underside of the bridge. From the gondolas you can see this pedestrian bridge lined with its swinging red lanterns. On the bridge, under the floating lanterns, Kansas City maintains one of its most notable photo opportunities: tourists face west, and the bobbing gondola boats and powerful jet sprays of the fountains accent the photo’s background. A polluted Brush Creek lays claim to picture frames, mantels and albums all over the country.

Near the west end of the Plaza, where Brush Creek turns into a tiered waterfall under Belleview Avenue, a ramp, where the gondola boats slide in and out of the water, collects Taco Bell-wrappers, Huggie’s diapers, Styrofoam cups, and a thick layer of creamy brown foam. You can see hordes of small bass buzzing under the pearl-colored film. The fish vibrate the surface of the water. Where the pruned sidewalks and landscaping end one can imagine how Meriwether Lewis and William Clark might have experienced Brush Creek in its original state, or how Major General Samuel R. Curtis and Major General Sterling Price and their soldiers experienced Brush Creek when they fought during the Battle of Westport—the largest battle fought west of the Mississippi River during the American Civil War. Artist N.C. Wyeth’s depiction of the Battle of Westport show soldiers standing on either side of Brush Creek, where waving prairie grasses surround the bright blue trail of water that made up Brush Creek in its original, unpolluted state.

Brush Creek dries to a foot-wide trickle at 50th and Ward Parkway. Large Bur Oak trees loom over the empty concrete that was once an earthen creek bed. Despite the overall declining state of its waterways, not all locals think that Brush Creek is a pipe dream. “I’m not afraid to say it,” local Jessica Burns says. “To me, the Plaza and Brush Creek are the most beautiful parts of our entire city.”